Language

The Voice of the Arab World

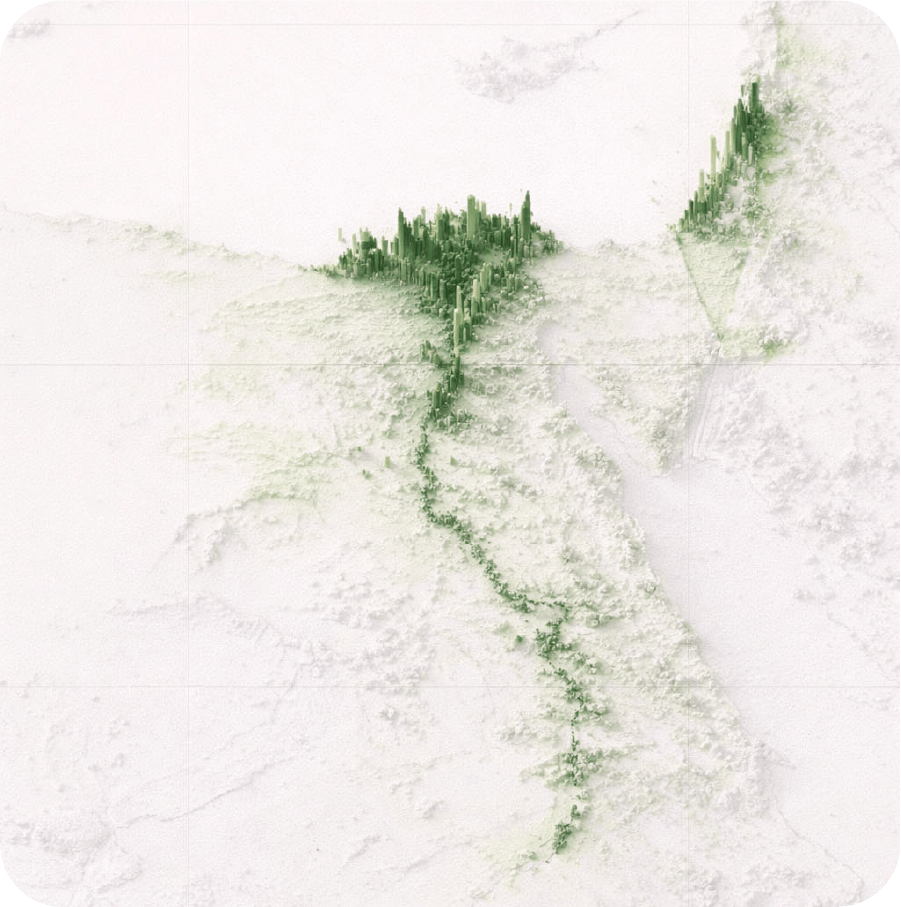

Egypt is not the geographic cradle of Arabic—that honor belongs to the Arabian Peninsula. It is not home to Islam’s holiest sites. Yet for nearly a century, Egyptian Arabic has been the Arab world’s most recognizable voice. This is the language of cinema, of songs that echoed across generations, of television series that captivated millions from Casablanca to Damascus.

Egyptian Arabic carries an unusual privilege: It is both deeply local and broadly accessible. It belongs entirely to Egypt, rooted in the rhythms of the Nile Valley and the memory of civilizations that predate Islam by millennia. Yet it speaks to the entire Arab world in ways no other colloquial dialect can match. This dual identity—profoundly Egyptian and simultaneously pan-Arab—makes it unique among Arabic varieties.

The Memory of Coptic

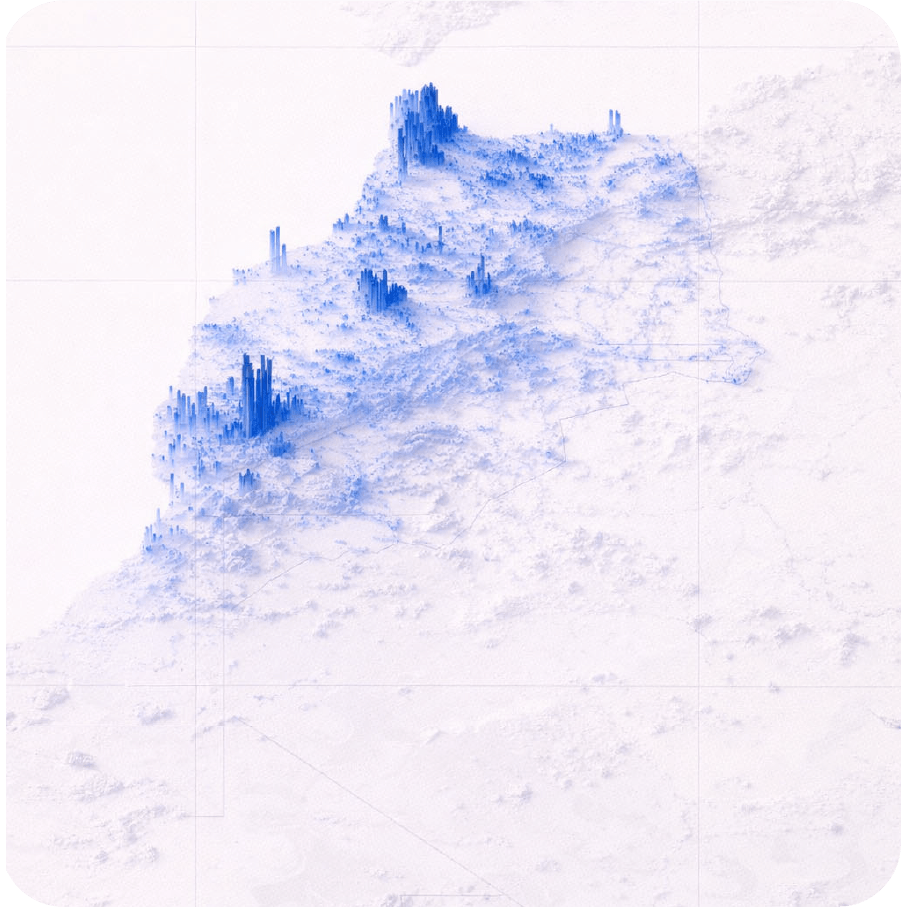

Egypt’s linguistic history did not begin with Arabic. For three millennia, the language of the pharaohs evolved through stages—Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, Demotic—until it arrived at Coptic, the final form of Ancient Egyptian. The transition to Arabic was neither swift nor complete. Coptic persisted for centuries after the conquest, particularly in Upper Egypt, where rural communities maintained it as their primary language well into the medieval period.

This long coexistence left marks. Coptic influenced how Egyptians would eventually speak Arabic—softening certain consonants, shaping pronunciation patterns, contributing words that had no Arabic equivalents. Even today, when Coptic exists only as a liturgical language preserved by priests of the Coptic Orthodox Church, its ghost whispers in Egyptian Arabic phonetics.

A Colloquial Lingua Franca

Egyptian Arabic emerged from this complex linguistic inheritance. As Arabic gradually displaced Coptic over centuries, it absorbed influences, adapted to local patterns, and developed features that would distinguish it from both its Arabian origins and neighboring dialects. By the twentieth century, Egyptian Arabic had crystallized into a recognizable variety with its own phonetic signature, grammatical innovations, and vocabulary.

What transformed Egyptian Arabic from a regional dialect into the Arab world’s most recognized voice was not linguistic evolution but cultural dominance. Egypt’s film industry, which began in the 1920s and reached its golden age in the 1950s through 1980s, broadcast Cairo’s dialect across the Arab world. Egyptian actors became household names. Their voices—warm, accessible, and unmistakably Egyptian—filled cinemas and later television screens from Casablanca to Damascus. Egyptian singers like Umm Kulthum and Abdel Halim Hafez sang in Egyptian Arabic, and their songs became the soundtrack of Arab life.

This cultural hegemony meant that even Arabs who never visited Egypt grew up hearing Egyptian Arabic. The result is a unique linguistic phenomenon: a colloquial dialect that functions across national boundaries. This cultural saturation had linguistic consequences. Egyptian Arabic became, in effect, the Arab world’s colloquial lingua franca—not replacing local dialects but existing alongside them as a shared reference point.

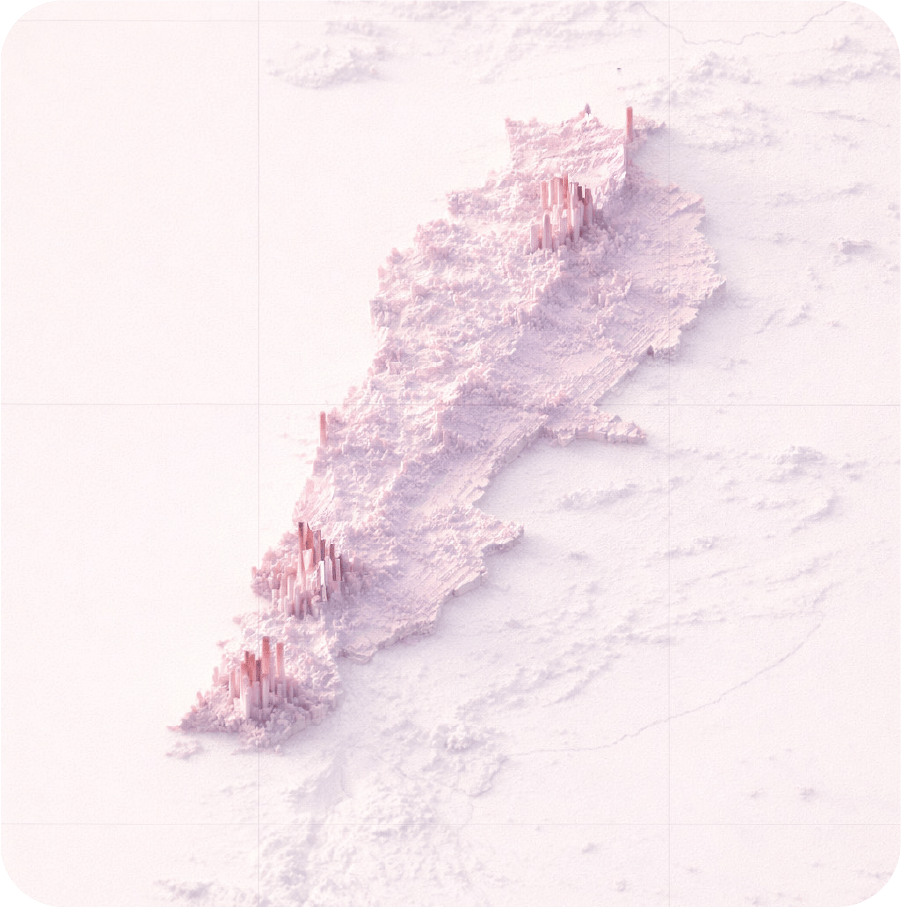

How Egyptian Arabic Sounds

The most immediate marker of Egyptian Arabic is what happens to the letter jīm (ج). Where Classical Arabic and most other dialects pronounce it as a soft “j,” Egyptians turn it hard: jamīl (beautiful) becomes gamīl, and jāmiʿa (university) becomes gamʿa. This single phonetic shift acts as an instant identifier.

The Classical Arabic qāf (ق) undergoes an even more dramatic transformation. In many Egyptian words, it softens to a glottal stop or disappears entirely. The word qalb (heart) becomes alb. The verb qāla (he said) becomes āl. Linguists debate whether this reflects Coptic substrate influence or internal Arabic development, but the result is distinctive: Egyptian Arabic sounds softer, more flowing than its Gulf or Levantine counterparts.

Yet Egyptian Arabic maintains clarity. Unlike Moroccan dialects, which compress syllables until comprehension becomes challenging for other Arabs, Egyptian preserves an accessible phonetic profile. This clarity, combined with media saturation, explains why Egyptian Arabic remains widely intelligible even to speakers who cannot produce it themselves.

This cultural saturation had linguistic consequences. Egyptian Arabic became, in effect, the Arab world’s colloquial lingua franca.

The Grammar of the Streets

Egyptian Arabic’s grammatical innovations reveal how spoken language evolves away from classical norms. The most distinctive feature is the bi- prefix, which marks present tense verbs for ongoing or habitual action. It distinguishes between ongoing actions and general truths more precisely than Classical Arabic typically does.

The bi- prefix (borrowed from Coptic’s aspectual system) creates temporal precision absent in Classical Arabic.

Present Tense: Classical and Egyptian Arabic

| Function | Classical Arabic | Egyptian Arabic | Usage |

| Simple present | yaktub يكتب | yiktib يكتب | Ability or general truth |

| Present continuous | yaktub يكتب | biyiktib بيكتب | Ongoing action right now |

| First person | aktubu أكتب | bakrah بكره | The prefix becomes ba- |

Huwwa biyiktib means “he’s writing right now,” while huwwa yiktib means “he writes”, referring to an ability or habit. This distinction, commonplace in English, found natural expression in Egyptian Arabic through grammatical innovation.

For future time, Egyptian uses the particle ḥa- before any verb: ḥasāfir bukra (I’m going to travel tomorrow), ḥaniftaḥ maḥall gidīd (we’re going to open a new shop). This replaces Classical Arabic’s more complex constructions, making future intention immediate and concrete.

Tense Forms: Classical vs. Egyptian Arabic

| Tense | Classical Arabic | Egyptian Arabic | Translation |

| Present | adrusu أدرس | badrus بدرس | I study / I am studying |

| Future | sa-adrusu سأدرس | ḥadrus حدرس | I will study |

| Past | qaraʾtu قرأت | arayt قريت | I read |

These grammatical innovations completely change some colloquial expressions. Consider how a simple question transforms between Classical and Egyptian Arabic:

Classical Arabic: Ayna tadhhabu? (Where are you going?)

Egyptian Arabic: Rāyiḥ fēn? (Going where?)

The Egyptian version is shorter, more direct, built from pieces that feel more like natural speech than grammatical construction. This pattern—using participles instead of conjugated verbs, colloquial question words instead of classical ones—is repeated throughout Egyptian Arabic.

Words That Changed

Lexical divergence runs deep. Egyptian Arabic developed its own lexicon, sometimes preserving Classical roots, sometimes innovating entirely. The word for “now” illustrates this: Classical Arabic uses al-ān, but Egyptian says dilwaʾti—literally “this time.” The word for “what” becomes ēh instead of mādhā. “How” becomes izzay instead of kayfa.

Furthermore, common Egyptian expressions emerged that have no Classical equivalent. Maʿlēsh (never mind, it’s okay) carries resignation, forgiveness, and pragmatism in a single word. Mafīš muškilah (no problem) and ṭayyib (okay, alright) pepper everyday conversation. These words, forged in streets and homes, carry emotional registers that formal Arabic cannot quite capture.

Meanwhile, foreign influence appears but remains superficial. Modern loanwords from English—mōbāyl (mobile phone), tilivizyōn (television)—or French—asansēr (elevator)—serve practical needs when Arabic equivalents feel cumbersome. Yet compared to Morocco, where French permeates everyday speech, or Gulf dialects increasingly saturated with English, Egyptian Arabic absorbs foreign terms pragmatically while keeping its core vocabulary Arabic.

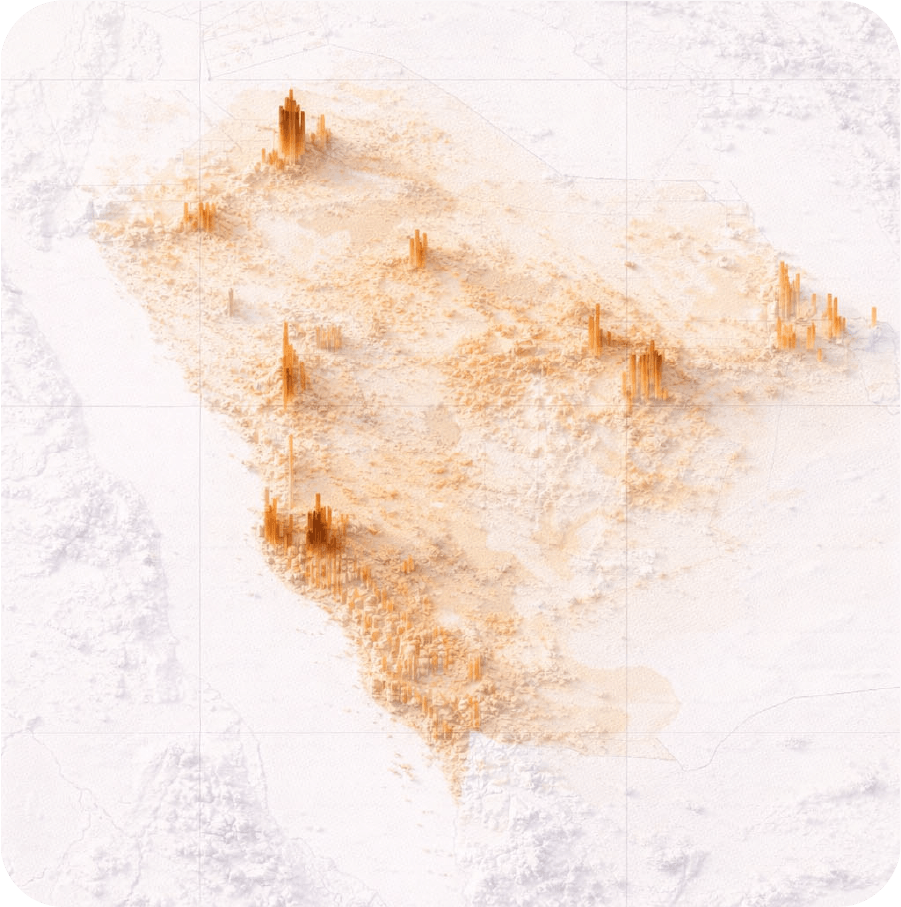

Egyptian Arabic in the Dialect Continuum

Place Egyptian Arabic on a spectrum from Classical Arabic to Moroccan Darija, and it occupies middle ground—distinctly colloquial yet broadly accessible. Consider how a simple greeting transforms across the Arab world:

Arabic Greetings: Dialect Comparison

| Dialect | “How are you?” | “I’m fine” | Similarity to Classical |

| Classical | kayfa ḥāluka? كيف حالك | ana bikhayr أنا بخير | __ |

| Saudi/Gulf | kayf ḥālak? كيف حالكšlōnak? شلونك | bikhayr بخير | Very similar |

| Egyptian | izzayyak? ازيكʿāmil ēh? عامل ايه | kwayyis كويس | Completely different |

| Levantine | kīfak? كيفكšū aḫbārak? شو اخبارك | mniḥ منيح | Moderately different |

| Moroccan | kīdāyir? كيدايرlabās? لاباس | labās لاباس | Very different |

Egyptian falls roughly in the middle—more divergent than Gulf dialects, more accessible than Moroccan. This positioning helps explain its widespread intelligibility. It innovates without becoming opaque.

The same pattern appears in everyday vocabulary. Where Classical Arabic says al-ān (now), Saudi uses ḥalḥīn, Levantine hallaʾ, Egyptian dilwaʾti, and Moroccan daba. For “I want,” Classical has urīdu, Saudi abī, Levantine baddī, Egyptian ʿāwiz, Moroccan bḡīt. Egyptian consistently maintains its own forms while remaining within bounds of pan-Arab comprehension.

The Living Language

Egyptian Arabic today exists in dynamic tension between tradition and transformation. It preserves Coptic influences in its phonetics, remembers Classical Arabic in much of its vocabulary, yet constantly adapts to contemporary needs. Young Egyptians mix Arabic with English in patterns that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. Social media has created new registers and abbreviations; technology introduces vocabulary that must be negotiated.

Yet the core remains recognizably Egyptian. The bi- prefix still marks the present tense. The ḥa- particle still indicates the future. The hard “g” still replaces a soft “j.” These features, developed over centuries of Egyptian life, persist even as the language continues to evolve.

Egyptian Arabic is neither the most conservative dialect—that honor belongs to varieties spoken in the Arabian Peninsula—nor the most innovative. It is, however, the most visible, the most widely heard, the most familiar to Arabs who do not speak it natively. Through cinema, music, and television, it became the Arab world’s shared colloquial reference point, a dialect that belongs to Egypt yet speaks to everyone.