Trends

How speaking more languages can generate more value: Imminent’s Research Director explores the strategic role of multilingualism in the age of digital and multicultural information. Multi-awarded author and journalist Luca de Biase is a professor at Pisa University, innovation editor at Sole 24Ore newspaper and a Member of the Mission Assembly for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities, amongst many other roles and achievements.

What is the value of being able to express oneself in every language? To what extent can the ability to do so change our understanding of the needs of others, our capacity to explain our own proposals, our chances of reaching an agreement that creates total mutual trust? How is all this changing in the world of digital globalisation, considering the progress of artificial intelligence and the platform economy?

Imminent is Translated’s research centre. Using facts regarding the economy of international relations as a starting point, it aims to develop a vision of how intercultural communication can evolve. Of course, the possible scenarios of the future are not foretold: they are a consequence of what we do, based on what we imagine and describe. In all languages.

“The possible scenarios of the future are not foretold: they are a consequence of what we do, based on what we imagine and describe”

An awareness of languages is an integral part of any respectful and open-minded approach to intercultural relations. Any international project can be improved if it has a way to express itself in the languages with which it seeks genuine contact. But in this era of sweeping transformation, everything is changing; these principles are evolving, driven by the great modern-day engines of change. The quality of international communication can be facilitated or hindered by the evolution of the global platform, which allows messages to travel from one language and one culture to another.

Imminent Annual Report 2021

Fit your business in global shape. Get your copy of Imminent Annual Research Report 2021. And let us know what you think.

Get your copy now

The year the world sped up by hitting the brakes

The past year will leave its mark. The great pandemic of 2020 has disrupted health systems and economies around the world. Many countries have decided to restrict or suspend activity in order to slow the rate of infection. This has accelerated certain organisational change processes, drastically increasing the use of digital platforms for an enormous range of economic, social and cultural activities. We have adopted solutions that we had previously failed to see, even though they were right before our eyes. The paradigm of resilience has replaced the paradigm of efficiency, and the limit of what is possible has shifted. When normality does return, it won’t be normality as we know it.

In the new paradigm, innovators are called upon to go the extra mile. To think ‘beyond’ their proposals. To think about the systemic consequences. To think about what changes and what must last. From work to consumption and from education to information, digital technology makes certain routine activities more productive. Conversely, however, its mass adoption only serves to highlight the richness of moments of serendipity, creativity, the birth of new social relationships. A new form of planning is making headway, one with greater awareness of the symbiotic relationship between the physical and the digital; it seeks out opportunities in a hybrid environment that combines digital automation and cultural quality. A tension is emerging: digital strives for quick and simple operations, while culture demands depth and diversity; digital explores the value of things that can be codified, while culture nurtures the value that stems from understanding complexity.

“A tension is emerging: digital strives for quick and simple operations, while culture demands depth and diversity”

Well, in the knowledge economy, in the context of globalisation, value is exchanged on physical-digital platforms, but it is generated by exploring diversity and takes shape through mutual understanding. Innovation does not exist until it is recognised and adopted. At an international level, this implies a shared understanding of its meaning in different cultural contexts. There can be no development without a complex system of enabling infrastructures. In the age of digital and multicultural information, the strategic role of the language services ecosystem is emerging as one of these infrastructures thanks to its ability to facilitate intercultural relationships.

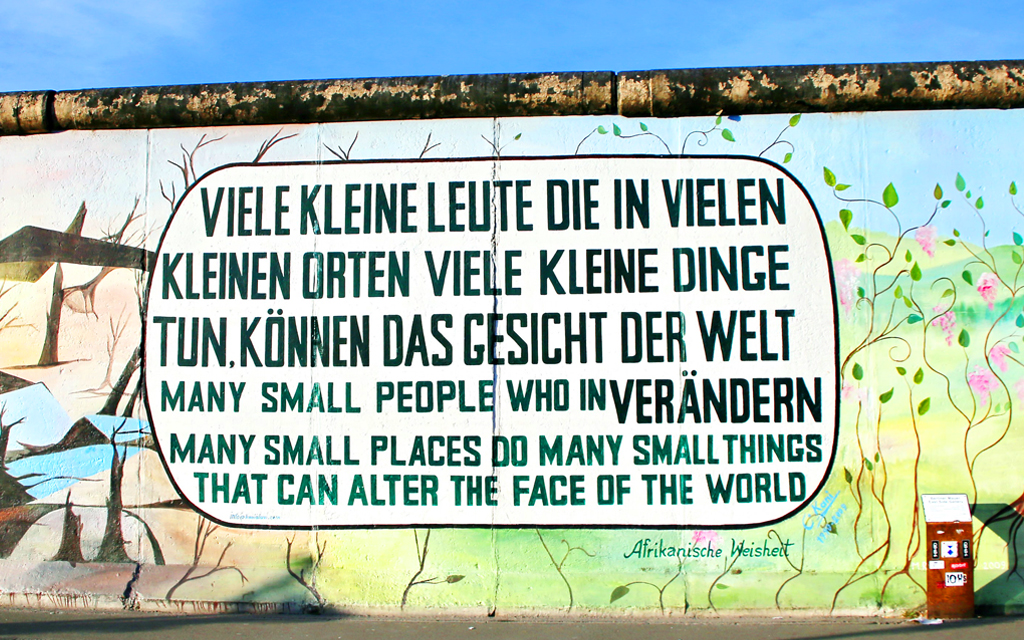

‘The Wealth of Nations’ is the part that everyone remembers from the title of the book by Adam Smith, which contributed to the foundation of the traditional economy and described the first steps of industrialisation. This title can be evoked to mark the dawn of a new phase in economic history. In Smith’s time and in the industrial economy, value was generated by promoting the international division of labour. In today’s knowledge economy, however, it is generated by sharing value between cultures: ‘the wealth of languages’.

Imminent Annual Report 2021

Fit your business in global shape. Get your copy of Imminent Annual Research Report 2021. And let us know what you think.

Get your copy nowAll of this has implications for the economy, politics, technology and culture. Language service platforms increase the capabilities of humans, but they also direct them by defining part of the limit of what is possible. They are at the centre of some of the most significant dynamics responsible for ensuring harmony, but they also feed conflict; they enhance the quality of local life in connection with the global dimension. And the number of problematic frontiers is growing. We are witnessing an increasing focus on the main languages, but also a re-assessment of local languages. Global platforms (and their preferred languages) are overwhelmingly powerful, but this paradoxically increases the political and economic power of minor languages. We speculate about possible consolidation in the language services market, but at the same time there is an increasingly robust distributed architecture in the platforms that transmit the meaning of messages from one culture to another thanks to a symbiotic collaboration between technology and professional expertise.

“‘The wealth of languages’ is not a stable fortune, but a wealth in the making”

‘The wealth of languages’ is not a stable fortune, but a wealth in the making. And its image is not static but dynamic. Its sophisticated value cannot be glimpsed in any single product, but in the proliferation of communication possibilities that it offers. Questions abound: how much is investment in localization worth? How do we evaluate the quality of it? Where does its technology lead? To what extent does it respond to the market, and to what extent does it change it?

Small data and big emerging issues

When strategic tensions emerge in the deep-lying structures of intercultural relations, this is highlighted by certain events. And indeed, over the course of 2020, we have witnessed adjustment phenomena in the geo-economy of languages: the relationship between multilingualism and linguistic homogeneity; the potential impact of what happens in less widely used languages; the encounter between an evolutionary dynamic oriented towards consolidation and the maintenance of a distributed structure in the language services market. All these phenomena lie on the boundary between technological innovation and the professional evolution of the humans who work in language services. And they point to a surprising outlook for 2021 and beyond.

1. The vitality of multilingualism

Are we moving towards a consolidated focus on a handful of languages or a re-emergence of multilingualism?

When Ursula von der Leyen delivered her State of the Union address to the European Parliament on 16 September 2020, she broke with tradition. She spoke in French for almost four minutes in two sections at the beginning and end of the speech. She used German for nine and a half minutes halfway through her speech. And she spoke in English for an hour and three minutes overall.

The balance of languages in the Parliament was disrupted. Von der Leyen chose English as the pragmatic language of her office; her use of the other traditional languages of the Commission was purely a matter of common courtesy. Yet after Brexit, out of 751 members of the European Parliament, there are only around twenty native English speakers according to the calculations of Tim King (Politico). Jean-Luc Laffineur, president of the association GEM+, which promotes multilingualism in European institutions, commented on the matter in La Libre Belgique, noting that English is the mother tongue of 1.5% of the EU’s population, while only 10% of EU citizens speak it at a very high level. This is confirmed by Michele Gazzola in an article for Imminent.

The problem is practical rather than theoretical. The increasingly widespread use of Global Practical English could only be considered an inevitable trend if no better alternatives reveal themselves. However, the latter could well happen given the improvement in the quality of machine translation. Moreover, just as the President of the Commission was choosing one path, the European Parliament continued to demonstrate a very different sensibility, one in favour of multilingualism. By way of example, the Parliament has acquired automated technology to provide simultaneous translations of its members’ speeches in all languages. One of the suppliers is Translated, the company that founded Imminent.

“It so happens that European Commission officials, whatever their first language, have been led to produce texts exclusively in English for the last twenty years or so. They are de facto employed as first-level translators despite not being such”

Observatoire Européen du Plurilinguisme

As the Observatoire Européen du Plurilinguisme writes: ‘It so happens that European Commission officials, whatever their first language, have been led to produce texts exclusively in English for the last twenty years or so. They are de facto employed as first-level translators despite not being such.’ It is also conceivable that this practice of linguistic reduction to non-native English is one facet of the notorious lack of empathy found in the Commission’s speeches: empathic communication is easier in one’s own language. Machine translation could perhaps modify this procedure by allowing the Commission’s officials, as well as Members of Parliament, to speak and write in their own language without hindering the circulation of texts within departments and at various hierarchical levels. Automation and the richness of linguistic diversity are not at odds – quite the opposite, in fact. In reality, humans cognitively augmented by machines can be the champions of a major drive to promote the world’s linguistic heritage.

What’s more, in the linguistic geopolitics of a multipolar world, we can no longer take anything for granted. For example, it is not necessarily true that education systems are always geared towards teaching the most common languages. Until August 2020, the Ministry of Education in India recommended that five foreign languages be given priority for teaching in schools: French, German, Spanish, Chinese and Japanese. Since August, Chinese is no longer on the list. Meanwhile, the ministry has been monitoring the sources of funding for Chinese schools in India. These moves are part of the cultural and economic conflict that now separates India and China. This conflict also includes a hundred Chinese apps that have been banned in India, as well as the termination of contracts with Chinese companies that handled major infrastructures.

Imminent Annual Report 2021

Fit your business in global shape. Get your copy of Imminent Annual Research Report 2021. And let us know what you think.

Get your copy nowMeanwhile, China has diluted the importance of English in its secondary school foreign language teaching. In June 2020, the Ministry of Education decided to change its programmes by adding German, French and Spanish to the languages taught up to that point (English, Japanese and Russian). All schools are expected to teach at least two foreign languages. French is also included as one of the optional subjects for the university entrance exam (GaoKao). The government believes that this will create a generation of Sino-French goodwill ambassadors. In a speech given at the Daming Palace in Xi’an during his state visit in 2018, President Emmanuel Macron addressed Chinese students learning French, saying: ‘You have made the right choice. Knowing French will be an advantage in your future.’ The fact is that English remains the priority: it has replaced Russian in most Chinese courses of study, is studied by 400 million Chinese pupils, and plays an essential part in the GaoKao. However, the way English is learned in China is focused primarily on reading and less so on listening and speaking skills.

The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, produced in 1996 by around a hundred NGOs with input from the UN and UNESCO, guarantees the fundamental legitimacy of everything that can help develop a multilingual approach for human communities. It also includes a series of principles relating to the media and to what were then ‘new technologies’, reiterated and explored in greater depth in a 2003 recommendation (Promotion and Use of Multilingualism and Universal Access to Cyberspace). At the time, those principles perhaps seemed right to support but impossible to implement. However, with the advent of machine translation and the power of platforms that allow humans – augmented by machines – to collaborate in developing intercultural and multilingual communication, the principles of the Declaration have suddenly proved actionable.

“Complexity will prevail over simplification in the future of languages”

In reality, it can be assumed that complexity will prevail over simplification in the future of languages. Consider that after many decades of English being taught in European schools, only an estimated 10% of the population is fluent in the language. Consider also that after a lengthy period of British colonial rule, India continued to invest in the teaching of English after it gained independence; according to the last census, however, only 10% of the population speaks English. All this indicates that there are very powerful social, cultural and economic reasons for maintaining traditional languages. Moreover, national languages are defended from a political standpoint against linguistic ‘colonisation’, and this phenomenon does not seem destined to let up.

The pragmatic dynamic that leads Global English to conquer spaces in politics or science is therefore at least as strong as the dynamics that nourish the vitality of local languages. If we imagine that the future will not be very different from the past in this regard, precisely because of the structural sluggishness of cultural change, the problem of intercultural communication will not be solved by simply assuming that linguistic diversity will diminish in favour of the languages that hold political or economic power. Thanks to the improvement of language services augmented by automation and the support of increasingly powerful digital tools with voice interfaces, in an environment dominated by digital media communication, we may approach the point at which Umberto Eco’s idea becomes a reality and ‘the universal language is translation’.

Observatoire Européen du Plurilinguisme

2. The impact of minorities

Do we use translations to speak or to listen?

Accused of all kinds of evildoing for his wait-and-see approach to the falsehoods published on Facebook during the American presidential election campaign; interrogated by the European and American authorities for the spread of hate speech on his platforms; singled out for the massacre of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar: Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has had a tough 2020 in terms of public relations.

Among the various crises he has faced, the one involving the Rohingya is particularly instructive. Facebook reacted too slowly in Myanmar because it did not have humans or machines capable of understanding messages written in Burmese: the platform monitors for hate speech in 40 languages, according to information released in late 2019. Facebook claimed to have removed 7 million posts containing hate speech in the third quarter of 2019, up 59% from the previous quarter. There was then a drop in the fourth quarter of 2019, but the increase was emphatic in 2020, with 9.6 million posts reported or removed in the first quarter and 22.5 million in the second quarter. Facebook employs 35,000 people to combat toxic communication and, according to a report by Time, these posts are identified with the aid of artificial intelligence in 80% of cases. This system, which checks posts written in a limited number of languages, introduces a bias: the automated fight against hate gives free rein to users who speak languages other than the most common ones. As a result, a lot of content – an enormous amount, in fact – evades the monitoring process.

And this problem is not limited to relatively small countries. Africa’s largest country in terms of population, Nigeria, was hit by a series of rather unusual public order and disinformation problems in the autumn of 2020. One of the police force units that operates in the country is heavily criticised. Known as the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), it is accused of having become a corrupt and violent organisation. The New York Times reported that a peaceful demonstration against the SARS was met with shooting by the police, resulting in several deaths. This turned the demonstration into something much more violent, with looting and vandalism. Amnesty International has documented various cases of torture and violence by the SARS. The founder of the police unit itself told the BBC that the SARS had become a criminal organisation. The non-violent protests stemmed from a video that the police denounced as fake. The brutality that arose from it, however, was anything but. The protest movement organised itself on social networks using the name #endSARS.

On Global Voices, a network of free bloggers founded in Boston to give a voice to people writing from all over the world, Nwachukwu Egbunike wrote that Facebook flagged news referring to #endSARS as fake and aided the government as it tried in every way possible to hide the problem of the SARS, the protests, and the violence suffered by the demonstrators. Facebook uses outsourced staff for fact-checking. In Nigeria, it uses Africa Check, AFP-Hub and Dubawa. As far as we understand, the languages that these organisations monitor are Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa, while the protests also involved people who speak Ohaneze Ndigbo, Ijaw and Itsekiri. In the midst of the protests, Instagram admitted that it had blocked certain posts in error, believing that they contained fake news. It’s not the first time. Two weeks earlier, Facebook found itself embroiled in a controversy over the spread of hate speech in India. A couple of years earlier, it was accused of spreading fake news by Brazil’s largest newspaper.

In 2016, Facebook removed a post purely because it criticised the Singapore government. In 2011, Facebook shut down the account of a blogger who had published a series of posts on crime in Honduras. And in 2010, Facebook shut down the ‘We are all Khaled Said’ page, which discussed how the 28-year-old Egyptian was beaten to death by police in Alexandria. Facebook’s methods run the risk of censoring human rights activists, or at least of making mistakes that disadvantage them. ‘It has happened many times, often without an explanation from the American company’, says Ellery Roberts Biddle, a journalist, technology expert, and Editorial Director of Ranking Digital Rights, interviewed via email by Nwachukwu Egbunike for Global Voices.

Across the Western world, there are questions about how to contain what the World Health Organization calls an infodemic of fake news and hateful opinions. Often, we rely on platforms that (like Facebook) can automatically intercept many toxic posts and remove them or at least limit their spread. But this method is not sufficient, because the risk is that Facebook and other platforms, for a quiet life or for other reasons, will fail to distinguish between the manipulation of hatred for sinister political ends and the genuine protests of people criticising those in power. The future of social media and public debate depends on how this problem is resolved.

A little later than common sense would dictate, Mark Zuckerberg has realised that hate is ‘language-specific’. But he still has a long way to go. Over the course of 2020, he was targeted by a very powerful alliance of advertisers who had no intention of investing in a platform where ads could end up on pages that glorify violence and hatred. After a complex discussion, the parties came to an agreement on 23 September. There will now be standardised definitions and processes for hate speech on the main platforms (Facebook, YouTube, Twitter), and independent authorities and third parties will be brought into play to help develop suitable controls against the spread of online hate speech. Presumably, this collection of third parties will begin to include partners who offer language services in order to classify the containment of toxic messages and expand monitoring to less widely used languages.

We can generalise from this experience. When an intercultural communication system makes the decision to focus the translation and localisation of services exclusively on the world’s main languages – a reasonable choice given the costs of translation – the conditions are put in place for problems to arise in the languages that remain untranslated. Although these problems concern linguistic minorities, they can be enormously significant for global systems such as large international platforms. The case of Facebook is only the most sensational to emerge last year. Those who operate in ecommerce, have international service platforms, or work to connect people online will find themselves in a similar situation sooner or later. During 2020, online communication platforms – partly in light of the tensions caused by the heated American presidential election campaign – took on the responsibility of checking the information that they circulate in order to prevent it from becoming too toxic or dangerous for the public.

One could imagine, therefore, that the age of these platforms avoiding responsibility is over and that a new era is upon us, one based on their commitment to guaranteeing the quality of the information that they circulate. And there is no reason to think that this will not apply to all digital platforms. They will need to localise their services with respect for local attitudes; they will have to abide by the diverse rules of different nations; they will have to learn to use their tools to read what their users say and do.

This, however, means emphasising a sometimes undervalued aspect of language services: we use them not only to say what we want to say in other languages, but also to listen to what those who speak in other languages are saying. This can be an important factor in the safety of the services offered, in a company’s image, in learning something about the cultures the company deals with, in localising in a way that is more respectful of others, and certainly in improving mutual trust in commercial relationships. This has the potential to open up a major new chapter in the evolution of language services, motivated by the fact that communicating is not just about sending messages, but also about receiving them.

3. Consolidation in language services

Is consolidation inevitable in the language services industry?

Typically, consolidation in a sector occurs because it is a mature industry, due to financial and speculative opportunities, or finally due to the network effect caused by the intrinsic logic of technology. The world of language services does show a certain tendency towards consolidation, but the sector’s distributed architecture is also proving to be very resistant – something which could demonstrate the permanently irreplaceable role of the human contribution to language service provision. The theory is that trust in the result of language services is an integral part of the work; humans develop this in a more engaging way than machines can, thus network technologies do not work as stated in Metcalfe’s Law and consolidation due to the network effect does not prevail. And certain problems that have arisen during 2020 suggest not only that this will continue to be true in the future, but also that it will become even more important.

“Trust in the result of language services is an integral part of the work”

Let’s take a look at what happened. In 2020, RWS bought SDL in a share swap for more than a billion dollars. Two of the world’s top five translation companies by turnover merged. What does this move mean? Does it indicate a trend towards consolidation in the language services market? Consolidation is a typical trend in mature markets, but the language services market cannot be described as such: innovation is powerful, there are huge opportunities for a large number of players, and the market is growing. According to Nimdzi, the global market for language services will reach 55 billion (USD) in 2020 despite the lockdown, and it will continue to grow over the following years, reaching 66.7 billion in 2024. However, the market remains decentralised: according to Nimdzi, the top 100 companies account for only 14.5% of global business, and the top 150 companies account for 20.1% of the total.

But not all companies are the same. The two aforementioned companies that merged are among the few near the top of the rankings that are listed on the stock exchange and have access to significant capital. In fact, the acquisition was made by means of a share swap: RWS was able to buy SDL by giving its own shares to SDL’s shareholders. In a context where investment in technology is a must, access to financial capital can become an important variable. At the end of 2019, the Poland-based LSP Summa Linguae made another relatively important acquisition. Other previous major acquisitions have failed, such as the planned merger between Lionbridge and TransPerfect in 2017. But a strategy of growth through acquisition is one thing, due in part to the shareholder structure of the companies doing the buying, with the presence of private equity and financial strategies often playing a role. Organic growth is another thing entirely. Consolidation due to technology should occur independently of acquisitions.

Together, RWS and SDL are likely set to be the top-ranked companies in the sector in 2021 – at least judging by the positions they held in the 2020 ranking published by Slator – and will go on to offer services across all the vertical sectors of the language services industry with the highest growth. This is the most important growth event of the year, and it occurred due to an acquisition permitted by the shareholder structure of the companies involved. Until the sector demonstrates sufficient maturity to cause consolidation, therefore, we only see the phenomenon in relation to companies driven in this direction for reasons that are technically financial. But are we also seeing consolidation due to technology?

Machine translation has in fact made further strides in terms of efficiency and quality. There has been a lot of talk in the sector this year about the potential contribution to translation of GPT-3, an artificial intelligence designed to produce high-quality texts. In 2020, this technology caused a stir not only for its undoubted power, but also and above all because of the choice of messaging around its launch. Its promoters initially declared that they could not release it because it was too dangerous given what it could become if it fell into the wrong hands, in a context in which disinformation and other forms of misleading communication influence the quality of global information. As a result, when it was actually released, GPT-3 received the sort of attention rarely afforded to this kind of technology. The impression generated by GPT-3’s products, however, must be kept within the limits of human common sense, because this is precisely what the technology lacks.

In general, technology has generated operational consolidation but not economic concentration. According to some estimates, with the advent of Google Translate, 99% percent of the translations performed around the world are carried out by an automatic platform. However, 99% of the translation industry’s turnover is generated by companies that offer the work of professional translators, aided to a greater or lesser extent by machine translation technology. And since the industry’s overall turnover is growing, as we have seen, this means that consolidation due to technology is not going unchallenged.

“99% percent of the translations performed around the world are carried out by an automatic platform. However, 99% of the translation industry’s turnover is generated by companies that offer the work of professional translators”

Under these conditions, can we imagine that investments in translation technology could lead the market to a situation of organic consolidation based on the network effect that favours the most widely used machine translation platforms? With the current figures, there is still a long way to go. For now, consolidation seems to be taking place more through acquisitions than through technology. One possible explanation is the fact that the distributed architecture of the market is still linked to the perceived – and demonstrable – quality of the services and therefore to ways of gaining customer trust. What are the consequences of technology in a sector that remains so fragmented? Can we declare that the fate of this industry will be similar to that of newspaper publishing? In that case, the sum of the turnover of all newspapers was almost double that of Google as late as 2015, but today Google brings in one and a half times the turnover of all the newspapers in the world put together.

If the language services industry evolves quickly in a way that finds a balance between technology and human added value, can it avoid ending up in this situation? In other words, without giving Google a monopoly over technological innovation and without debasing itself, instead nurturing the value and quality of the professional contribution made by humans to its production structure? On the other hand, machine translation was not created yesterday; given that it has not yet led to drastic organic consolidation, it may be that the distributed architecture has very strong reasons to resist this.

These reasons could be further reinforced in the future. One phenomenon that is not as widely studied as it should be concerns the quality of the data used to train artificial intelligence for translation. It is hard to forget that this quality depends on the work of humans. One current trend, however, actually seems destined to further emphasise this circumstance. The increasing use of large data sets to improve artificial intelligence creates a risk that these sets could be manipulated or contaminated by criminals intent on blackmailing companies or worsening their chances of operating on the global market, or by foreign powers interested in complicating the international relations of their adversaries.

Imminent Annual Report 2021

Fit your business in global shape. Get your copy of Imminent Annual Research Report 2021. And let us know what you think.

Get your copy nowAccording to an investigation by the Wall Street Journal, some of the world’s top cybersecurity experts are starting to notice the risk of attacks on the databases used for artificial intelligence. For Elham Tabassi, Chief of Staff in the Information Technology Laboratory at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, if we fail to keep an eye on the sources of the data fed into artificial intelligences, we leave the door open for hackers or criminals who can take advantage of the algorithms and automations used by companies and other organisations. This ‘data poisoning’ is a growing practice. If the attackers have an idea of how algorithms work and understand how the data fed into the machines is selected, they can contaminate it in order to generate behaviour that furthers their aims, notes Tim Bandos, Chief Information Security Officer at the security company Digital Guardian, Inc.

“If we fail to keep an eye on the sources of the data fed into artificial intelligences, we leave the door open for hackers or criminals who can take advantage of the algorithms and automations used by companies”

Elham Tabassi, Chief of Staff – Information Technology Laboratory at the National Institute of Standards and Technology

All this must also apply to machine translation. The only way to be sure that the data is valid is to have humans in control of what is happening: cybersecurity experts, but also linguists and translators, of course. If machines are trained in an environment controlled by humans and with data generated by humans, as is likely in all situations where automatically generated data is lacking, this drastically reduces the probability of a successful cyberattack such as those mentioned above on machine translation systems.

Trend detection and possible adjustments

With all these tensions, the balanced solution for the progress of language services lies in symbiotic work between humans and machines.

The tensions that we observe lie in opposition to one another: multilingualism vs homogenisation centred around a few languages; consolidation in the language services market on the basis of acquisitions for financial reasons or the network effect of large tech platforms vs the continued existence of the distributed architecture in the structure of this market; innovations in technology vs innovations in business models.

1. In a sector that is growing both technologically and culturally, the hypothesis is that there is value to be explored in two directions: in the volume of translations (speed and quantity of words transferred from one language to another) and in the quality of translations (multilingual creative copy, transcreation, creative translation, depth of meanings transferred from one cultural context to another). In the world of digital communication, this balance between the two tensions is fundamental; without speed and quality, the system loses value.

2. Increased multilingualism and the ‘dumbing down’ effect of Global English: those who thought that the automation of translations could impoverish the world’s linguistic heritage might have to change their mind, given that automation seems to be fairly effective in counteracting the concentration of communication in a Global English that is highly practical but of poor quality.

3. In the participatory logic characteristic of life on modern digital media, the techno-human platform of language services tends to expand its value both in the direction of those who need to transmit a message into a linguistic context other than the original one, and in the opposite direction – towards those who need to listen to what is being said. Translating to say something to someone who speaks another language, but also to listen to what someone is saying in another language. All this must be understood within the framework defined by the great engines of change.

But the innovations do not stop there. Digitisation continues to generate changes that are sometimes surprising, partly because the context is constantly changing.

The great structural engines of change form the evolutionary backdrop for every scenario concerned with interpreting the future prospects of the modern world. Digitisation, globalisation, climate change, social polarisation, demographic growth in the global south and an ageing population in the north: these are all fundamental trends that influence every economic and cultural activity and most likely mark out our path to the future.

In addition to these structural trends, there are also powerful economic phenomena: the divorce between finance and the real economy in the markets, information pollution in the media, the geopolitics of political cyberwarfare, and the resurgence of localism in urban planning, to name just a few that are particularly significant for international relations.

“Progress today is at a crossroads between the burgeoning possibilities generated by technological innovation and the responsibility of choices guided by leadership”

In this context, the essential change is probably the end of a forty-year period founded on the technocratic belief that letting technology and finance do the work is the route to the best possible approximation of progress, replaced instead by the advent of a phase in which leadership steers innovation. In short, progress today is at a crossroads between the burgeoning possibilities generated by technological innovation and the responsibility of choices guided by leadership that interprets the zeitgeist and offers reasons to decide where our priorities lie. From this point of view, Europe – which had its general elections a couple of years before the US – is further ahead in articulating a vision of innovation fit to respond to the 2020 crisis, although it is obviously further behind in terms of the innovation ecosystem. The vision defined at a European level is focused on the objective of simultaneously improving the sustainability, equity, productivity and macroeconomic stability of European societies.

The novelty of this vision compared to the lack of ambition in previous decades lies precisely in the belief that we can steer innovation and think of it as the way to improve the quality of the environment, fight social injustice, qualify the value of culture, and simultaneously generate wealth and stability. All these measures are designed to respond to the immediate crisis, but with maximum focus on the long-term consequences. 2020, for reasons that no one would have wanted to see, can become a turning point for the direction of innovation.

All this causes a major cultural earthquake that has consequences for every frontier of innovation, including the world of language services: a world whose bread and butter is frontiers, not only for the obvious reason that the industry facilitates international relations, but also because it responds to the growing demand for translation and localisation on the basis of highly sophisticated organisational and technological development.

Indeed, the international dimension of developed economies continues to grow, and with it the demand for translations. The OECD estimates that 40% of jobs in German companies are supported by purchases made by foreign consumers, but the percentage is also high elsewhere: it hits 30% in Italy, slightly less in the UK and France, 25% in Canada, just over 15% in Japan and just over 10% in the USA. Obviously, this is an increasingly frequent occurrence thanks to the mediation of digital tools. The language services system must respond to this growing demand with speed and quality. Practically every future trend in the world of language services is driven by the relationship between technology and professional expertise. The biggest problem and the biggest opportunity in this world lies in the symbiosis between the design of machine translation tools and the evolution of the professional quality of humans.

Imminent Annual Report 2021

Fit your business in global shape. Get your copy of Imminent Annual Research Report 2021. And let us know what you think.

Get your copy nowIn this context, certain trends have been clear for some time. We can divide them into trends that concern the demand for language services, and those that concern the supply and application of said services.

According to many observers, demand is increasingly focused on video subtitles and dubbing, localisation of services designed for voice interfaces, and translations to ensure the compliance of online activities with new legal developments. Increasing consideration is also required for the following: local habits when it comes to marketing and ecommerce communications; the availability of translations not only in the most widely spoken languages but also in the languages of emerging market economies; efficient services for the mass localisation of international service platforms.

In terms of supply, the following have been the focus of development for some time: machine translation of texts with efficient ‘human-in-the-loop’ editing to reduce turnaround times with the same costs and quality; machine translation for multilingual audio; an increasing number of machine-translatable languages; improved translator quality for more sophisticated tasks (copy, transcultural communication, transcreation, creative translation); synchronisation of translation services with the most dynamic needs of international platforms.

New applications of language services, as already noted, concern translation operations for increasing volumes of content; translations of texts for technical support, produced to be fed into machines that need to be trained with data; eLearning applications; synchronous business chat; creatively localised advertising and promotion and other forms of creative translation; and an increasing use of translations for services related to global health needs.

We will probably also have to develop a low-cost translation solution for all the professionals who work from home and are looking for clients around the world. Self-employed people who work from home are not necessarily destined to stay local. Translation services today are already founded on precisely these kinds of self-employed workers, who serve a global market; there is no reason why they cannot enable other workers in different sectors to seek a place in global markets.

The translation of communication between machines could also be a theme in the evolution of the industry: the implementation of digital twins may lead to the need for them to communicate internationally and to consume defined data in all kinds of languages. Communication between large databases may no longer be limited exclusively to those in the languages of the major platforms, but also in the languages of users and the new platforms that will arise in the future. International relations between systems of services for citizens, which have proved important in the event of a pandemic, could lead to more intense interlinguistic exchanges, with artificial intelligence using linguistic domain bases extended to multiple languages. The list goes on.

Sooner or later, we will emerge from lockdown. But certain phenomena that emerged or picked up speed during the lockdown will not fade away easily. The pandemic was a challenge to everything that could once be taken for granted. Social distancing; contact monitoring; a new focus on viral dynamics that raised awareness of how networks function; the structural reorganisation of health systems; new habits in transport, catering and public services: all this will have a lasting impact. We also need to consider emerging preferences for solutions that were previously only possible but which were thoroughly tested during the lockdown and suddenly became normal: sometimes attractive, often efficient and convenient, but also trivialising, mentally and psychologically tiring, and altogether disorienting.

“The digital dimension will play a bigger role in our reorganised daily lives and we must redesign its physical substance in order to ensure a future of high-quality development”

We emerge with the sense that the digital dimension will play a bigger role in our reorganised daily lives and that we must redesign its physical substance in order to ensure a future of high-quality development. The use of large digital platforms for communication and commerce has become much more widespread, demonstrating the enormous opportunities on offer and at the same time the limits to the depth of the experience, something that has yet to be overcome. The collection of colossal amounts of data and the significance of the artificial intelligence necessary to exploit this data are two sides of a coin that has grown exponentially.

There is an emerging need for a new social infrastructure based on enabling platforms that strike a balance between the increased opportunity to automate certain cognitive activities and the growth of our human ability to redesign, reform, define and enrich the meaning of activities that interpret complexity, overcoming the current trivialising effect of technology and incorporating into the process a true convergence of the physical and the digital. Physicality has taken back responsibility for guaranteeing resilience in the logistics of proximity, while digitisation has become the main avenue for exploring global opportunities. The multiple dimensions of the phygital and the glocal have defeated the one-dimensional nature of the flat digital and global world and the poverty of the local and analogue world.

In this context, the system of language services that enable intercultural relations clearly takes on a strategic, proactive and (potentially) increasingly central role.

Imminent Annual Report 2021

Fit your business in global shape. Get your copy of Imminent Annual Research Report 2021. And let us know what you think.

Get your copy nowThe translation and localisation industry can seize these opportunities by explicitly taking on the identity and organisation of a sort of techno-human platform with a distributed architecture: a network of people and technologies endowed with special and unique knowledge that has far-reaching consequences, enabling multilingual, intercultural, international and global communication. Within this system, artificial intelligence grows at the speed of the data that enhances the efficiency of machine translation systems; at the same time, the professional expertise of the humans involved in the process is developed and enriched with increasingly sophisticated functions. It makes no sense to imagine a purely technological platform developing in opposition and as an alternative to our human capacity for work, but rather a truly symbiotic organisation that is increasingly powerful; one of the most magnificent demonstrations of collective intelligence.

If this is true, a distributed architecture system with relatively widespread technological innovation, accelerated professional growth and growing demand could be a candidate to play a proactive role in the world trade system, because it adds quality to relationships, challenges marketing habits, helps to adapt messages to different cultures, and invites us to transform product and service innovation into meaningful innovation. All without losing its pragmatic spirit of service and its speed of action. The consequences of this theory are as yet unwritten.

One fact, however, is certain. In the next few years we will witness the definitive battle between emerging capitalism – what the World Economic Forum calls ‘stakeholder capitalism’ – on the one hand, and the capitalism of the digital exploitation of the labour force fragmented and organised by dehumanising platforms on the other. The collective intelligence of language services can become the proof that platforms are not necessarily condemned to be on the side of these dehumanising forces; on the contrary, in the case of translations, the platform is defined precisely by the value of the humans who bring it to life. For these platforms, the goal is trust rather than attention. Machines are not organised to control humans; instead, humans are asked to correct and guide machines. Production is not focused solely on quantity with no regard for quality.

Stakeholder capitalism, in which companies are designed to have a valuable social impact, needs high-tech examples that do not fall prey to platform consolidation and the fragmentation of labour. Language services can be this example, as they experience accelerated technological progress with a distributed architecture and the growing professionalisation of the humans who drive them. The result is a hypothesis that can be generalised: machines are perfect for carrying out all codifiable tasks, while humans are better at generating value by interpreting complexity.

In short, the responsibility of the language services system will increase moving forward. The projects that will be discussed over the course of 2021 will range from the participatory multilingual platform for European democracy to the creation of methods to ensure the transparency of the artificial intelligence involved in translations, so as not to allow prejudices and biases to influence the result. The paradigm shift that language services are called upon to make is the result of technological and professional progress and of a context that makes the demand for this increasingly clear: they are shifting from the transfer of words from one language to another to the transmission of meanings from one cultural context to another. Meanwhile, there is an evolving demand for multilingual communication platforms used not only to speak but also to listen. Finally, localisation services are evolving and learning to respect different cultures.

Rather than predicting 2021, we need to design it.

Five laws of the language service of the future

“The relationship between humans and machines is symbiotic rather than parasitic”

There is therefore a global platform for language services that is not owned by anyone but is made up of a number of companies, institutions, people, machines, associations, and so on. A true collective intelligence that forms the eco-cultural niche for the progress of all development dynamics that require strong intercultural relationships. The form of this collective intelligence – if you want to choose from those put forward by Tom Malone, founder of the Center for Collective Intelligence at MIT – is an ecosystem that develops around an inextricable and inseparable set of platforms, algorithms, databases, technical expertise and humanistic skills which co-evolve by adapting to change, generating and anticipating innovation.

A collective intelligence that functions as an ecosystem evolves through the mutations of its ‘inhabitants’ with regard to the overall resources it can use, thanks to continuously changing connections that allow it to lock on to other forms of activity. Each element coevolves with every other, but we can recognise certain regularities:

- Cognitive diversity is an enabler of the complexity management system (multilingualism is a value that is useful for the health of the ecosystem, not a duty to be imposed on the ecosystem)

- Respect between the cultural components guides communication methods and enables the quality of the platform

- The relationship between humans and machines is symbiotic rather than parasitic

- Trust is an exceptionally important resource in a context where the product speaks on behalf of customers but is incomprehensible to them; this begets a preference for proximity to the supplier and therefore for a distributed market architecture rather than one focused on the most widely used technology

- The evolution of the digital environment, from digital twins to the standardisation of data quality systems, places a growing strategic focus on the demand for high-quality, high-speed translations with strong strategic expertise.

These are empirical observations rather than laws. In the world of language services, those who are able to verify how realistic they are ahead of time and interpret the consequences may be able to gain an advantage over their competitors. But above all, they will always be able to create new applications for their services by generating products capable of bringing innovation to their customers’ operations in line with the growing strategic role of intercultural communication.

Photo credits: Jacqueline Brandwayn, Unsplash / Clem Onojeghuo, Unsplash / Radu Mihai, Unsplash /

Rory Carson, Unsplash / Mark Konig, Unsplash / Jonne Huotari, Unsplash / Marianna Villanue, Unsplash