Language

A Mosaic in Sound

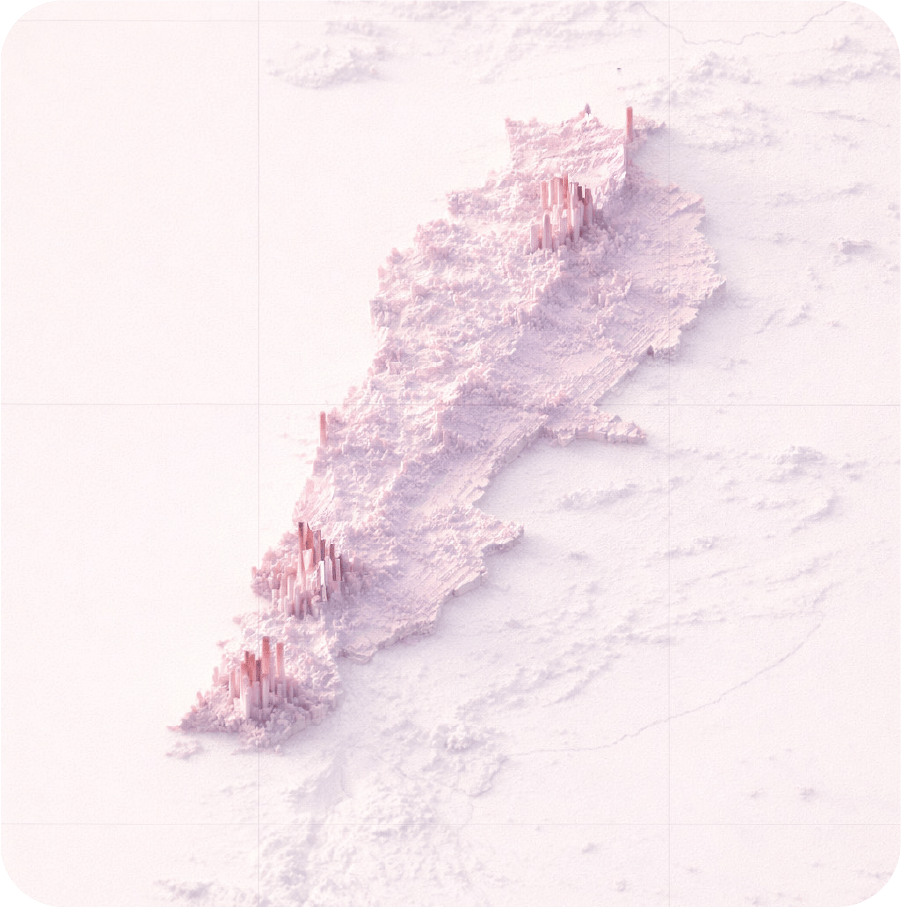

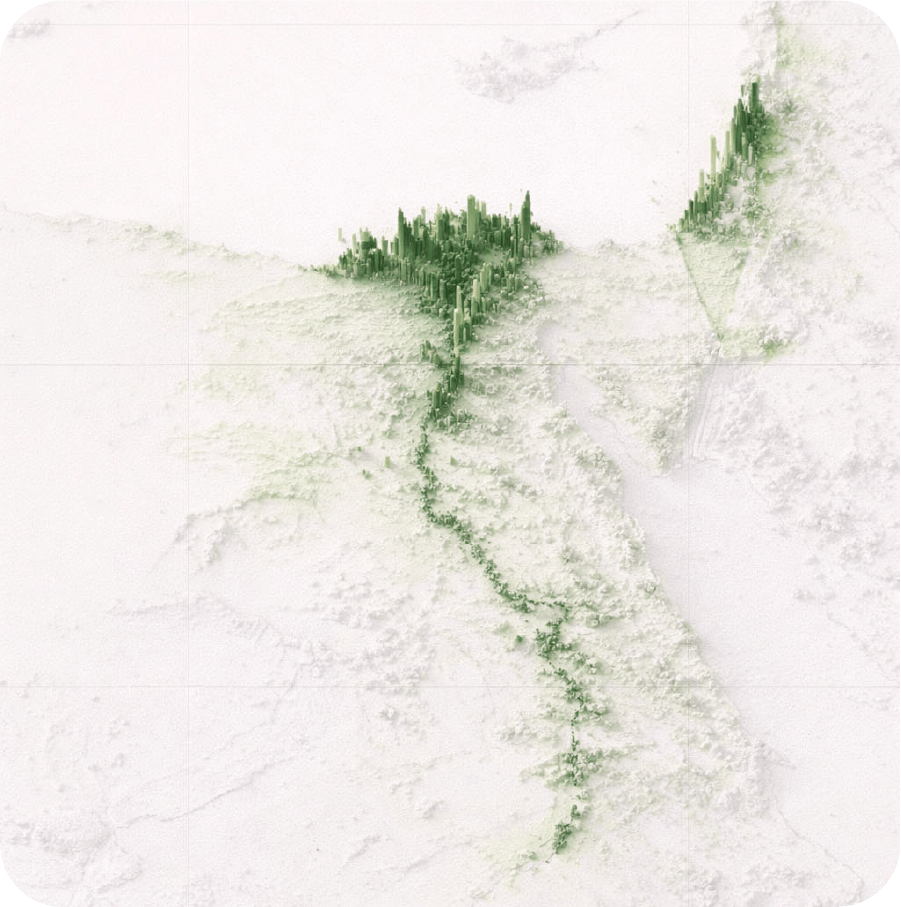

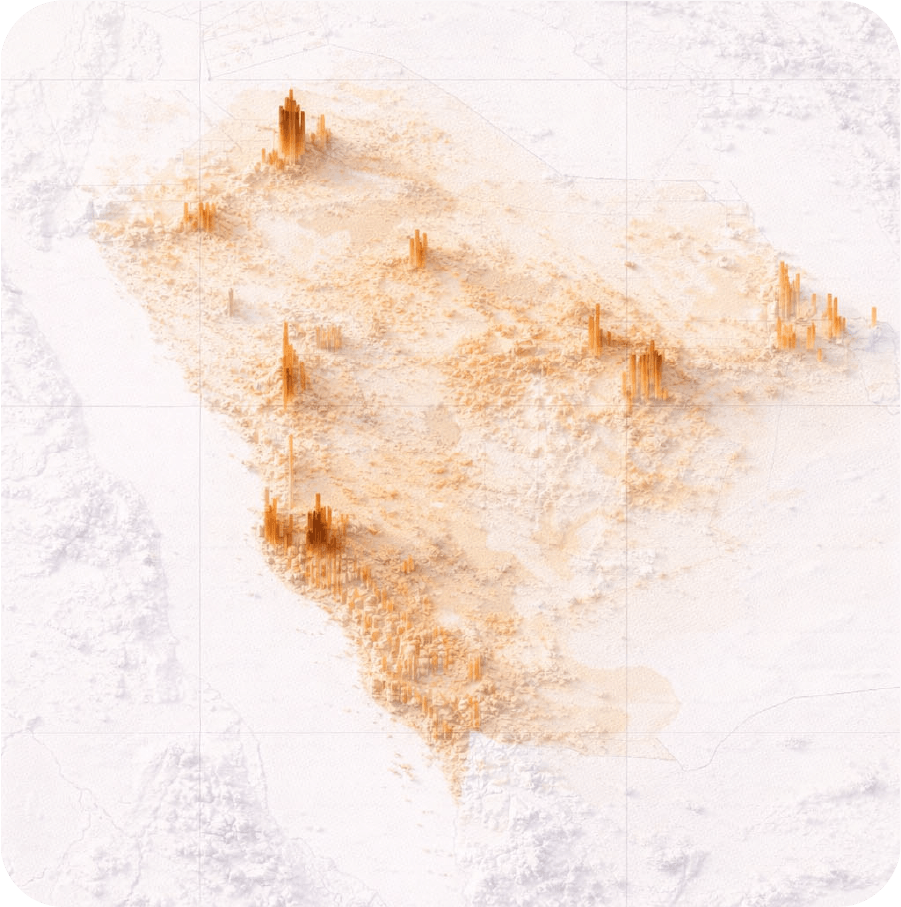

Lebanon is small—barely ten thousand square kilometers pressed between the Mediterranean and the Anti-Lebanon mountains. Yet within this compact geography exists extraordinary linguistic diversity. Lebanese Arabic—3ammiyya in local terminology—evolved at the crossroads of civilizations, religions, and empires. Before Arab conquest, this was Phoenician territory, then Aramaic-speaking. Crusaders left their mark, Ottomans ruled for four centuries, and France imposed a mandate for a quarter-century. Each layer left traces in the language Lebanese speak today.

The result is an Arabic variety that belongs firmly to the Levantine dialect group—sharing features with Syrian, Palestinian, and Jordanian Arabic—yet maintains its own distinctive character. It is perhaps the most accommodating dialect in the Arab world, absorbing foreign elements with remarkable ease. Where Saudi dialects preserve Classical purity and Moroccan Arabic evolved in relative isolation, Lebanese Arabic developed through constant negotiation with linguistic others.

The Weight of Earlier Tongues

The Echo of Aramaic

Before Arabic arrived in the seventh century, Aramaic was the lingua franca of the Levant. It left its deepest mark in religious vocabulary, where sectarian identities preserve ancient distinctions. The name for Jesus illustrates this perfectly. Lebanese Christians say yesu3 {jɛsuːʕ} يسوع, maintaining the Aramaic form yeshu3. Lebanese Muslims use 3issa {ʕiːsə} عيسى, the Arabic form found in the Quran. This is not merely linguistic preference but an identity marker—the word you use signals which religious community shaped your speech.

Ottoman Authority

Four centuries of Ottoman rule left Turkish loanwords throughout Lebanese vocabulary, particularly in domestic and administrative terminology.

The word for “room”—uudah {uːdə} أوضة from Turkish oda—competes with the Arabic-derived ghirfeh {ɣirfɛ} غِرْفِة. “Maybe” becomes barkeh {baːkɛ} بركِة or balkeh {bʌlk} بلكِة, from Turkish belkeh. “Lamp” is lumbah {lʌmbə} لمبة, borrowed from Turkish, which itself can be traced to Ancient Greek lampas.

These borrowings reveal more than vocabulary exchange. They show how power structures language—the administrative vocabulary of empire becomes the everyday speech of the governed, preserved long after empire falls.

The French Layer

The French Mandate (1920–1943) transformed Lebanon’s linguistic landscape in ways that persist today. French became the language of education for the elite, of administration, of cultural prestige. It left Lebanese Arabic saturated with French expressions that no longer feel foreign.

The most ubiquitous is merci, which has largely displaced Arabic shukran {ʃuːkrən} شكرا. Lebanese say merci kteerميرسي كتير (thanks a lot), seamlessly mixing French and Arabic. Bonjour بونجور replaced traditional greetings mar7abah {maːħʌbə} مرحبا or assalam alikom {əsʌlʌm ʕʌlaikɒm} السلام عليكم in many contexts. More remarkably, these French words undergo Arabic grammatical transformation. Bonjour takes Arabic possessive suffixes: bonjourak {bɒnʒuːrʌk} بونجورَك (good morning to you, masculine), bonjourik {bɒnʒuːriːk} بونجورِك (feminine), bonjourkon {bɒnʒuːrkon} بونجوركن (plural).

Other French terms are equally embedded: toilette تواليت for bathroom, piscine {piːsiːn} بيسين for swimming pool. The consonants /p/ and /v/, absent from other dialects of Arabic, appear exclusively in these foreign borrowings, expanding Lebanese phonetic inventory.

Lebanese Arabic sounds the way it does because it serves a society that values social connection intensely, that operates across multiple cultural and religious registers, that has learned to navigate difference as existential necessity.

The Sound of Simplification

Lebanese Arabic phonology reveals systematic simplification from Classical Arabic, driven by what might be called the principle of ease—speakers naturally gravitate toward sounds that require less articulatory effort and allow faster speech.

Consonants Transformed

| Classical Sound | MSA | Lebanese Urban | Lebanese Druze | Example |

| qāf (ق) | [q] deep uvular | [ʔ] glottal stop | [q] preserved | qalb قلب → alb ألب (heart) |

| jīm (ج) | [ʤ] | [ʒ] | [ʒ] | jamal جمل → (camel) |

| θ (ث) | [θ] as in “thing” | [t] | [t] | thalatha ثلاثة → tleteh تْلاته (three) |

| ð (ذ) | [ð] as in “this” | [d] | [d] | dhahab ذهب → dahab دهب (gold) |

Vowels Compressed

| Transformation | Classical | Lebanese | Driving Force |

| Long vowel fronting | kān كان [æ] (he was) | kēn [ɛ] | French/Ottoman front vowels |

| Short vowel deletion | katabtu كَتَبْتُ (I wrote) | ktabet كْتَبِت | Speed + urban intensity |

| min ayn من أين (where from) | mnen منين | Compression for efficiency | |

| Feminine ending | thalatha ثلاثة [ə] | tleteh تْلاته [ɛ] | Levantine marker |

For instance, Lebanese Arabic aggressively reduces vowels in unstressed syllables. Long vowels remain, but short vowels compress toward a schwa sound or disappear entirely. This compression reflects urban influence—French and Turkish, both languages with front vowels and reduced unstressed syllables—and the natural tendency toward faster speech in socially intense environments.

The result is that Lebanese Arabic sounds clipped, efficient, modern—phonetically distinct from the more open vowel patterns of Gulf dialects or the pharyngeal emphasis of Egyptian.

Lebanese Arabic also simplifies verb morphology dramatically from Modern Standard Arabic, creating structures optimized for conversational flow rather than grammatical precision.

Grammar for Speed

| Feature | Modern Standard Arabic | Lebanese Arabic | Function |

| Present tense | aktubu أكتب (I write) | bektob بكتب | b- prefix marks ongoing action |

| Present continuous | ana aktubu al-ān أنا أكتب الآن | 3am bektob عم بكتب (I’m writing) | 3am particle from Aramaic |

| Future | sa-aktubu سأكتب (I will write) | rah ektob رح اكتب | rah/7a/la7 particles (regional variants) |

| Plural address | antunna أنتنَ (you, feminine pl.) | entu إنتو (you all) | Gender-neutral, faster |

Furthermore, certain Lebanese lexical choices reveal the dialect’s distinctive character and its relationship to neighboring varieties.

Words That Reveal Identity

| Word/Expression | Lebanese | Regional Variants | Cultural Meaning |

| Please/Come in | tfaddal تفضّل | Used across Levantine | Embodies hospitality values: warm, polite, inviting |

| What | shu شو | Palestinian ash آشGulf wesh ويش | Different colonial/ethnic influences |

| To (preposition) | 3 ع3l maderseh عالمدرسة | Shared with Syrian, Jordanian, Palestinian | Levantine contraction for speed |

| Isn’t it right? | mahek ماهيك؟ | Syrian mou مو؟Jordanian msh sa7 hek مش صح هيك؟ | Merged form (ma + hek) = efficiency |

| Left | shmel شمال | Mostly Levantine: yasar يسار | Aramaic šmālā (left/north) preserved uniquely |

| Cat | bsayneh بسينة | Syrian attah أَطة | Exclusive Lebanese marker from Turkish pisi |

The Language of Encounter

Lebanese occupies a middle ground in Arabic’s linguistic landscape. It is neither the most conservative (that distinction belongs to Arabian Peninsula dialects) nor the most divergent (Moroccan claims that title). However, it is perhaps the most absorptive—the dialect most willing to incorporate foreign elements while maintaining Arabic grammatical core.

This reflects Lebanese history and sociology. Lebanon is a mosaic of religious communities—Maronite Christians, Sunni and Shia Muslims, Druze, Greek Orthodox, Armenian—each maintaining distinct identity while coexisting in compact geography. Survival required negotiation, accommodation, the ability to shift register depending on context. The language mirrors this: flexible, adaptive, comfortable with hybridity.

Urban Lebanese speech, particularly in Beirut, represents this accommodating character most clearly. French expressions integrate seamlessly. English increasingly penetrates youth vocabulary under the influence of American pop culture. Yet the grammatical structure remains Arabic, the core vocabulary remains Arabic, and phonetic patterns—however simplified—remain recognizably Levantine.

The result is a dialect that prioritizes communication over correctness, relationship over rule, efficiency over purity. Lebanese Arabic sounds the way it does because it serves a society that values social connection intensely, that operates across multiple cultural and religious registers, that has learned to navigate difference as existential necessity. This makes Lebanese Arabic sound modern without abandoning tradition, accessible without losing authenticity. The dialect carries warmth, humor, and social intelligence—qualities that formal Arabic suppresses. It reveals that linguistic creativity can emerge precisely from the space between languages. It is the conscious crafting of a vernacular that honors multiple inheritances while remaining unmistakably itself.

Rawali Habdulh

Translator and researcher

She is a translator and researcher with over ten years of experience in translation and interpretation. She is currently completing a Master of Research in Natural Language Processing at the Center for Language Sciences and Communication. Trilingual in English, Arabic, and French, she has worked as a freelance translator and interpreter with Australian clients and with Translators Without Borders. Her academic background in computational linguistics has strengthened her expertise in terminology analysis, lexicography, semantic modeling, and language technologies applied to machine-learning systems.