Global Perspectives

June 2025

What if I told you that the language you speak changes how you see the world?

In Peru, where dozens of languages intertwine, people don’t just mix cultures—they live with their contradictions. The Aymara people call this Ch’ixi (chee-khee): the art of holding opposites together without blending them into one. This idea challenges the common belief that cultures must “merge” to coexist. Instead, Ch’ixi shows us how Peru’s Indigenous, Spanish, and other linguistic traditions share space—clashing, adapting, and enriching each other, yet never fully dissolving.

Source: Translators Without Borders

The Andes and Quechua: Language of Circularity

A Worldview Based on Reciprocity

Today, more than ten million people speak Quechua, making it the most widely spoken pre-Columbian language in the Americas. Over the past fifty years, it has become an official language in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru—where it remains deeply rooted across twenty Andean regions (Planet Word Museum).

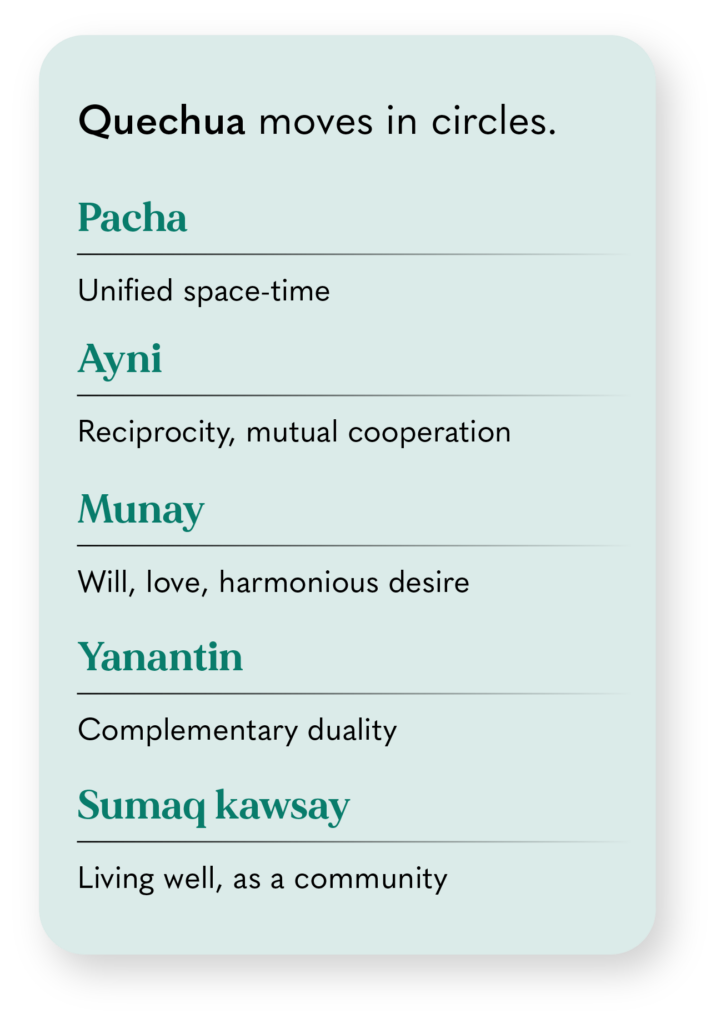

Selected words from the Quechua language that capture its essence (curated by Imminent)

Emerging from an Andean worldview where nature, spirit, and community are inseparable, Quechua holds a rich network of symbolic and spiritual meanings with no direct equivalent in Western languages. Nowhere is this connection more evident than in agricultural vocabulary. There are dozens of words for different varieties of tubers, potatoes, and sacred plants—many of which only grow in the highlands. The language therefore does more than classify; it preserves millennia of knowledge. These often untranslatable terms reflect a local ecological intelligence and a worldview grounded not in extraction, but in reciprocity and symbiosis with nature.

Likewise, Quechua also mirrors the reciprocity of a communal way of life. Words like ayni (reciprocity), mink’a (voluntary collective labor), or tinkuy (the harmonious meeting of distinct forces) are living principles still shaping daily life

Quechua’s Four Lives

Pre-Incan in origin and never silenced, it has withstood empires, colonization, and marginalization, becoming one of the world’s most enduring languages. Long before the arrival of the Spanish, this language was already the connective tissue of a vast civilization: the Tahuantinsuyo, or Inca Empire. Originally called Runasimi, or “the people’s language,” it gradually emerged as the empire’s lingua franca for two remarkably modern reasons.

First, it was the language of Qosqo (Cusco), the sacred and administrative center of imperial power. To speak it was to acknowledge the spiritual prestige and legitimacy of Inca rule.

The second reason lies in what modern linguists call a dialect continuum. Runasimi was – and still is – a container language: a network of interrelated dialects that remain mutually intelligible despite regional differences. Today, over 45 dialects are recognized, grouped into four major families (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) and spoken across the Northern, Central, and Southern Andes, with intelligibility rates between 70% and 90% (Library of Congress). Moreover, its agglutinative structure—where meanings are built by attaching multiple suffixes and prefixes—allowed it to absorb new concepts without losing coherence.

But this was only the first life of Quechua. Its second life began in 1560, with the publication of Gramática o arte de la lengua general de los indios de los reinos del Perú (“Grammar or Art of the General Language of the Indians of the Kingdoms of Peru”), authored by Dominican friar Domingo de Santo Tomás. It marked the first systematic effort to capture the complexity of Peru’s Indigenous languages in writing—not to preserve them, but to facilitate evangelization. Quechua, once oral and imperial, was transformed into a written colonial tool, codified through the structures of Latin.

This top-down codification marginalized many regional variants but gave Quechua a formal grammar that would help it survive centuries of suppression. Liturgical, legal, and bureaucratic texts kept the language alive in written form—allowing it to endure into its third life, following Peru’s independence in 1820.

In the newly formed republic, however, colonial hierarchies remained. In the name of national unity, Spanish was imposed as the language of education, governance, and social mobility. Quechua was excluded from institutions and relegated to rural life—dismissed as the speech of the “backward peasant.” It lost the religious prestige it once held and became a stigmatized vernacular.

Only in the second half of the 20th centuryQuechua began to reclaim public space. It reappeared in academic circles as a language essential to anthropology and ethnography. At the same time, it became a symbol of Indigenous identity and resistance across South America. These parallel movements culminated in a landmark moment in 1979, when Quechua was declared an official language of the Peruvian state.Still, formal recognition did not eliminate the underlying social inequalities. To this day, Quechua speakers continue to face discrimination in urban, educational, and administrative contexts. A 2018 report by Peru’s Ministry of Culture found that 59% of the population felt that Quechua peoples had experienced racial discrimination (El Peruano).

Back to the Roots

Despite such setbacks, the past few years have seen a slow but significant institutional shift. One striking example occurred in 2021, when the newly appointed Prime Minister of Peru delivered his inaugural speech entirely in Quechua. Moreover, intercultural protocols have been introduced in the healthcare sector. Public radio broadcasts in Quechua have increased. Parliamentary sessions now feature simultaneous translation. Plus, a nationwide literacy campaign has helped stabilize the number of active speakers. Today, over 500 rural schools provide bilingual education to more than 1.2 million children (AP News). These efforts may not heal centuries of exclusion, but they mark a turning point. Slowly, Quechua is shedding its label as a language of the past and becoming a voice for Peru’s intercultural future.

The new generation is leading the way into the Quechua language’s fourth—and so far, final—life. In a country increasingly flattened by the dominance of global languages like Spanish and English, this latest chapter marks a mythic return to the roots of imperial language—this time through digital realms.

Today, platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram have become virtual expressions of ayllu—communities of belonging—where thousands of young people share stories, music, and rituals with transnational audiences, including the Andean diaspora in the United States and Europe. These digital spaces have given rise to a powerful return to orality, where—as in ancient Runasimi—the message is shaped by context and performance.

In this fourth life, rap lyrics, Q-Pop, viral memes, and podcasts become modern-day megaphones of cultural resistance. Here, the rigid grammatical rules imposed from above are often abandoned. Instead, what emerges is a fluid and hybrid language, blending urban slang, tech neologisms, and ancient ritual phrases. It’s Quechua reborn—dynamic, playful, unapologetically evolving.This grassroots use of Quechua in digital media is more than just linguistic creativity—it’s a political act. Reclaiming the language from below means breaking free from colonial and republican frameworks and returning it to the people as a tool for self-representation.

Quechua doesn’t belong to the past. It moves in circles, still speaking to eternity.

Peru

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Discover it here!The Amazon and Its 40+ Tongues: Languages of Hidden Networks

Endangered Diversities

Looking down from the foothills of the Andes, a vast sea of green unfolds: the Peruvian Amazon —living system where language, ecology, and memory breathe together. Globally, the Amazon basin spans eight South American countries, hosts 10% of the world’s species (WWF), and shelters over 2.2 million Indigenous people, representing 410 ethnic groups, of which 80 live in voluntary isolation (World Bank).

Covering 60% of Peru’s territory but inhabited by less than 5% of its population (Wikipedia), the Amazon is home to immense biodiversity and cultural wealth: while they make up a small portion of the national population, they speak nearly half of Peru’s living languages—48 of 106.

These are not simply means of communication, but living systems shaped by ecology, ritual, and time reflecting a deep knowledge of the forest and its life. The Asháninka language, for instance, contains 47 terms for cassava; the Aguaruna track five winds based on their agricultural effect; the Shipibo-Konibo blend myth and zoology to name animals not just as fauna, but as spiritual actors. These vocabularies have evolved not despite isolation, but because of it—embedded in environmental stewardship, cyclical cosmologies, and sustainable land management.

Selected words from the Quechua language that capture its essence (curated by Imminent)

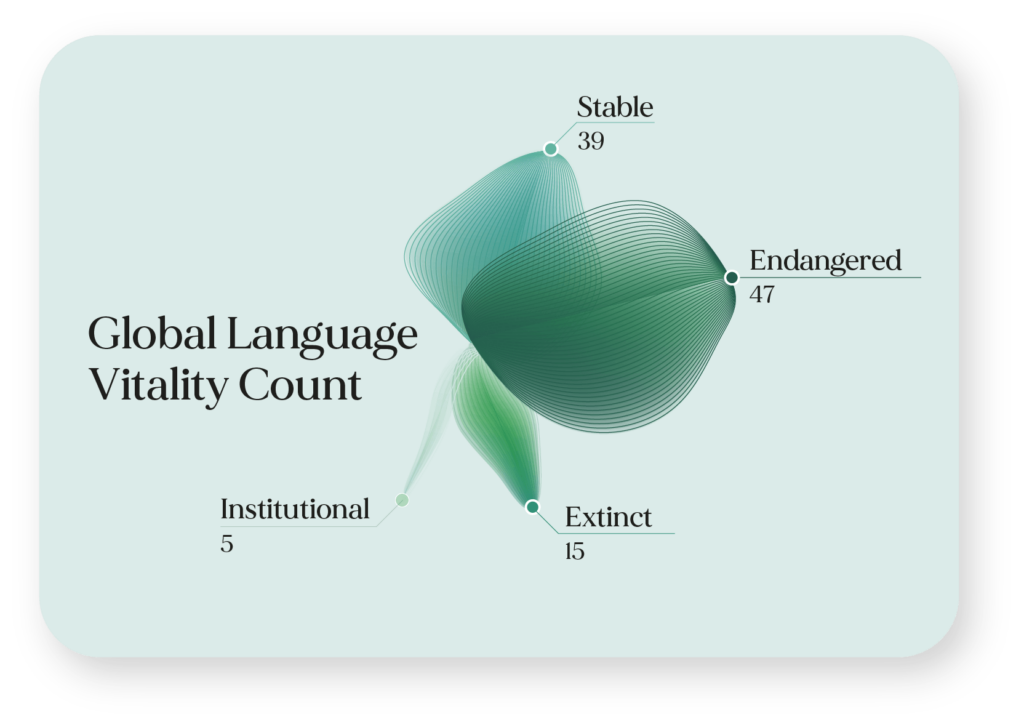

And yet, the rainforest’s invisibility in national consciousness mirrors the precariousness of its tongues. Despite their constitutional recognition, not one of the Amazonian languages holds co-official status in Peru. Most Indigenous children in the Amazon do not receive education in their mother tongue, and the majority of these languages rely on oral transmission—making them acutely vulnerable to migration, institutional neglect, and ecological collapse. UNESCO estimates that one indigenous language disappears every two weeks, and the Amazon languages reflect this reality: in Peru, 21 are critically endangered and 15 have already disappeared (UNESCO).

Their loss is not symbolic—it is systemic. Taushiro, an isolate once spoken in a now 98% deforested oil concession zone, survives in the memory of Amadeo García, who since 2017 has become the last speaker of the language, still remembering 47 terms for resin but no one to speak about them with.

A Radical Strategy of Survival

With this loss comes a greater defiance: organic systems of coexistence and preservation disappear along with the extinction of languages. Indigenous communities now occupy 2.4 million square kilometers of the Amazon, and 80% of that land remains forested. In fact, recent studies published in Nature show that Indigenous territories have significantly lower deforestation rates, not despite, but because of deeply embedded linguistic knowledge. (Fund the Planet).

And yet, the spaces where this knowledge persists are shrinking into a geography of opacity—zones left unmapped, unprotected, and unrepresented. Official cartographies label their lands as “desolate,” allowing extractive industries to encroach under the radar of the law. In Madre de Dios, unregulated gold mining has poisoned sacred rivers with mercury (IUCN NL), while deforestation projections estimate a 10% loss of forest cover by 2030 (Global Forest Watch)—leading to the extinction of plant species, place names, specific knowledge, and with them, unique systems of untranslatable words.

Source: Ethnologue

Meanwhile, as dominant languages like Spanish and Quechua become institutional filters for citizenship, education, and access to rights, Amazonian tongues are relegated to the periphery—treated as dialects rather than systems of knowledge. The result is triple erasure: legal, ecological, and linguistic. The educational system treats these languages as transitional; government policy ignores their conservation value; and families, displaced or pressured to assimilate, begin to trade their linguistic identity for urban survival.

But Amazonian languages are ecological technologies, cognitive maps, and ethical tools. The contradiction is brutal: in the age of climate crisis, we are erasing the very systems that hold the keys to sustainable futures. Their disappearance is a political choice, and if we fail to defend these languages, we are not only losing stories—we are losing instructions for survival.

The City and Limeño Spanish: Language of Hybridization

Laboratories of Hybridity

Urban centers like Lima are not simply spaces of residence but laboratories of hybridity, where waves of migration, colonization, aspiration, and exclusion have turned language into a living archive of survival and reinvention. To walk Lima’s streets is to listen to a city speaking many origins at once—and never in their pure form.

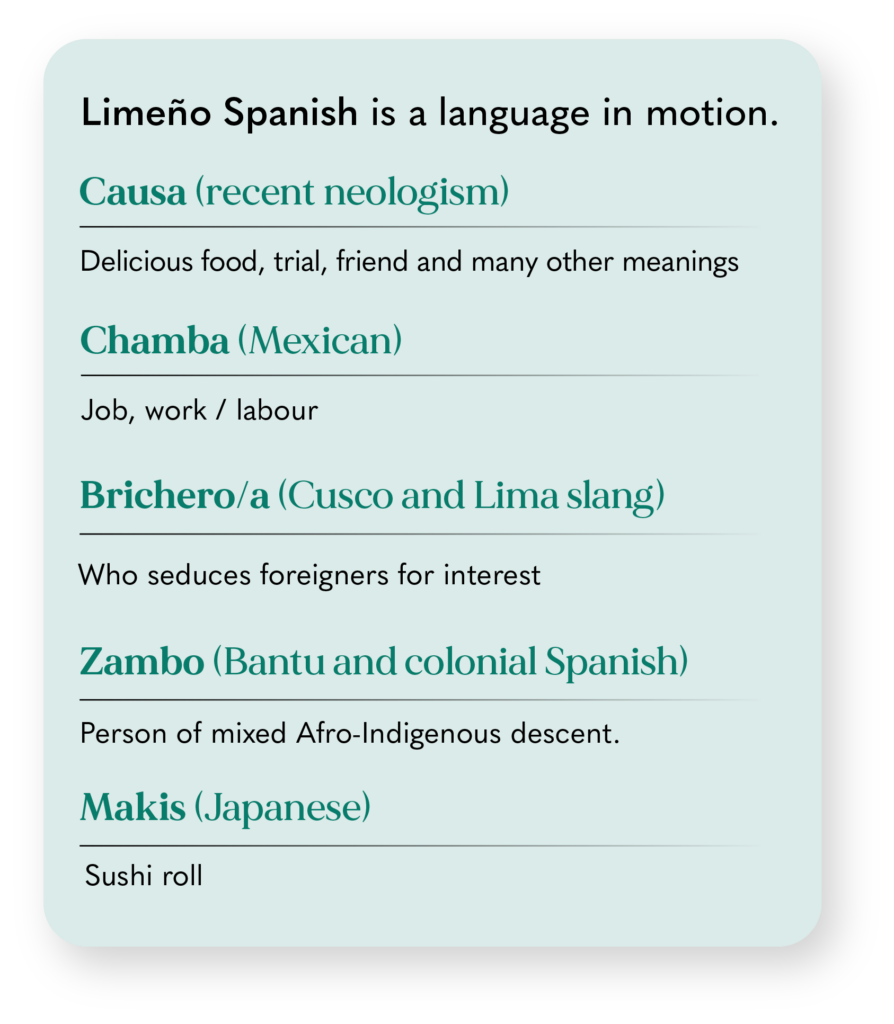

Selected words from the Quechua language that capture its essence (curated by Imminent)

The city’s linguistic chaos begins in conquest. Spanish, imposed in the 16th century as the imperial language, silenced dozens of Indigenous languages through laws, religion, and administration. For centuries, Spanish was not just a medium of power—it was power: the key to land titles, legal protection, and literacy. But the monolingual dream was always fragile. Peru’s cultural geography has never been that simple, and the 20th century tore open the illusion completely.

Between 1940 and 2025, Lima’s population exploded from 645,000 to over 11 million—an almost 17-fold increase (Macrotrends). This growth wasn’t organic—it was migratory. Driven by unequal land reform, poverty, the collapse of the agrarian economy, and later by civil conflict, millions of Indigenous and mestizo Peruvians from the highlands and Amazon migrated to coastal cities. Entire communities fled, often settling on Lima’s peripheries in self-built neighborhoods now known as the conos: Cono Norte, Cono Este, Cono Sur—sprawling urban belts that stretch around the city’s colonial core.

Mosaic of Identities

These conos—once dismissed as invasiones—are now home to millions. Over 60% of Lima’s population lives in these once-informal settlements, often with limited access to services (Goshen College). But they are not spaces of deprivation alone—they are spaces of negotiation, resistance, and invention. Here, the Andean migrants who arrived with Quechua, Aymara, and regional Spanish variants adapted their identities to urban life. Language mutated. Words like brichero (a young man who romantically targets tourists for upward mobility) or pitucada (behavior mimicking upper-class pretensions) emerged from a specifically urban experience.

In this linguistic evolution, Lima’s Spanish is no longer colonial—it is mestizo in syntax, multilingual in undercurrent. And this story is not only Andean. Peru’s cities have long absorbed foreign diasporas, each leaving distinct marks on the linguistic landscape. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, around 100,000 Chinese workers—coolies—were brought to Peru as laborers (Oxford Research Encyclopedias), primarily in coastal plantations and railroads. Though Cantonese itself did not survive widely, the laborers’ culinary and cultural legacy reshaped Peruvian Spanish: chaufa (fried rice), sillao (soy sauce), lonche (tea-time snack). Lima’s barrio chino (“Chinatown”) is now a culinary and commercial hub, where Mandarin resurfaces in signage, fusion cuisine, and generational identity.

On the other hand, the Japanese community, the second-largest in Latin America, began arriving in the 1890s, and by 2021, over 50,000 Peruvians identified as Nikkei (Japanese-Peruvian) (Research Gate). The Japanese influence in urban settings, however, is also less linguistic and more cultural. Recent years have added new voices to the mix. Since 2017, more than 1.5 million Venezuelans have entered Peru, escaping economic collapse and political repression: today, over 85% of Peru’s foreign-born population is Venezuelan (UNHCR). Their presence is reshaping Lima’s phonetics, with Caribbean rhythms, voceo, and typical Venezuelan expressions like chévere (awesome, cool) and burda (a lot, very) seeping into everyday urban Spanish, especially among young people.

The Social Engineering of Silence

Yet even as cities become more linguistically layered, language remains a gatekeeper. The prestige of ‘neutral’ Limeño Spanish—a slow, coastal, Hispanicized register—stands in contrast with the stigmatized serrano, veneco, and cholo accents. Linguistic discrimination, often invisible, functions as a soft architecture of exclusion: job opportunities, education, and even romantic desirability hinge on accent. In schools, children who speak Quechua at home are often mocked or punished, accelerating linguistic abandonment.

The city’s infrastructure mirrors this. Just as language stratifies access, Lima is physically divided. The infamous Muro de la Vergüenza—a six-kilometer concrete wall built to separate the affluent district of La Molina from the poorer neighborhoods of Villa María del Triunfo—embodies the social engineering of silence. On one side: gated communities, irrigated lawns, and private schools. On the other: water shortages, precarious housing, and overcrowded transit.

And yet, it is in these very margins that cultural innovation thrives: the conos are not passive recipients of culture but its most dynamic authors. As in many urban centers globally, neologisms emerging from Lima’s informal settlements—such as gilerazo (“overly flirtatious man”) or manazo (“blunder”)—show signs of widespread adoption among younger generations. These terms reflect not just playful creativity, but may also signal a shifting cultural center of gravity away from traditional elites.

What emerges is not purity, but synthesis. Peruvian cities, especially Lima, are spaces where the idea of a single identity collapses under the weight of accumulated crossings.

Research Report 2025 is rolling out!

A journey through localization, technology, language, and research.

The ultimate resource for understanding AI's impact on human interaction. Written by a global community of multidisciplinary experts. Designed to help navigate the innovation leap driven by automatic, affordable, and reliable translation technology.

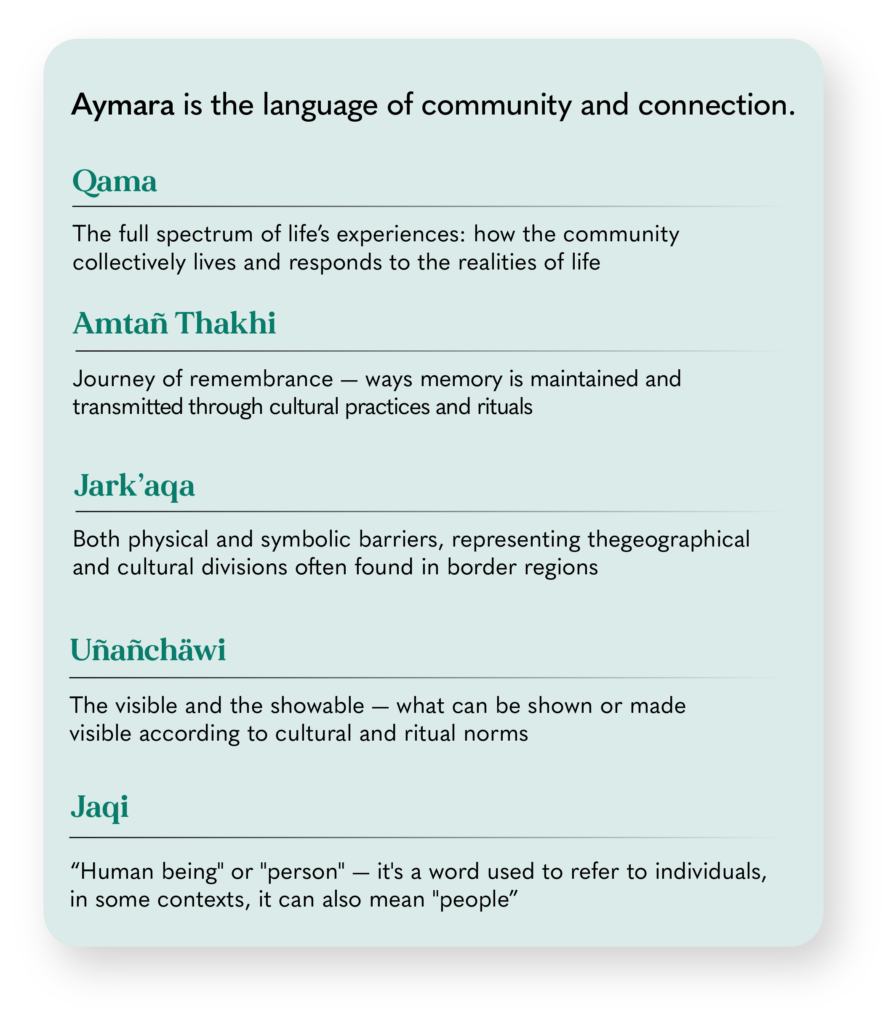

Secure your copy nowThe Southeast and Aymara: Language of Connection

Relational Intelligence

In the high-altitude borderlands where Peru fades into Bolivia and Chile, a language resists the silence imposed by centuries of erasure. Aymara, spoken today by over 2 million people—around 500,000 of whom in southern Peru—is not merely an Indigenous language but a living architecture of community and a grammar of belonging. Unlike Quechua’s broader territorial diffusion, Aymara spreads in depth across geopolitical frontiers, forming a tight-knit, rooted network of speakers whose identities transcend the nation-state.

Aymara’s grammar encodes a radically relational worldview. The first-person plural is dominant and reflects a communitarian cosmovision: Aymara distinguishes between “we-including-you” (jiwasa) and “we-excluding-you” (ñanaka), obliging the speaker to state, in every interaction, who belongs and who does not.

In this world, even nouns cannot exist alone: uma (“head”) must be possessed—uma-xa (“my head”), uma-ma (“your head”)—refusing the Western fiction of the self-contained individual. Identity in Aymara is always-with, never-alone.

Selected words from the Quechua language that capture its essence (curated by Imminent)

Similarly, verbs are obligatorily marked with evidential suffixes—-wa for direct experience, -ti for hearsay, -ch for inference—embedding in speech a compulsory awareness of how knowledge is known. This grammatical demand fosters a culture in which truth is never abstract or detached, but always situated, always entangled with context and responsibility.

This relational intelligence also found its way into unexpected domains. In the 1980s, NASA researchers explored the agglutinative structure of Aymara as a basis for early models of linguistic processing in AI. Its symmetrical, stackable suffixes—designed to convey precision without ambiguity—offered a compelling model for organizing information and structuring logic. For a moment, a language spoken by alpaca herders on the Andean altiplano became part of machine learning architecture, quietly unsettling the boundary between ancestral knowledge and technological innovation.

Culture in Motion

Yet this deeply communal language remains structurally marginalized in Peru. Despite its constitutional recognition as the country’s third official language and UNESCO’s designating it as Intangible Cultural Heritage, Aymara speakers continue to face limited access to bilingual education, digital infrastructure, and visibility in public data. There are no disaggregated statistics on how many Aymara-speaking children receive consistent instruction in their mother tongue. Similarly, most official documents, job applications, and media outputs remain Spanish-only. In public perception, Peru’s linguistic landscape is often simplified into two categories: Spanish and “other Indigenous languages.” This binary view obscures the specific realities and status of Aymara, as well as that of other distinct Indigenous languages in the country.

The result is linguistic displacement: in border cities like Juliaca and Tacna, Aymara young people often code-switch or abandon the language entirely to navigate economic survival. And still, Aymara endures. Unlike languages bound to fixed geographies or monolingual paradigms, Aymara thrives in threshold spaces: markets, migrant neighborhoods, WhatsApp chats straddling the Peru–Bolivia–Chile divide. Its strength lies in its ability to function as a flexible system of cultural continuity in motion.This threshold logic—what Bolivian sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui names ch’ixi, the coexistence of elements without fusion—explains why Aymara speakers often operate as nations within three states. Their citizenship is not bureaucratic but lived: a relational identity carried across borders for trade, ritual, and kinship. In practice, Aymara communities routinely navigate the porous seams of the Andes, challenging the Westphalian nation-state with a pan-Andean fabric of mutual aid and memory.e with a pan-Andean fabric of mutual aid and memory.

To speak Aymara is to position oneself ethically in a shared world, not as an isolated voice, but as part of a constellation of memory, place, and community. In a world fractured by individualism and disinformation, Aymara offers a syntax of care, an epistemology of relation, and a politics of thresholds.