Language

The Westernmost Edge

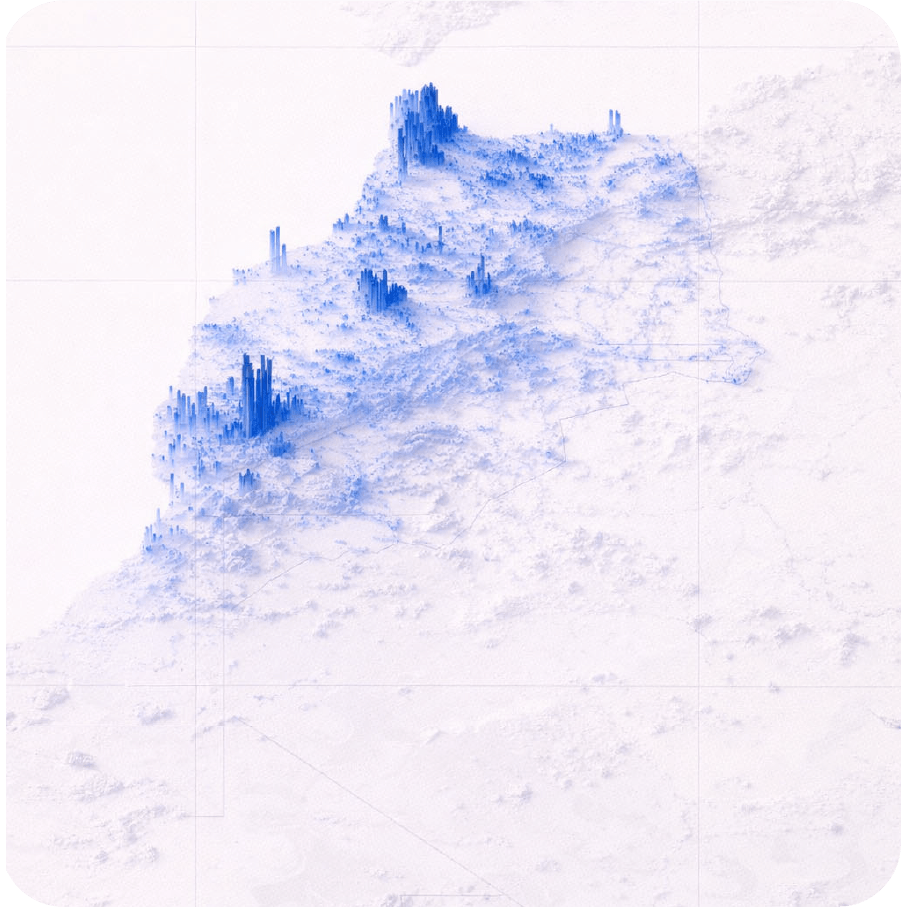

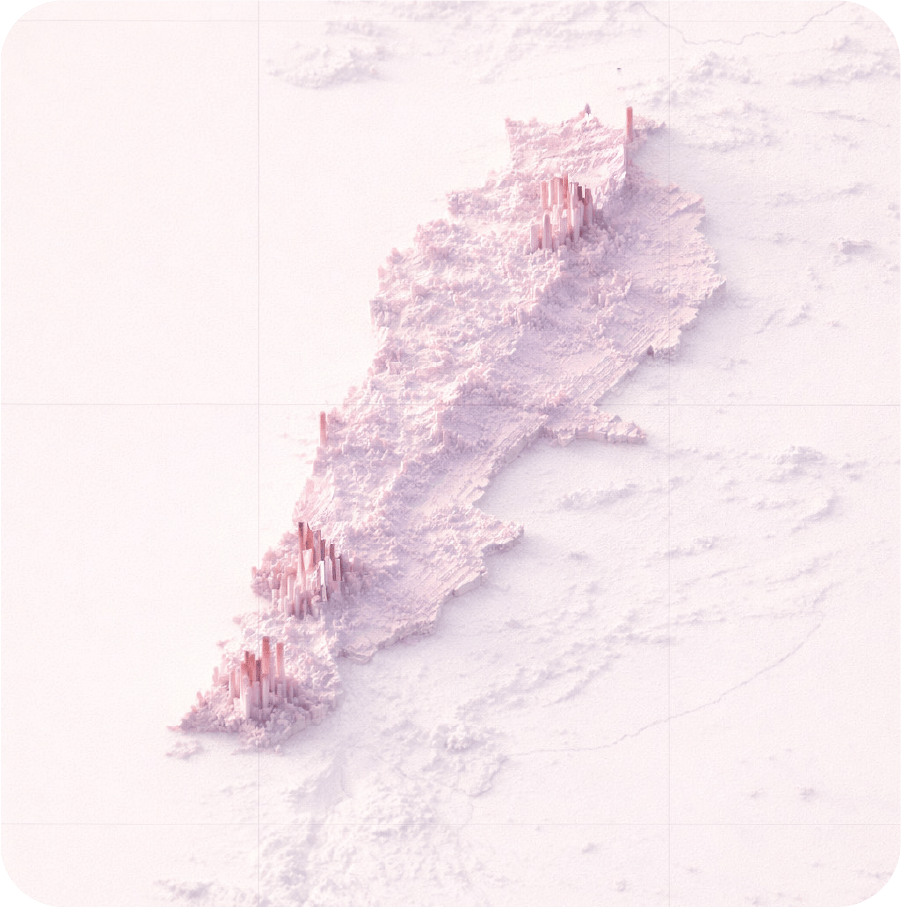

If Egyptian Arabic is the Arab world’s most recognized voice, Moroccan Arabic, also known as Darija, is its most mysterious. The linguistic distance between Cairo and Casablanca is not merely geographic but fundamental. Moroccan Arabic stands at the westernmost edge of the Arabic dialect continuum, and from that position, it has evolved into something that challenges the very concept of mutual intelligibility within the Arab world.

This divergence is not accidental. Morocco sits at the terminus of Arabic’s expansion, thousands of kilometers from the Arabian Peninsula, separated from the eastern Arab world by the entire breadth of North Africa. More significantly, it sits on land that was Berber for millennia before Arab armies arrived. The collision between Arabic and Berber, later enriched by Romance languages during colonial occupation, produced something unique: a vernacular so transformed from Classical Arabic that many Arabs hearing it for the first time wonder if it is Arabic at all.

Yet Moroccans call it əl3ərbiyya—Arabic—or more commonly əddariža (Darija), meaning “the common language,” the everyday tongue of the Kingdom’s population. According to the 2024 census, 91.9% of Moroccans speak Darija. It is the language of streets and homes, of markets and cafes, of Moroccan life in all its dimensions.

Two Waves, Two Arabics

Arabic did not come to Morocco in a single wave but in two distinct migrations that left separate linguistic imprints. The first wave followed the Islamic conquests of the eighth century. These early Arab settlers established communities in northern cities—Fes, Tangier, Tetouan, Rabat—and their Arabic, called “pre-Hilalian,” was more conservative, closer to Classical forms. It survives today in the prestigious urban dialects of Morocco’s old imperial cities.

The second wave came centuries later and changed everything. Between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, massive Bedouin tribes swept across northern Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic. This “Hilalian invasion” gave Arabic its definitive foothold in northwestern Africa. The Bedouin brought their own Arabic, phonetically and lexically distinct from what the early settlers had introduced, and it established itself primarily on Morocco’s Atlantic plains.

When France made Rabat the capital in 1912 and developed Casablanca as Morocco’s economic center, massive migration from the Arabic-speaking Atlantic plains to these new power centers established Hilalian Arabic as the national standard. The countrymen’s dialect became the city’s dialect, and from there, the nation’s.

The collision between Arabic and Berber, later enriched by Romance languages during colonial occupation, produced something unique: a vernacular so transformed from Classical Arabic that many Arabs hearing it for the first time wonder if it is Arabic at all.

The Sound of Rupture

The first thing that strikes anyone familiar with other Arabic dialects when encountering Moroccan Arabic is how different it sounds. This is not merely accent but fundamental phonological transformation.

The Bedouin and Berber Mark

Classical Arabic distinguishes several interdental consonants—sounds formed by placing the tongue between the teeth. Moroccan Arabic drops them entirely. The word daǧāǧ (chicken) in Standard Arabic becomes džaž in Moroccan. This is clearly Berber influence—Berber languages ignore interdentals entirely, and Moroccan Arabic is the North African variety most averse to interdentals.

Furthermore, where Standard Arabic says qāla (he said), Moroccan says gal. This shift of /q/ to /g/ in verbs marks clear Bedouin influence from the Hilalian migrations. The preservation of /q/ betrays pre-Hilalian northern origins.

Fassi Arabic, the prestigious dialect of Fes, presents a notable exception. There, /q/ becomes a glottal stop in all contexts, much like Egyptian Arabic. Fassi speakers also transform the Arabic /r/ into something resembling the American English “r”, a distinctive phonetic signature marking Fes’s linguistic prestige.

Vowels Compressed

Perhaps the most dramatic transformation occurs in Moroccan Arabic’s vowel system. Classical Arabic distinguishes three pairs of vowels: short and long /a/, /u/, and /i/. Moroccan Arabic reduces this to essentially four vowels, or five including the schwa, /ə/. The transformation follows a pattern: Classical Arabic’s long vowels remain, but short vowels compress toward a schwa sound. Standard Arabic madīna (city) becomes mədina in Moroccan.

Moroccan Arabic’s Vowel System

| Classical Arabic | Darija |

| /a/ | /ə/ (remains the same when in final position) |

| /ā/ | /a/ |

| /u/ | /ə/ (South); /ŭ/ (North) |

| /ū/ | /u/ |

| /i/ | /ə/ |

| /ī/ | /i/ |

This vowel reduction reflects Berber influence—Berber languages ignore vocalic length and typically have only three vowels. The result is that Moroccan Arabic compresses words into consonant clusters that challenge uninitiated ears. Where Egyptian Arabic maintains phonetic clarity, Moroccan elides syllables in ways that make it almost impenetrable to Eastern Arabic speakers.

Moroccan also suppresses diphthongs. Al-mawlid (the Prophet’s birth) becomes əlmuləd, and bayt (house) becomes bit. The preservation of diphthongs marks rural speech—where urban speakers say fink (where are you?), rural speakers maintain faynk, preserving a more conservative phonological trait.

How Moroccan Arabic Works

In general, Moroccan Arabic’s grammar reveals distinctive innovations. The most notable concerns second-person singular endings. Where Standard Arabic distinguishes ḏahabta (you went, masculine) from ḏahabti (you went, feminine), Moroccan simply says mšiti for both. Among Maghrebi dialects, only Moroccan does this—a gender-neutral construction that sets it apart even from its closest neighbors.

Moreover, the first-person singular imperfect takes the prefix n-, characteristic of all Maghrebi dialects from Libya to Mauritania: ka-ngləs (I am sitting), nšuf (I will see). This single marker instantly identifies North African Arabic to any listener.

For negation, Moroccan employs the circumfix ma-…-š(i), wrapping verbs in negation: mša (he went) becomes ma-mša-š(he didn’t go). This pattern, shared with Egyptian and other North African dialects, creates a rhythmic symmetry absent from other negation strategies.

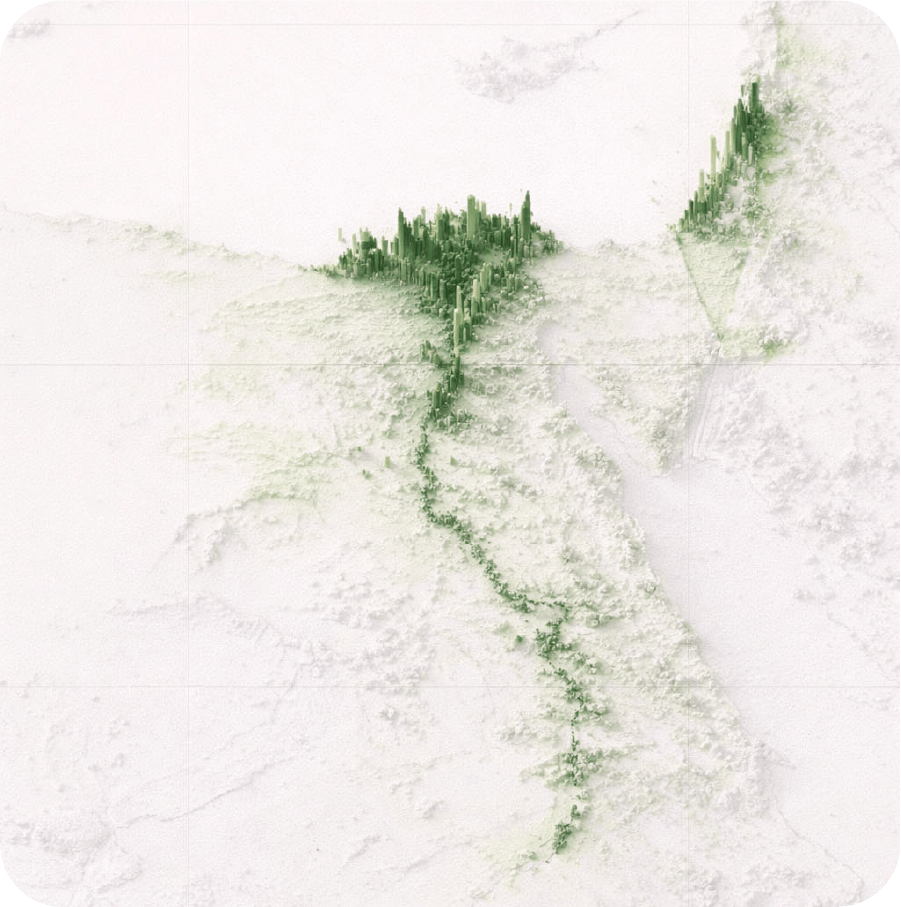

The Berber Foundation

No understanding of Moroccan Arabic is complete without reckoning with Berber influence. Berber is North Africa’s oldest attested language family, spoken for millennia before Arab armies arrived. For centuries, Arabic and Berber have coexisted, interpenetrated, influenced each other, and today, a significant minority still speaks Berber languages.

Berber words permeate Moroccan Arabic’s most basic vocabulary. This influence penetrated even Hassaniya Arabic—the conservative Bedouin dialect of Morocco’s Saharan provinces.

Moroccan Darija Lexicon with Berber Origins

| Category | Moroccan Darija | Berber Source | English |

| Nouns | əssarut السروت | tasarut | key |

| əlmšš المشش | amušš | cat | |

| walu والو | walu | nothing | |

| əlməzwar المزوار | amzwaru (first) | traditional administrative position | |

| Verbs | krəm كرم | krəm (to freeze) | to dry |

| kəmi كمي | kəmi | to smoke | |

| Adverbs | ġir غير | ġir | only, just |

| nišan نيشان | nišan | directly, exactly |

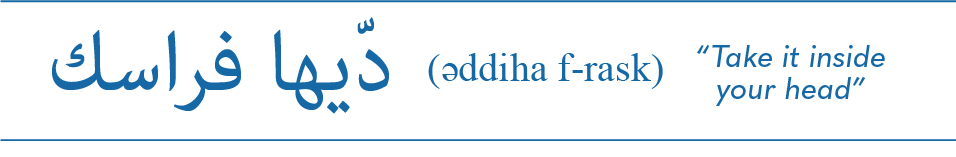

But Berber influence extends beyond vocabulary into the very structure of thought. The Moroccan Arabic expression for “mind your business” is əddiha f-rask—literally “take it inside your head.” This makes no more sense in Standard Arabic than in English, but it has an exact word-for-word equivalent in Berber: awi-tt ġ-ugayyu-nnək. This reveals a Berber semantic substratum—ways of thinking and expressing embedded in Moroccan Arabic.

Berber also affected grammar. The dual almost disappeared except for timespans: yumayn (two days), šəhrayn (two months). To express indefiniteness, Moroccan borrowed a Berber construction: adding wahəd (one) before the definite noun. Əl-bit (the house) becomes wahəd əl-bit (a house)—a pattern that feels natural to Moroccan speakers but strange to Eastern Arabs.

Colonial Layers

France’s protectorate from 1912 to 1956 left linguistic traces that persist to this day. French remains the primary medium of higher education and the working language in administration and private firms. French borrowings concentrate in technological fields, and many are so embedded that Moroccan Arabic’s grammatical rules apply to them.

French Loanwords in Moroccan Darija

| French | Moroccan Darija | Arabic Script | English | Integration |

| télévision | əttlfaza | التلفازة | television | Fully Arabized |

| automobile | əṭṭumubil | الطوموبيل | car | Fully Arabized |

| timbre | əttanbər | التنبر | stamp | Takes Arabic broken plural: tənabər |

| clé à molette | klamuniṭ | كلامونيط | wrench | Morphology adapted |

| valise | baliza | باليزة | suitcase | /v/ → /b/ adaptation |

However, Spain also controlled northern Morocco during the protectorate, and Spanish left its own lexical imprint on everyday vocabulary. Spanish influence is concentrated in northern dialects, but even there, French has supplanted Spanish as the prestige foreign language.

Spanish Loanwords in Moroccan Darija

| Spanish | Moroccan Darija | Arabic Script | English |

| semana | əssimana | السيمانة | week |

| zapato | əssəbbat | السباط | shoe |

| rueda | ərrwida | الرويضة | wheel |

| manta | manta | مانطة | blanket |

Over the last two decades, however, English has gained enormous traction among Morocco’s youth under the influence of American pop culture. Urban young people do with English what their parents’ generation did with French—code-switching as identity marker, loanwords penetrating everyday speech. The full scope awaits assessment, but the trend is unmistakable: English is becoming Morocco’s newest linguistic layer.

The Intelligibility Problem

Thanks to Egyptian and Levantine media dominance from the 1950s through 1990s, many Moroccans developed at least a passive comprehension of Eastern dialects. They watched Egyptian films, listened to Levantine music, and absorbed Eastern Arabic through cultural consumption. But Morocco produced no comparable media soft power, so Eastern Arabs never developed familiarity with Moroccan speech.

The result: intelligibility flows one way, from East to West. This linguistic isolation reinforces Morocco’s position at the western periphery of the Arab world—geographically distant, linguistically divergent, culturally distinct. Moroccan Arabic is therefore unquestionably Arabic—yet it has diverged so dramatically that it challenges the concept of Arabic as a unified linguistic community.

Badre Ghiyati

Professional librarian, Translator, and content Writer

Badre Ghiyati is a professional Librarian/Documentalist, Translator, and Content Writer specializing in Arabic, French, and English. With over 11 years of experience, he has collaborated with both national and international translation platforms, including Translated, delivering high-quality linguistic services that ensure a precise and nuanced understanding of documents.Alongside translation work, Badre Ghiyati has worked within academic institutions, universities, governmental libraries, with core responsibilities including managing cataloging, classification, assisting patrons, research documentation, and managing resources (print and digital).