Language

Remembering the Origin

Classical Arabic (and today Modern Standard Arabic) retains absolute institutional authority in Saudi Arabia. It is the language of education, religion, government, and media. Alongside it, however, everyday life unfolds in spoken varieties that are rooted locally yet ideologically tied to the prestige of the sacred language. Despite their internal diversity, Saudi dialects are widely perceived as the closest living forms to Classical Arabic, a perception grounded as much in religion as in linguistics.

To understand Saudi Arabic, one must begin not with grammar, but with space. The Arabian Peninsula is not only the geographic cradle of Arabic; it is also its symbolic core. For centuries, life in this region was shaped by desert nomadism, tribal organization, and limited contact with the outside world. Here linguistic exchange occurred primarily within tribes, not across empires. This long-standing isolation explains why Saudi dialects have preserved phonetic and lexical features that disappeared elsewhere in the Arab world. Saudi Arabic does not merely descend from Classical Arabic—it actively remembers it.

History, Diversity, and the Emergence of a Common Voice

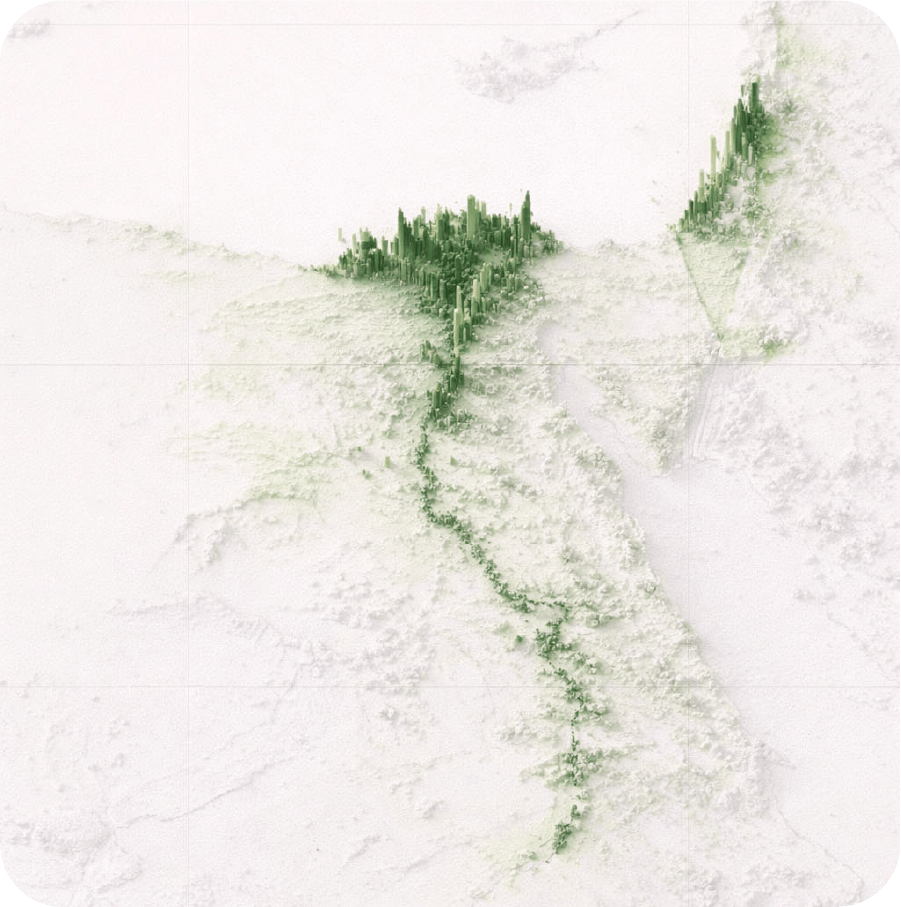

Arabic emerged in the Arabian Peninsula as early as the first millennium BCE and spread through trade and, later, Islamic expansion. As a Semitic language, it shares deep structural ties with Aramaic and Hebrew. Remarkably, this ancient linguistic landscape has not entirely vanished: minority communities in southern Saudi Arabia still speak languages such as Mehri and Khawlani, living traces of pre-Islamic Arabia.

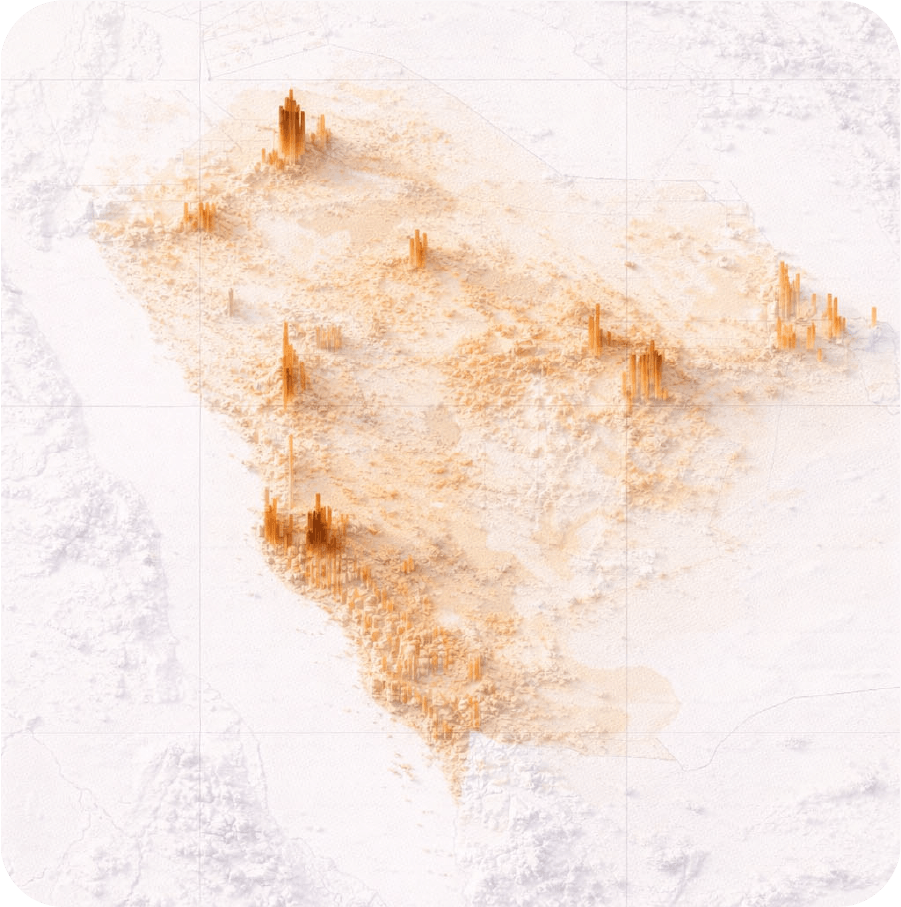

Today’s Saudi Arabia comprises thirteen administrative regions and a wide range of cultural and tribal histories. This diversity is mirrored linguistically. Each region developed its own dialect, shaped by settlement patterns, mobility, and contact—or lack thereof. Linguists estimate the existence of around sixty major local dialects, from which hundreds of micro-variants emerge. Some have faded over time, a natural process in all linguistic ecosystems.

At the same time, contemporary Saudi society has produced a unifying solution: a supra-regional colloquial variety often referred to as the “white language.” This flexible form blends elements of Classical Arabic with dominant urban dialects and allows mutual intelligibility across regions. Its spread reflects the growing influence of major cities such as Riyadh and Mecca, and marks a shift from strong local fragmentation toward a shared national linguistic space.

Geography as a Linguistic Framework

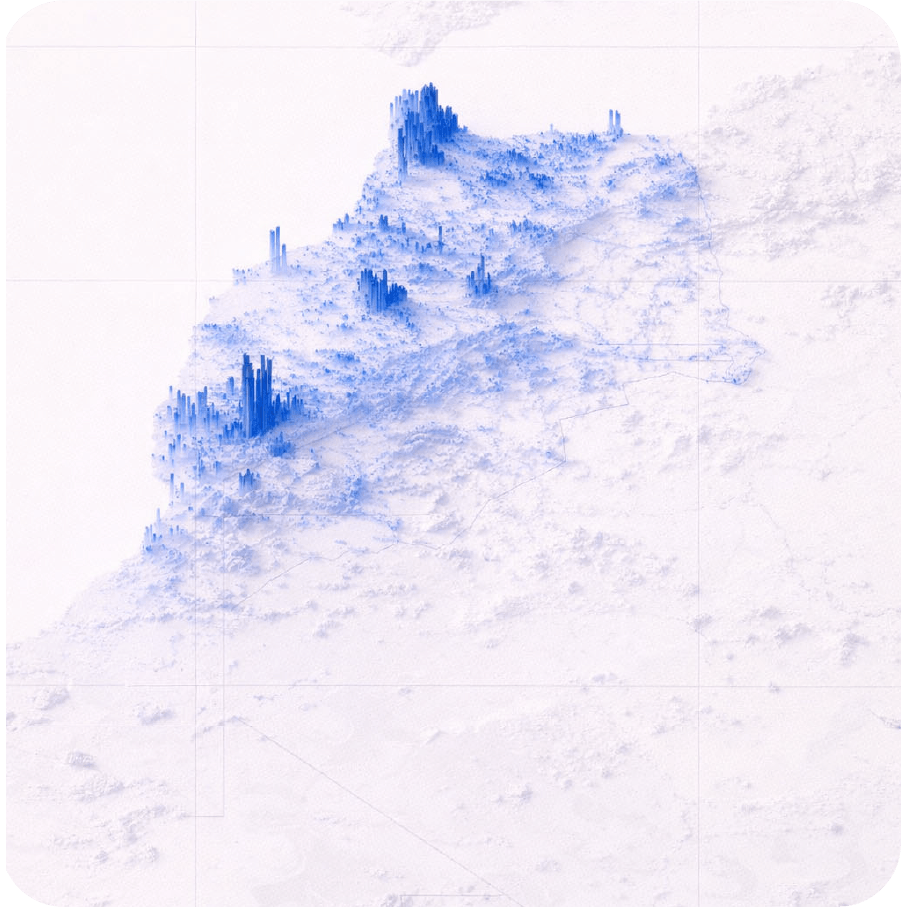

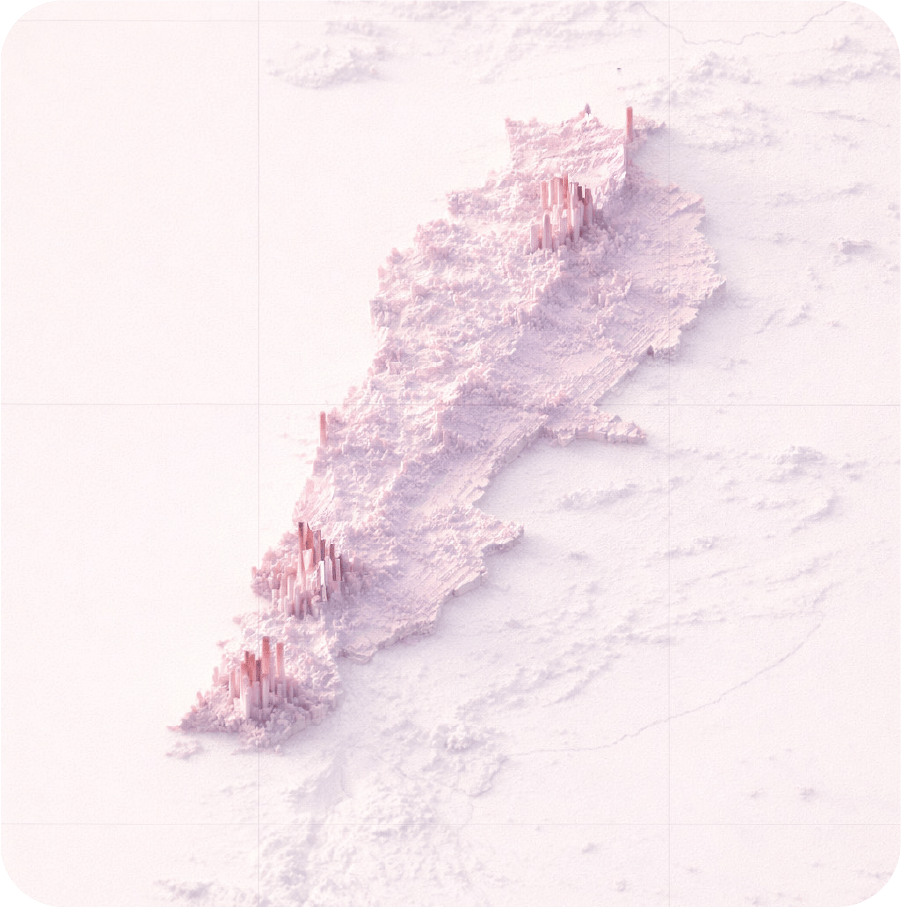

Saudi dialects are commonly grouped according to geography, although tribal affiliation, urban versus Bedouin heritage, and religious history also play important roles. Broadly speaking, there are four major dialect zones: Eastern, Western (Hijazi), Central (Najdi), and Southern. Within each zone, distinctions between urban and Bedouin speech remain significant, particularly in peripheral regions.

Eastern dialects, closely connected to the Gulf, are spoken in areas such as Al-Ahsa, Qatif, and Dammam. Western dialects belong to the Hijaz—Mecca, Medina, Jeddah—and reflect centuries of contact with pilgrims and traders. Central dialects, collectively known as Najdi, dominate the Najd Plateau and are spoken by millions, particularly in and around Riyadh. Southern dialects, found in Asir, Jizan, Najran, and the surrounding regions, are the most diverse and linguistically layered, sometimes blending Arabic with Himyaritic elements.

Saudi Arabic symbolizes origin, religious authority, and authenticity. Its sounds carry the weight of continuity.

Phonetic Memory and Tribal Speech

The most striking differences among Saudi dialects are phonetic. These are not random deviations, but survivals of ancient Arabic speech patterns described by early grammarians. Sound, in this context, becomes a marker of history and identity.

In the Hijaz, the phenomenon of taltala shifts the vowel of third-person singular verbs: “he knows” is pronounced [yeʿref] (يعرف) rather than [yaʿref], giving western speech a softer rhythm. In Al-Qassim, tadhajjuʾ slows articulation, reflecting Bedouin values of clarity and deliberation.

Southern dialects preserve kashkasha, where the feminine second-person ending becomes [ʃ]: [hala biʃ] (هلا بش) instead of [hala bik]. In Najd, a related feature called kaskasa replaces this with [s], producing [kef ales] (كيف ألس). Among older Najdi speakers, anʿana replaces the hamza with ʿayn, as in [aʃhad ʿnnak rasūl allāh], echoing early Arabic pronunciation. In Jizan, tamtamaniyya replaces the definite article al- with m-: [ṭibb mhawā] (طب مهوا) instead of ṭibb al-hawā.

Phonetic Variation in Saudi Arabic Dialects

| Phonetic | Lexique | |||

| [q] | [k] | [ʒ] | ||

| Eastern dialect | The consonant [q] is often pronounced [g]. E.g.:[iglet] = Come in! In the Al-Ahsa region, it is pronounced [ʒ]. E.g.:[feriʒ] = team | The consonant [k] changes to [tʃ]. E.g.:[tʃalb] = Dog | The consonant [ʒ] is often pronounced [j].E.g.:[wajah] instead of [waʒh] = Face | [zahba] = fast |

| Western dialect | The consonant [q] is often pronounced [g]. E.g.:[agis] = I believe | [k] E.g.:[balkan] = maybe | [dʒ] E.g.: [mkamedʒ] = rotten | [gwam] = fast |

| Central dialect | Stressed pronunciation of the consonant [g]E.g.: [glam] = Pencil | The consonant [k] changes to [ts]. E.g.:[tsalb] = Dog | The consonant [ʒ] is often pronounced [j] (especially in Riyadh). E.g.:[rajal] instead of [raʒʒal] = man | [igmez] = go fast |

| The Southern Region Dialect | The consonant [q] is often pronounced [ʒ]E.g.: [ʒafr] instead of [qafr] = An abandoned trace. | The [k] changes to [ʃ] at the end of the verb conjugated in the 2nd person feminine singular. E.g.: [kef hale ʃ] instead of [kef halek] = how are you? | The consonant [ʒ] is often pronounced [j] E.g.:[aljabl] instead of [alʒabal] = mountain | [ʃauer] = fast |

Sound as Regional Identity

Across the Kingdom, consonants act as audible markers of place. In the Eastern Province, [q] often becomes [g], as in [iglit] (“come in”), while in Al-Ahsa it may shift to [ʒ], as in [farīʒ] (“neighborhood”). The consonant [k] may become [tʃ] ([tʃalb], “dog”), and [ʒ] often softens to [j].

Central Najdi speech is marked by a strongly stressed [g], as in [glam] (“pencil”), and a shift of [k] to [ts]. Southern dialects once again stand apart, pronouncing [q] as [ʒ] ([ʒafr] instead of qafr) and preserving the feminine [ʃ] ending ([kef ḥāliʃ]).

Saudi Arabic in the Arab Dialect Continuum

When compared to other Arabic dialects, Saudi Arabic is consistently the most conservative. These patterns place Saudi Arabic closest to the Classical norm, followed by Levantine varieties. Egyptian and Moroccan dialects, shaped by stronger substrate influences and prolonged contact with non-Arabic languages, stand furthest away.

Lexical and Expressive Variation in Arabic Dialects

| Lexique-Expression | Classical Arabic | Saudi dialect | Levantine varieties | Egyptian dialect | Moroccan dialect |

| 1. “How are you?” | [kaifa halok] | [kif halak][ʃlonak] | [kifak][kif halak][ʃu akbarak] | [ɛzzajiak ][amel ɛ] | [kidajer][kif dajer] |

| Level of Similarity | Very | Very | None | None | |

| Nature of Difference | Phonetic | Phonetic + grammatical | Lexical | Lexical | |

| 2. “I’m fine” | [ana bikhɛr] | [bikhɛr][tajeb] | [mnih][mlih] | [kwajes] | [labas][bikhɛr] |

| Level of Similarity | Exact | Very | None | Synonymous | |

| Nature of Difference | – | Lexical | Lexical | Phonetic + lexical | |

| 3. “Now” | [al’ɑn] | [zalhin] | [halla’][hassa][halgɛt] | [dilwakt] | [daba] |

| Level of Similarity | Medium | None | Low | None | |

| Nature of Difference | Phonetic | Lexical | Synonymous | Lexical | |

| 4. “I want” | [uridu][abra] | [abi][abra] | [baddi] | [awɛz] | [brit] |

| Level of Similarity | Very | None | None | Very | |

| Nature of Difference | – | Lexical | Lexical | Phonetic | |

| 5. “What should I do?” | [maza ‘af’al] | [wɛʃ asaɥi] | [ʃu bamol][ʃu bsaɥi][ɛʃ asaɥi] | [amel ɛ] | [aʃ kadir] |

| Level of Similarity | None | Good | Good | None | |

| Nature of Difference | Lexical | Phonetic | Phonetic | Lexical | |

| 6. “Flip-flops” | [neal] | [neal] | [ʃehhat] | [ʃebʃeb] | [balra][babuʃ] |

| Level of Similarity | Exact | None | None | None | |

| Nature of Difference | – | Lexical | Lexical | Lexical |

Meaning Beyond Sound

This conservatism is not merely linguistic. In the Arab imagination, Saudi Arabic symbolizes origin, religious authority, and authenticity. Its sounds carry the weight of continuity. Yet this variety is not frozen in time. Urbanization, globalization, and youth culture increasingly introduce English loanwords and code-switching.

Saudi Arabic therefore occupies a unique position: It is both a living memory of Arabic’s beginnings and a dynamic system negotiating its future in a globalized world.

Samo Salim Saleh

Translator and Linguistics Researcher

She is a translator and linguistics researcher with extensive expertise in translation and Arabization. She earned her Master’s degree in Linguistics from the University of Caen-Bas-Normandy, France, in 2007. Over the years, she has published dozens of research papers in academic journals, covering topics in translation studies, Arabization, and language pedagogy. In addition to her research, she has taught foreign languages to non-specialists, combining academic insight with practical language instruction to support learners across diverse contexts.