Global Perspectives

September 2024

Key Statistics

- The most competitive economy in the world.

- Singapore is the 5th in the world for GDP (in USD) per capita.

- The world’s 4th largest exporter of high-technology products.

- Ranked 2nd in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index.

- Ranked 2nd on a list of 113 countries globally and 1st in Asia out of 23 countries for English proficiency.

Lah, Lor, and Beyond

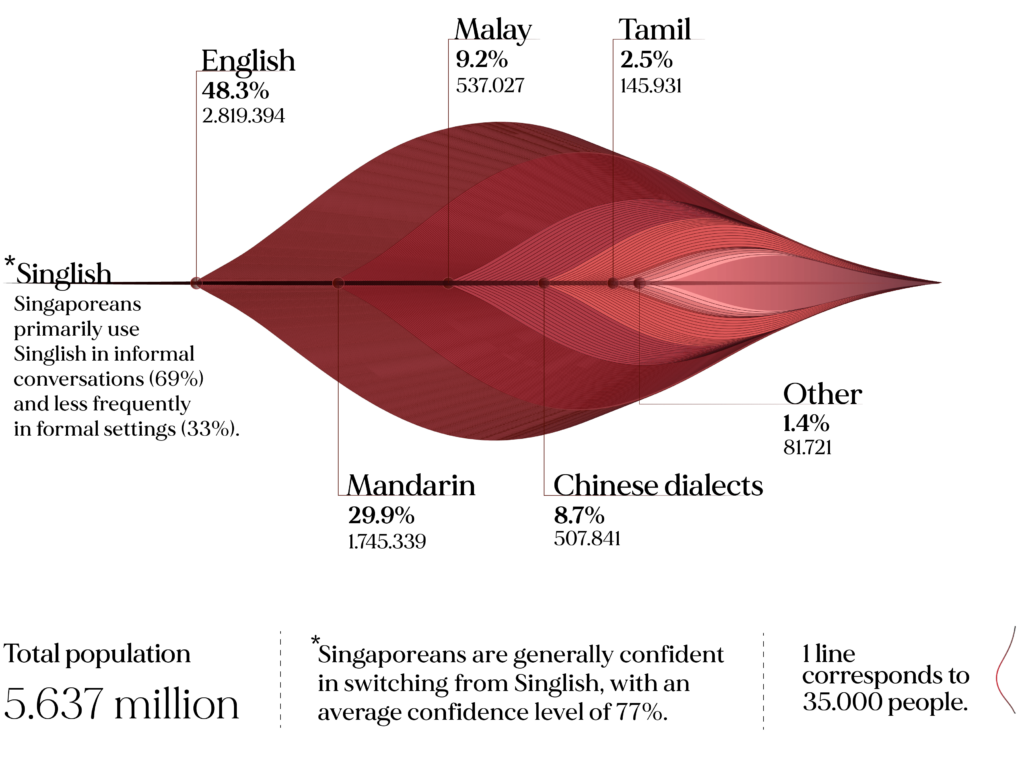

In the vibrant and multicultural tapestry of Singapore, language serves as both a bridge and a boundary, reflecting the island nation’s colonial history and rich diversity. As a historical crossroads of trade, Singapore has long attracted people from various parts of Asia, including China, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia, creating a unique blend of cultures and languages. When the British established their colony in 1824, English became the administrative and educational language, while Mandarin Chinese, Malay, and Tamil were promoted to preserve ethnic identities and foster social harmony. Today, these four languages coexist officially, mirroring Singapore’s complex identity and history. Recent statistics show that English is spoken at home by 48.3% of the population, Mandarin by 29.9%, Malay by 9.2%, and Tamil by 2.5% (Wikipedia).

A key element in Singapore’s linguistic landscape is its bilingual education policy, which was established after World War II and strengthened in the 1960s. Under this policy, students are taught English as the primary language while also learning their designated “mother tongue”—Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil. This policy was implemented to ensure that, while English served as the common language for economic and administrative purposes, ethnic languages would be preserved, fostering social cohesion and cultural continuity. The success of this policy is evident, with 74.3% of the population now literate in two or more languages (Department of Statistics Singapore), underscoring Singapore’s commitment to maintaining a multilingual society.

In this context of linguistic diversity, Singlish—a colloquial, hybrid variant of English—emerged as a distinctive linguistic phenomenon. Unlike a typical pidgin that develops for trade, Singlish evolved from the English spoken in schools, adapted by students who spoke other languages at home. This created a version of English that, while not quite “proper,” was functional and resonated with the cultural identities of its speakers. Singlish incorporates elements from Malay, Hokkien, Tamil, and Cantonese, making it a dynamic and living language that reflects the multicultural experiences of Singaporeans. It is widely spoken in everyday life, from casual conversations to local media, embodying the pragmatism and adaptability of Singapore’s society.

Source: Department of Statistics Singapore

Singlish, however, is not a monolith. It varies greatly depending on the context and the speakers involved, ranging from a language closely aligned with standard English to one that is almost entirely its own. Phonetic features like equal stress on syllables, dropped consonants, and altered sounds contribute to its distinctiveness. Common phrases in Singlish, such as “like that” becoming “liddat,” and the use of loanwords like kiasu (fear of losing out) and shiok (very good) add layers of meaning that are deeply rooted in local culture.

Perhaps the most iconic element of Singlish is the use of pragmatic particles—words like lah, lor, and meh—which are often borrowed from Chinese dialects and must be spoken with the correct tone to convey the intended meaning. These particles, much like verbal emojis, add nuance to conversations, expressing resignation, confirmation, completion, or objection. The meaning of the particle lah, for instance, can change depending on the tone used, adding a rich layer of expression that standard English cannot replicate. Many Singaporeans view it as a vital part of their national identity, a linguistic marker that sets them apart from other English speakers.

However, the Singaporean government has long viewed Singlish as a potential impediment to economic progress and global communication. In 1999, the then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong emphasized the need for standard English to keep Singapore competitive, leading to the launch of the Speak Good English Movement (SGEM) in 2000. The SGEM aims to promote grammatically correct English, ensuring that Singaporeans can communicate effectively in a globalized economy. The government’s concerns are not without merit. Singlish’s fluidity means that speakers often slide between it and standard English, sometimes without realizing that their speech may be difficult for others to understand. Critics argue that schools should focus more on teaching standard English, as the ability to communicate clearly and correctly is seen as crucial for Singapore’s image and business environment.

Singlish incorporates elements from Malay, Hokkien, Tamil, and Cantonese, making it a dynamic and living language that reflects the multicultural experiences of Singaporeans.

Nevertheless, Singlish persists, thriving in the face of official disapproval. An anonymous counter-movement, the Speak Good Singlish Movement (SGSM), emerged in 2010, advocating for the preservation of Singlish as an integral part of Singapore’s cultural heritage. This movement underscores the idea that Singlish complements rather than hinders the learning of standard English, providing a bridge between formal and informal communication.

The cultural significance of Singlish has even gained international recognition. The inclusion of Singlish terms in the Oxford English Dictionary and the success of local Singlish films on the global stage highlight its importance. For many Singaporeans, Singlish is more than just a dialect; it is a symbol of national pride and unity, reflecting the resilience and creativity of the Singaporean people. A 2024 survey by the American online language learning platform Preply found that 95% of Singaporeans use Singlish slang “in some capacity” (Preply).

In its coexistence with standard English, Singlish illustrates the dynamic interplay between globalization and local identity in Singapore. The government’s promotion of standard English is driven by practical concerns, but the enduring popularity of Singlish highlights its deep-rooted connection to national identity. Amid the tension between modernity and tradition, Singlish stands as a living example of how languages evolve and develop.

Kampung Society

Beneath Singapore’s modern metropolis lies the enduring essence of kampung culture, a philosophy deeply rooted in the nation’s past. The word “kampung,” meaning “village” in Malay, represents more than just a physical space; it embodies a way of life characterized by neighborliness, mutual aid, and communal harmony. In the traditional kampung, residents looked out for one another, shared resources, and came together during celebrations and hardships. This spirit emphasized simple pleasures, a connection with nature, and living in the moment. Today, even as kampungs have been replaced by high-rise apartments, the kampung spirit continues to thrive, as reflected in various aspects of Singaporean life and the city itself. The intrinsic values of community and mutual support remain ever-present, balancing the drive for innovation with a deep-rooted commitment to social cohesion. This balance is crucial in a society as multicultural as Singapore’s, where diversity is celebrated as a strength, not viewed as a challenge.

The word “kampung,” meaning “village” in Malay, represents more than just a physical space; it embodies a way of life characterized by neighborliness, mutual aid, and communal harmony.

The vibrant multiculturalism of Singapore is vividly displayed in its distinct neighborhoods, where each community retains its cultural identity while contributing to the broader national fabric. Towering above the city’s rich tapestry of culture stands the Jamae Mosque (Chulia), a striking green structure that embodies the peaceful coexistence of different religions within Singapore’s diverse society. Chinatown dazzles during the Lunar New Year with its array of Chinese tea shops, silk garments, and traditional medicines, while Little India comes alive during Deepavali with lights adorning the streets, traditional Indian attire, and herbs and spices. Kampong Gelam, one of Singapore’s oldest urban districts, with its iconic Sultan Mosque and the diverse community it serves, stands as a testament to the city’s harmonious blend of cultures.

Hawker centers, designated as UNESCO heritage sites in 2020, are another living example of this spirit. These communal dining spaces offer a melting pot of cuisines from Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Western traditions, serving as gathering places where people from all walks of life share meals and conversations, transcending ethnic boundaries. These hawker centers are microcosms of Singapore’s multicultural ethos, promoting social interaction and community bonding through food.

As such, the essence of kampung spirit intertwines seamlessly with Singapore’s pragmatic approach to economic growth, where a focus on profit margins and market strategies dominates educational curricula, preparing students for a competitive future. However, the intrinsic values of community and mutual support—hallmarks of kampung life— remain ever-present, balancing the drive for innovation with a deep-rooted commitment to social cohesion.

In fact, the Singaporean government actively nurtures this multicultural reality through various initiatives. The Housing Development Board’s Ethnic Integration Policy ensures a balanced ethnic mix in public housing estates, preventing ethnic enclaves and encouraging daily interaction among different groups. Racial Harmony Day, commemorating the 1964 race riots between Chinese and Malay groups, reinforces the importance of social cohesion through educational activities that promote respect and understanding. Legislative measures like the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act and the Presidential Council for Minority Rights further support this commitment to a harmonious society. Singapore’s model of multiculturalism is not a melting pot where cultural identities fuse into a dominant norm, but rather a mosaic, where each ethnic group is encouraged to preserve its unique culture and traditions while appreciating those of others. In Singapore, each ethnicity is encouraged to preserve its culture and traditions while appreciating those of others, fostering a richer, more inclusive national identity.

Singapore’s model of multiculturalism is not a melting pot where cultural identities fuse into a dominant norm, but rather a mosaic, where each ethnic group is encouraged to preserve its unique culture and traditions while appreciating those of others.

Digital initiatives also play a significant role in promoting this multicultural kampung spirit in modern society. The SGKampung app, developed with support from the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth’s Our Singapore Fund, aims to rekindle community ties through digital means. The app facilitates neighborly interactions, allowing users to offer and request help, loan or sell items, and organize social activities. By leveraging technology, the app helps sustain the kampung spirit, encouraging a supportive and connected community that transcends the physical limitations of modern urban life.

Singapore

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!City in a Garden

Singapore’s urban development is a captivating tale of how visionary ambition and strategic innovation have shaped the state into a “City in a Garden.” This transformation, beginning in 1965 with the bold vision of Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, has seen the city-state evolve from a small trading port to a leading global metropolis, where green spaces and advanced technology coexist harmoniously.

The story of urban planning in Singapore began almost 60 years ago. On September 12, 1965, shortly after Singapore had been cast out of the recently formed Federation of Malaya and subsequently declared its own independence, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew stood before a crowd of town hall supporters and proclaimed, “We made this country from nothing, from mudflats! Ten years from now, this will be a metropolis. Never fear!” Today, Singapore is a gleaming city of the future, a global financial center framed by lush greenery at every turn. Its skyline features a dizzying array of designs by the likes of I. M. Pei, Kenzo Tange, Paul Rudolph, Zaha Hadid, and many others.

The city’s public infrastructure, comprising a comprehensive transportation network, an excellent education system, and superb roads, serves a population of about 5.8 million within a landmass of barely 720 square kilometers. Singapore’s transformation has been achieved through long-term planning, a necessity given its small size and island confines. Every square meter matters, leading to a focus on building high-rises to save space, carefully balancing the functions of buildings, incorporating abundant greenery, creating more land through reclamation, and ensuring sufficient housing.

The impressive public housing system is a cornerstone of Singapore’s urban planning success. Specifically, the Housing and Development Board (HDB), established in 1960, played a crucial role in this transformation by developing new towns and public housing estates. In fact, by the 1980s, over 80% of Singaporeans lived in HDB flats (National Library Board), which were innovative in their use of prefabricated components, high-density yet livable communities, and public amenities such as schools, parks, and community centers. The government’s ownership of land and development of housing has ensured a supply of affordable accommodation, with more than 90% of Singaporeans owning their homes (Statista). This model provides financial security and a sense of belonging, contributing to the city’s high quality of life.

Source: The World of Teoalida

Furthermore, Singapore’s advanced application of technology has significantly improved its citizens’ quality of life. The city-state is well known for its high living standards, excellent public infrastructure, world-class education system, and efficient access to information and communication technologies. Singapore’s investment in transportation, healthcare, public safety, business development, and energy has facilitated its development as a smart city. Its advanced public transportation system, including the extensive MRT network, uses smart ticketing systems and innovative technologies like automatic train control and intelligent signaling. The city is also exploring the use of autonomous vehicles and drones to further enhance transportation. Technology is used extensively in many different fields: the healthcare system benefits from telemedicine, improving access to care; the Smart Nation App provides citizens with access to a wide range of government services; and initiatives like the Data Innovation Programme Office and Corppass facilitate business interactions and cybersecurity. Meanwhile, education initiatives, such as the TechSkills Accelerator program, are preparing citizens for a digital-ready future.

On the other hand, Singapore’s use of technology is perfectly integrated with green initiatives, earning it recognition as a “Garden City.” This commitment to sustainability is exemplified by its efforts to become the world’s greenest city, with over 40% of the country covered in green spaces (SG101). The Singapore Green Plan 2030 aims to further expand these efforts, adding new parks and increasing tree planting. The concept of biophilia, defined by naturalist E. O. Wilson, as humanity’s innate desire to affiliate with other forms of life, permeates Singapore’s urban design. Iconic green spaces like the Gardens by the Bay showcase the city’s commitment to integrating nature into urban life. This vision was championed by Lee Kuan Yew, known as the “Chief Gardener,” who initiated an annual tree-planting day in 1971. This commitment to green urban design not only enhances the city’s aesthetic appeal but also provides environmental benefits like pollution reduction and temperature regulation. The commitment to energy efficiency is evident in its green building initiatives, with a goal for 80% of buildings to be green by 2030. The Marina Bay Sands complex is a notable example of this effort. Waste management is another area where Singapore excels, with initiatives like the National Recycling Program and the Tuas South Incineration Plant, which converts waste into electricity.

The Fourth Tiger

In the pantheon of modern economic miracles, Singapore’s ascent stands as a testament to the power of vision, strategic governance, and the relentless pursuit of progress. From its humble beginnings as a small, resource-scarce island at the crossroads of trade routes, Singapore emerged in record time as the fourth “Asian Tiger,” joining Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan in a league that symbolized unprecedented growth and industrialization in the latter half of the 20th century.

Singapore’s rise is often cited as the epitome of successful economic development, a case study that continues to inspire policymakers and economists alike. At the heart of this transformation was the foresight of its founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who, in the wake of Singapore’s forced separation from Malaysia in 1965, recognized that its survival would depend not on natural resources, which the country lacked, but on human capital and strategic positioning. The government embarked on an ambitious plan, laying the foundation for an economic model that would turn Singapore into a global hub for trade, finance, and innovation.

In just a few decades, Singapore’s GDP per capita soared, surpassing many developed nations, and its economy diversified into high-value industries such as electronics, pharmaceuticals, and financial services. The government’s proactive role in nurturing these sectors, through state-directed investments and the creation of a conducive business environment, was instrumental. In fact, Singapore’s success was not merely the product of free-market dynamics, but rather a symbiotic relationship between state intervention and market forces. This unique blend allowed Singapore to attract substantial foreign investment while fostering an ecosystem where local enterprises could thrive.

Source: Worldbank

However, the backbone of Singapore’s economic fortune has always been its people. With a population built on a mosaic of immigrants, Singapore’s strength lies in its diversity. The government’s emphasis on education and skills training transformed a fledgling workforce into one of the most competent and adaptable in the world. In turn, this made Singapore an attractive destination for multinational corporations seeking a stable and skilled base in Asia. Moreover, the city-state’s openness to global talent ensured a continuous influx of expertise, further bolstering its competitive edge. For Singapore, people are its most valuable resource, and the country has capitalized on this to an extraordinary degree.

The backbone of Singapore’s economic fortune has always been its people. With a population built on a mosaic of immigrants, Singapore’s strength lies in its diversity. The government’s emphasis on education and skills training transformed a fledgling workforce into one of the most competent and adaptable in the world.

Yet this success has not come without its challenges. Rapid economic growth has led to a sharp increase in the cost of living, making Singapore the most expensive city in the world (The Economic Times). This has sparked concerns, particularly among expatriates, who are increasingly seeking more affordable alternatives elsewhere in Asia. The exodus of expats could potentially strain Singapore’s talent pool, especially in critical industries that rely heavily on international expertise.

Compounding these issues is Singapore’s demographic challenge. The population is aging, and with one of the lowest birth rates in the world, the natural replacement of its workforce is not assured. This demographic shift poses a significant risk to the sustainability of Singapore’s economic model. As the population ages, the pressure on social services and healthcare will intensify, potentially leading to higher taxes and further exacerbating the cost of living.

Despite these looming challenges, Singapore’s economic resilience remains formidable. The government continues to innovate, exploring new sectors like green technology and digital finance to maintain its competitive edge. Moreover, there is a growing emphasis on creating a more inclusive society, with policies aimed at addressing income inequality and ensuring that the benefits of growth are widely shared.