Global Perspectives

A Life of Respect

[…]

On maps of the country

We must draw points and lines

to show we have been here –

and are here today,

here where the foxes run

and birds nest

and the fish spawn

*

You circumscribe everything

demand that we prove

We exist,

that We use the land that was always ours,

that We have a right to our ancestral lands

*

And now it is We who ask:

By what right are You here?

Ataqqeqatigiittut

[…]

Nuna assiliorpaat

uanngaanniit uunga titarlugu

aana killissaa

aana ilissi aana uagut

Tuttut uaniipput

aaku timmissat

aamma aaku aalisakkat

*

Suna tamaat killormut pivaat

uagutsinnullu uppernarsaqqullugu

apeqquserlugulu

ilumut inuusugut

nunalu tummaarigipput

*

Ataqqeqatigiittut aaku kisimik

uagut uumasullu.

Aqqaluk Lynge (born 1947, Aasiaat, Greenland) is a Kalaaleq leader and poet dedicated to Indigenous rights. As president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (1995–2002) and a member of the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, he has been a key advocate for Inuit self-determination. A founder of the Greenlandic party Inuit Ataqatigiit, Lynge’s influence extends through his poetry and essays, published in multiple languages, which explore identity, resilience, and Arctic realities.

From Colonial Shadows to Self Determination

“We do not want to be Americans, nor Danes – we are Greenlanders.” These were the words of Greenland’s Prime Minister, Mute Egede, following renewed discussions from the newly elected U.S. president about his interest—first expressed in 2019—in purchasing Greenland. Though the consequences of this attention remain uncertain, the mere idea that someone could seek to “acquire” Greenland—undermining the hard-fought yet still partial autonomy of its 55,800 inhabitants (Worldometers, 2025)—is prompting both Greenland and Denmark to rethink their complex and often fraught relationship. In fact, these declarations, though part of a broader political rhetoric, have drawn international attention, giving the remote Arctic island a platform to voice its deepest desire: full independence.

Greenland’s colonial history dates back more than 300 years and has often been portrayed as an example of “peaceful colonization”—one supposedly carried out in the interest of the colonized rather than for the benefit of the colonizers. Danish colonialism in Greenland has been described as “neocolonialism” or even “colonialism by peace”—since no military force was used, economic power prevailed through the Royal Greenlandic Trading Company, and settlers did not interfere with the traditional lives of Greenlandic hunters. However, historical studies of the colonial and postcolonial periods have shed light on numerous contradictions, calling into question the supposed benefits of Danish rule.

In 1953, Greenland officially ceased to be a colony, becoming a province of Denmark. However, rather than gaining autonomy, it remained politically, economically, intellectually, and geographically governed by Denmark and its dependence on the former colonial power grew even stronger. As a result, a policy of “Danization” was implemented: a “modernization” of Greenland following the Danish model, driven by urbanization and state-funded education, carried out largely by a Danish workforce. This process, motivated by administrative and economic interests, had a profound impact on the island’s population. Today, 88.9% of Greenland’s 57,000 inhabitants belong to Indigenous Inuit groups (Statista, 2022), making the country the second-highest in the world in terms of Indigenous population percentage. These communities have long maintained a lifestyle deeply connected to the island’s natural environment, relying on traditional economic activities such as hunting and fishing.

From the 1960s onward, a wave of Danish laborers arrived in Greenland to construct modern housing, bringing carpenters, architects, and urban planners who enjoyed significant privileges, including higher salaries and free housing. As these new buildings replaced traditional turf houses, Greenlanders moved into urban centers, particularly around the capital, Nuuk, and many remote villages were shut down to concentrate development. This rapid pace of modernization was striking—what took centuries in Denmark unfolded in just a few decades in Greenland. Alongside the urban transformation, which introduced new infrastructure and housing, the economy also modernized swiftly, particularly through the industrialization of fishing.

Culturally and linguistically, Danish influence was equally overwhelming. Until 1979, Danish was the primary language of government, culture, and education. Additionally, from 1950 to 2000, many Greenlandic children were sent to Denmark for schooling, only to return as professionals trained under the Danish model. This practice shaped countless disrupted lives, leaving individuals struggling to identify with either culture fully.

This profound cultural and social upheaval has had devastating consequences for Greenlanders, who now face one of the highest suicide rates in the world. While the global average is around 9 suicides per 100,000 people, Greenland’s rate stands at 80—and in 1989, it peaked at 120 (El País, 2025). Some may attribute this grim statistic to the harsh climate, geographical isolation, and limited daylight hours, but is the explanation really that simple? Inuit legends tell of elders who, feeling like a burden, would throw themselves off cliffs to spare their communities. While these are just stories, the reality is far more complex. Greenland is not alone in this crisis: Indigenous suicide is a global issue, seen in other regions like Australia and New Zealand.

Some scholars argue that the root causes of this trend lie in the rapid modernization process, the erosion of Indigenous languages and traditions, and the forced displacement from ancestral villages. As sociologist Maliina Abelsen explains:

“When you’re torn away from your own language, your own culture, your own identity, you feel alienated from society and from yourself. And instead of taking that frustration externally and sparking a revolution, you turn it inward and blame yourself for not being good enough. If you strip someone of what they are made of and they lose their identity, what follows is alcohol, and abuse, and violence, and suicide.”

Imminent Research Report 2025

A journey through localization, technology, language, and research.

The ultimate resource for understanding AI's impact on human interaction. Written by a global community of multidisciplinary experts. Designed to help navigate the innovation leap driven by automatic, affordable, and reliable translation technology.

Secure your copy nowAgainst Cultural Oblivion

Amid Greenland’s vast ice-covered landscape, the island stands as a symbol of cultural resilience, with Kalaallisut—the Greenlandic language—at its heart. More than just a tool for communication, Kalaallisut is the foundation of identity and a reflection of the country’s determination to break free from colonial influences. As Greenland moves toward self-determination and independence from Denmark, the language is a powerful emblem of reclaiming both cultural heritage and political sovereignty.

While colonial powers sought to replace indigenous culture with Danish language and customs, the Greenlandic language held steady, offering a quiet but powerful connection to local traditions. By the 1970s, this quiet resilience sparked activism, as young Greenlanders protested an education system that forced them to learn in a foreign language. They argued that reclaiming their language was crucial to rediscovering their true identity. The moment of change came in 1979 with the Home Rule Act, followed by Self-Government in 2009, both pivotal moments that strengthened Greenland’s political control. Recognizing Greenlandic as the official language marked a break from its colonial past and became a key step toward true cultural and political independence.

Greenlandic, part of the Inuit language family, includes three dialects: Kalaallisut (Western Greenlandic), Tunumiit oraasiat (Eastern Greenlandic), and Inuktun (spoken in the north). Known for its polysynthetic nature, the language’s structure allows for deep meanings to be expressed through single words, mirroring the Inuit worldview where language and the environment are intrinsically linked. This unique complexity is not a barrier but rather a cultural treasure, enabling the language to evolve in response to modern-day needs.

“The word oqaaseq means ‘word’; in its plural form, oqaatsit, it means ‘language.’“

Far from being left behind, Kalaallisut is thriving, bolstered by forward-thinking language policies and technological innovation. Pioneering initiatives like the Qimawin morphological parser, developed by Henrik Aagesen in 2004, and projects by Oqaasileriffik (The Language Secretariat of Greenland), established in 1999, have provided concrete tools to digitize and strengthen Kalaallisut. These efforts have made the language accessible in the digital age, bridging tradition with innovation. They have not only facilitated the processing and accurate interpretation of Greenlandic texts but also demonstrated that an indigenous language can flourish amid advanced technologies. Adapting Greenlandic to new technologies is more than a practical endeavor; it’s a bold affirmation of existence. While many indigenous languages face extinction, Greenlandic continues to be spoken, written, and passed down through generations, representing one of the Arctic’s most successful stories of linguistic and cultural resilience.

The modernization of Kalaallisut is intertwined with a broader strategy of cultural decolonization. Central to this is the indigenization of education—a priority that emerged from the student protests of the 1970s—which seeks to dismantle the barriers erected by a system that long relegated the mother tongue to a secondary status. Despite being the nation’s sole official language, the school system still grapples with colonial legacies. Much of higher education is conducted in Danish, posing significant challenges for Greenlandic students who grow up speaking their native language but face academic hurdles due to the dominance of Danish in academia and governance. The high dropout rate—nearly half of students do not complete higher education—reflects this dissonance. To address the issue, the Greenlandic government is training more native Greenlandic teachers and developing instructional materials in Kalaallisut. This battle for education in the Greenlandic language is, in essence, a fight for the nation’s future. Without a school system that reflects local culture, political self-determination remains incomplete.Today, Kalaallisut is not just the official language of Greenland but a symbol of the nation’s determination to shape its own future. In a world where cultural diversity is under threat, the language stands as a testament to resilience and innovation. With nearly all native Greenlanders using and identifying with Kalaallisut, every word spoken in the language is a reaffirmation of the country’s commitment to preserving its unique cultural identity and national autonomy.

A Traditional Way of Life Amid Modern Challenges

Independence for Greenland is far more complex than simply asserting sovereignty. The island’s economy strikes a delicate balance between tradition and modernity, where deep-rooted indigenous customs intersect with the pressures of globalization. To survive, Greenland depends on approximately 3.5 billion Danish kroner in subsidies annually from Denmark, which cover more than 50% of the public budget and account for around 25% of the GDP (Modern Diplomacy, 2025). These funds are essential for maintaining infrastructure, quality healthcare, and education, thus ensuring a Scandinavian standard of living that the Greenlandic population is hesitant to relinquish. However, this reliance on subsidies also limits Greenland’s ability to create a truly independent and sustainable economic model.

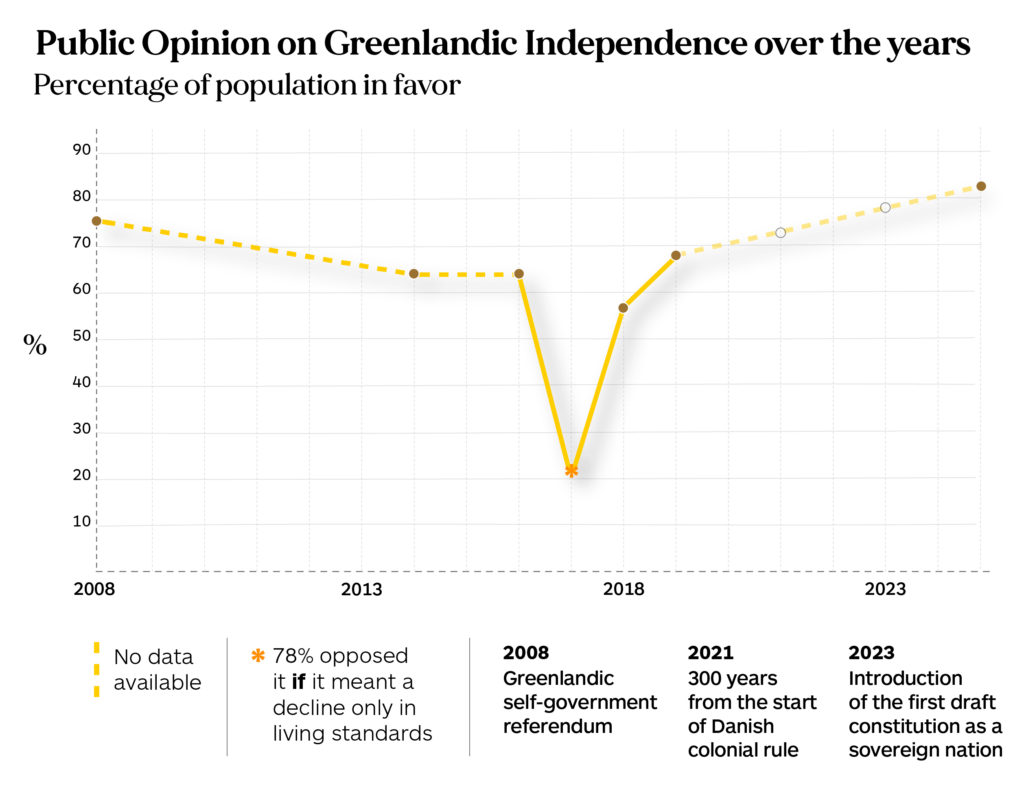

Source: Imminent

This reliance on Denmark’s support creates a double-edged sword. On one hand, the financial assistance and shared services—such as defense and infrastructure—provide stability and help maintain a decent standard of living. On the other hand, this dependence restricts Greenland’s ability to make autonomous decisions about its economic and political future. Studies (European Journal of Political Economy, 2022) and surveys conducted up to 2023 show that many Greenlanders are cautious about pursuing full independence, fearing that severing ties with Danish support could lead to a serious economic crisis. Greenland’s economic model is primarily built on two pillars: fishing, which makes up more than 90% of its exports (OEC, 2023), and a vast public sector that employs nearly 43% of Greenlanders (Statistics Greenland, 2024), further entrenching the island’s dependence on Denmark.

Fishing remains the driving force of Greenland’s economy. Here, maritime traditions and seafaring knowledge, passed down through generations, meet the demands of a modern economy that continues to struggle with structural fragility. Companies like Royal Greenland, leading in shrimp processing, have modernized the industry. However, this heavy reliance on a single sector exposes the island to global market fluctuations and environmental risks, including the overfishing of marine resources.

In tandem, the public sector not only serves as the primary employer but also acts as a social glue that binds a population dispersed across rugged terrain. With fewer than 100 miles of paved roads connecting its remote communities, transportation depends on ships, planes, and traditional methods like dog sleds and snowmobiles. This logistical challenge, combined with a shortage of skilled labor—exacerbated by emigration—maintains a high level of economic fragility.

In recent years, tourism has emerged as a glimmer of hope for diversification. From 2015 to 2019, visitor numbers grew by 20% annually, reaching 105,000 in 2019 (Tourism Statistics Report, 2019). However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the sector’s vulnerabilities, including its seasonality and a lack of infrastructure. These challenges, combined with a poorly diversified industrial base, render Greenland’s economic model fragile and form the core of arguments against full independence, which could be risky without significant economic stability.Despite these obstacles, Greenland holds vast untapped potential. Beyond its maritime wealth and Arctic traditions, the island is rich in opportunities for developing alternative economic sectors that could help it flourish. Sustainable tourism, agri-food products, and digital technologies present promising avenues for diversification. If these sectors are developed strategically, they could reduce Greenland’s dependence on external subsidies and pave the way for greater economic autonomy.