Economy + Geopolitics

December 2025

Almost the entire past month’s headlines were dominated by COP30, held from November 10–21 in Belém, Brazil, at the gateway to the Amazon rainforest. Ten years after the Paris Agreement, the world is exploring new ways to confront climate crises, which are increasingly visible in everyday life — as Hurricane Melissa recently demonstrated in Jamaica.

Yet the summit ended with a fire on the last day, Indigenous protests, and key absences from the U.S., leaving many critical issues misunderstood. The keyword to understand it all? Mutirão.

Why Mutirão?

Mutirão is a Portuguese word, originating from the Tupi-Guarani language, meaning “collective effort” or “joint action.” Traditionally, it refers to communities coming together to achieve a common goal, such as building, harvesting, or cleaning shared spaces.

By highlighting this Indigenous concept, COP30 signaled that solutions to climate challenges are increasingly sought from Indigenous knowledge. Holding the summit at the Amazon’s doorstep, engaging with local communities, and recognizing 10 new Indigenous territories underscored this focus.

Key Takeaways from COP30

The UN climate summit that concluded in Belém on November 22nd—exactly a decade after the Paris Agreement— will be remembered not for what it achieved, but for what it exposed. After three decades of climate negotiations, COP30 revealed how deeply fractured global consensus has become on addressing climate change, with nations leaving Brazil either vindicated or livid. The conference teetered on collapse when over 80 countries pushed for explicit language on transitioning away from fossil fuels, only to meet intractable opposition from major oil producers.

Yet amid this discord, COP30 managed to salvage meaningful progress. This was the first COP leveraged by the Global South, with Brazil and the BRICS nations at the helm, marking a significant power shift from the traditional Western-dominated climate multilateralism. This is reflected in the agreement to triple adaptation finance by 2035, which represents a landmark commitment to the world’s most vulnerable populations, those least responsible for climate change but most affected by its impacts. Furthermore, for the first time, trade policy entered climate negotiations in earnest, opening difficult but necessary conversations about carbon border taxes and economic fairness. The summit also launched a just transition mechanism and voluntary implementation accelerators designed to shift focus from endless negotiation toward tangible action.

The geopolitical landscape revealed deeper shifts beyond the negotiating rooms. The European Union, traditionally a climate leader, found itself cornered and weakened, unable to leverage its economic power effectively. Meanwhile, Russia—emboldened by Trump’s absence—actively blocked progress on fossil fuel roadmaps alongside predictable opposition from Saudi Arabia and other petrostates. China‘s strategy proved most revealing: while keeping a deliberately low political profile, it focused on dominating the practical reality of the green transition through its control of solar technology and clean energy markets, a long-term play that may prove more consequential than any negotiating text.

However, the real story may have unfolded in the margins. Against the backdrop of the Amazon, the summit elevated nature conservation and recognized Indigenous Peoples and local communities like never before, suggesting that solutions to our climate crisis might emerge not from air-conditioned negotiating halls, but from those who have protected forests for generations.

Reforesting the Minds

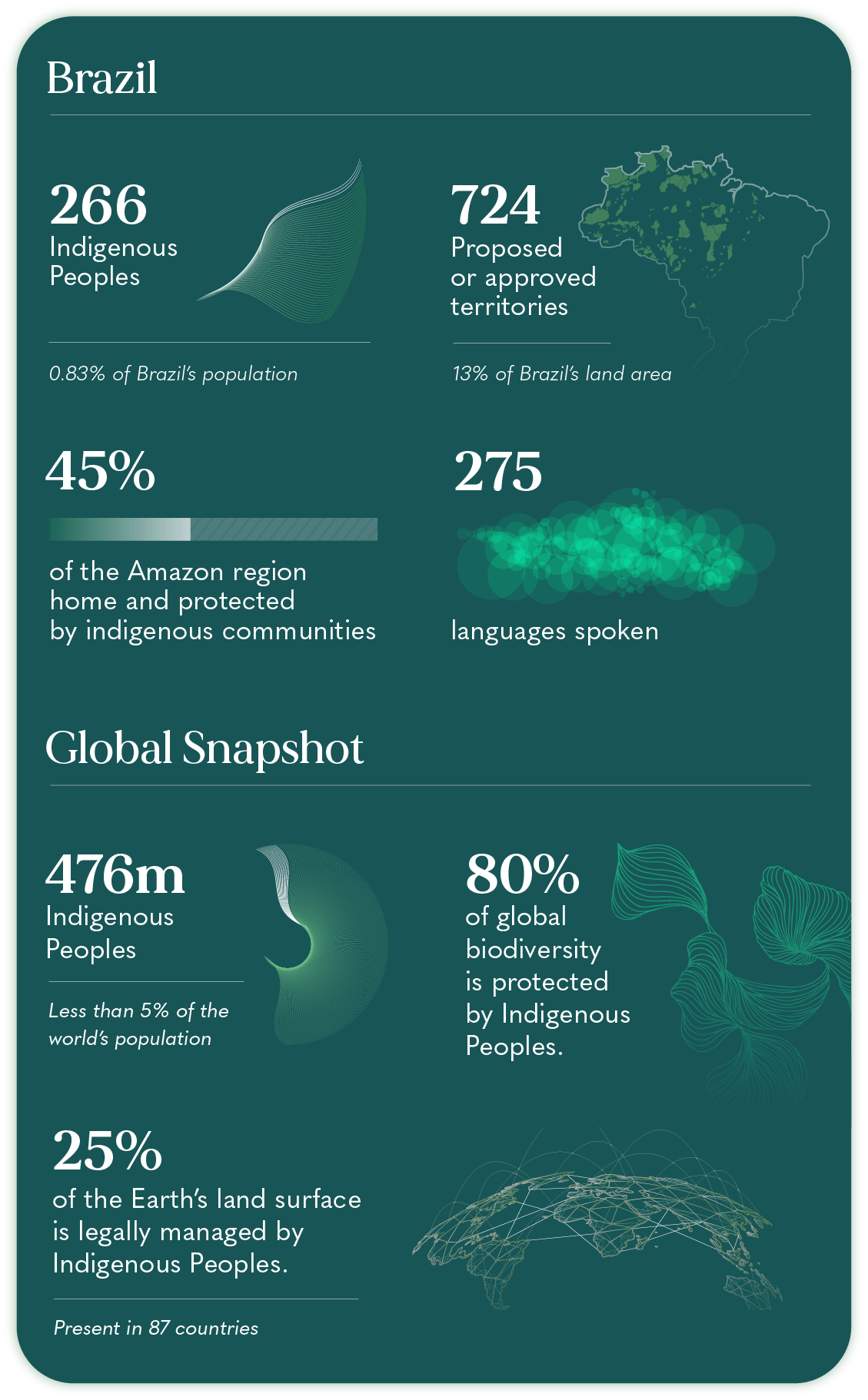

Perhaps the most profound shift at COP30 was the attempt to “reforest the minds”—a concept championed by Indigenous women that calls for seeing life beyond metrics and reports, recognizing the intrinsic connection between humanity and nature. Over 2,500 Indigenous people participated in what Brazil promised would be the most inclusive COP in history, the first held in the Amazon rainforest itself. The symbolism was deliberate: Brazil sought to demonstrate that those who protect 40% of the planet’s intact forests deserved a central role in climate governance. The Brazilian government incorporated Indigenous leaders into its national delegation and created the Peoples’ Circle, an advisory body designed to amplify their voices to the COP presidency.

The question was whether the international community would listen and the answer came swiftly: not really. While over 3,000 Indigenous delegates attended, only 360 secured passes to the Blue Zone negotiating spaces and inside those, Indigenous groups remained observers, unable to vote or attend closed-door meetings.

However, despite these frustrations, the Indigenous presence embodied COP30’s defining concept: mutirão, the Indigenous Brazilian Tupi-Guarani term for collective effort that appeared throughout the final agreement. In fact, Indigenous peoples represent the original mutirão—communities who have sustained forests, rivers, and biodiversity through generations of collective stewardship. Their traditional knowledge offers what negotiators desperately need: proof that another relationship with nature is possible. In fact, where Indigenous territorial rights are protected, deforestation plummets below rates in state-managed areas. That’s why recognizing indigenous rights and lands proves to be one of the most effective available strategies of climate mitigation.

The summit delivered concrete recognition of this reality. Brazil’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sonia Guajajara, announced ordinances establishing 10 new Indigenous lands, advancing demarcation processes that move them closer to full official recognition, while an additional 59 million hectares of public land were committed to Indigenous communities. Beyond these territorial gains, three COP documents explicitly acknowledged Indigenous rights, encompassing both land tenure and traditional knowledge. Complementing these measures, the launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility created a mechanism to financially support countries that keep forests standing, addressing a long-standing imbalance in forestry finance that has historically flowed mainly to areas already deforested.

These territorial recognitions came against a backdrop of mounting threats. Mining interests covet the critical minerals beneath Indigenous lands, essential for the renewable energy transition, while the Tapajós River remains contaminated with mercury from gold extraction. Brazil’s agribusiness-dominated Congress continues to push for further exploration, compounding the pressures on these territories.

In the face of such challenges, Guajajara’s message was unequivocal: countries must treat Indigenous land demarcation as climate policy itself, not a peripheral concern. The future of climate action may hinge less on negotiated texts than on whether the world can embrace the knowledge Indigenous peoples have preserved for generations: that protecting the Earth requires not only reforesting landscapes but also reforesting human consciousness.

What Does Indigenous Land Actually Mean?

To declare land as Indigenous is to fundamentally alter its legal and political status. In Brazil, where this question carries particular weight given that most of the Amazon lies within its borders, Indigenous land designation prohibits mining, blocks individual private property claims, and requires free, prior, and informed consent from Indigenous peoples for any activity affecting the territory. The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 defines these as lands traditionally occupied by Indians—territories they inhabit permanently, use for productive activities, and require for preserving environmental resources necessary for their well-being and cultural reproduction. It’s a definition that looks backward to recognize historical presence while guaranteeing forward into perpetuity.

Yet this constitutional protection, hard-won through decades of Indigenous organizing, remains perpetually contested. Brazil’s demarcation process is labyrinthine and politically fraught. After an Indigenous group submits evidence of traditional occupation, approvals must pass through the President of FUNAI (the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples), the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, and finally the President of Brazil himself. Then comes the most difficult part: removing non-Indigenous occupants and ensuring the land remains available to its rightful inhabitants—a process that can be long, violent, and incomplete.

Of Brazil’s 733 Indigenous territories, the government recognizes only 496, with 237 stuck at various stages of demarcation. Also, even officially recognized lands face constant threats: nearly 10% lack constitutional protections, suffering from overlapping claims, invasions, illegal mining, logging, and drug trafficking.

Their traditional knowledge offers the proof that another relationship with nature is possible. In fact, where Indigenous territorial rights are protected, deforestation plummets below rates in state-managed areas. That’s why recognizing indigenous rights and lands proves to be one of the most effective available strategies of climate mitigation.

A Global Patchwork

Indigenous land rights around the world form a patchwork of progress and denial, reflecting a spectrum of recognition that ranges from near-sovereignty to outright erasure. In parts of Latin America and Africa, legal protections have advanced measurably: countries like Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Panama, and Venezuela, alongside Burkina Faso, Tanzania, and Uganda, have established frameworks that often surpass wealthier nations. Laws such as the Philippines’ Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 recognize ownership of ancestral domains, while Ecuador’s 2023 referendum barred oil drilling and mining in Indigenous territories—a rare affirmation of territorial sovereignty. Even in the Nordic countries, Sámi Parliaments offer advisory oversight, though their authority remains largely consultative rather than sovereign.

Elsewhere, recognition is largely symbolic. Canada enshrines Aboriginal and treaty rights in its Constitution, and New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi protects the Māori, yet enforceability depends on statutory interpretation. In India, the creation of a Ministry of Tribal Affairs and the 2022 election of Droupadi Murmu, a tribal leader, signal inclusion—but not full power.

The picture is most striking in the Middle East, where governments from Iraq to Saudi Arabia deny Indigenous communities meaningful land rights, asserting state ownership of virtually all non-private territory. For nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples, this erasure disrupts seasonal migration, livelihoods, and cultural continuity, threatening centuries of stewardship.

Amid this fractured landscape, one truth stands out: Indigenous land is not a single concept but a continuum, and the 476 million Indigenous people worldwide—just 6% of humanity—protect roughly 80% of global biodiversity. Their stewardship consistently produces lower deforestation rates and improved access to health, education, and sustainable development. By recognizing land demarcation as climate policy itself, COP30 signals what evidence has long shown: the planet’s future depends less on new technology than on whether the world chooses to protect those who have always known how to protect the Earth—and the knowledge and practices that make it possible.

Language as Climate Technology

The most radical dimension of Indigenous climate stewardship may be the least visible and still the most endangered: language itself. For example, of approximately 1,200 Indigenous languages spoken in Brazil when Europeans arrived, only 274 survive today. Each extinction erases what Altaci Corrêa Rubim calls “inventories of species, classification systems, etiological narratives and, above all, ways of managing diversity”—a fundamental technology for environmental preservation that exists nowhere else. These languages encode generations of ecological knowledge: which plants heal, when to plant, how species interact, how to read changing weather patterns.

Thus the connection between language and land protection forms an indivisible survival strategy. Indigenous worldviews embedded in language position humans as part of nature rather than separate from it, creating the philosophical foundation for practices that have sustained biodiversity for millennia. When communities are displaced from ancestral territories—whether by force, economic pressure, or climate impacts—the linguistic transmission breaks. Urban migration fragments the contexts where words retain meaning. Children lose fluency. With the language goes the knowledge of how the forest breathes, which streams hold medicine, where the animals move with the seasons. What UNESCO now calls the Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-2032) recognizes an urgent truth: language loss accelerates ecosystem collapse because the instructions for their preservation die with the words.

The Hidden Loss

4 Patterns Linking Languages and Vanishing Landscapes

Glaciers are melting, forests are burning, and the reality is clear: climate change is already here. But another loss unfolds quietly beside the environmental one—languages tied to these disappearing landscapes are vanishing too. Over the past year, through Global Perspectives, we’ve traced four key patterns linking ecological collapse and cultural erosion, from Peru to Greenland. Here’s what the world is losing, and why.

Discover it hereWhat André Corrêa do Lago envisioned as “science and ancestral knowledge walking side by side” requires recognizing that Indigenous languages are themselves climate infrastructure. The 274 languages still spoken in Brazil, the countless others across the globe, contain specialized knowledge about different biomes developed through intimate, sustained relationships with place. Language sovereignty—the right to preserve, develop, and control one’s language—proves inseparable from territorial sovereignty. Both are prerequisites for self-determination, and both are essential technologies for survival.

The question COP30 posed but couldn’t answer is whether humanity will protect these linguistic repositories before the climate crisis silences them forever, taking with them humanity’s accumulated wisdom about how to live on a planet it has nearly destroyed.

The World After Belém

COP30 ends not with tidy resolution but with a narrative break—a moment when the old storyline of climate diplomacy finally faltered, and another, still unwritten, began to press forward. What Belém exposed is that the world can no longer rely on incremental negotiations staged far from the realities they claim to address.

In the Amazon, it became impossible to ignore that the most enduring climate strategies are already alive in Indigenous territories, in languages that hold ecological memory, in communities that have practiced mutirão for centuries. Closing COP30, then, is not an ending but an invitation—to abandon the illusion that technical agreements alone can save us, and to embrace a deeper transformation rooted in responsibility, justice, and the courage to imagine another way of living with the Earth.

Sources: Nature Sustainability, Mongabay, World Resource Institute, Context, The Nature Conservancy, UNESCO, Scielo Brasil, LSE, The Conversation, Bloomberg, IWGIA, PBS News, COP30, Cultural Survival, BBC, Le Monde, Nature, BBC, COP30