Language

Brazil: When Arabic Whispers in Portuguese

Some languages arrive through treaties. Others, through conquest. But there are rare languages that arrive carried by the soul—like Arabic did in Brazil. It didn’t come through official institutions, nor was it taught in schools by default. It arrived in the eyes of immigrants, in the cracked hands of merchants, in lullabies whispered at night, and in prayers murmured at dawn. Arabic did not come to Brazil as a visitor—it arrived as memory, as heritage, as longing.

It wasn’t just a language that was brought over—it was a culture, a rich and profound tradition, and a deep sense of connection to the land of the ancestors. In Brazil, Arabic didn’t simply survive; it thrived in the hearts of those who carried it across the oceans. It became part of the pulse, flowing through the veins of its people, adapting, evolving, and finding a place among other languages and cultures.

A Journey Across Oceans and Generations

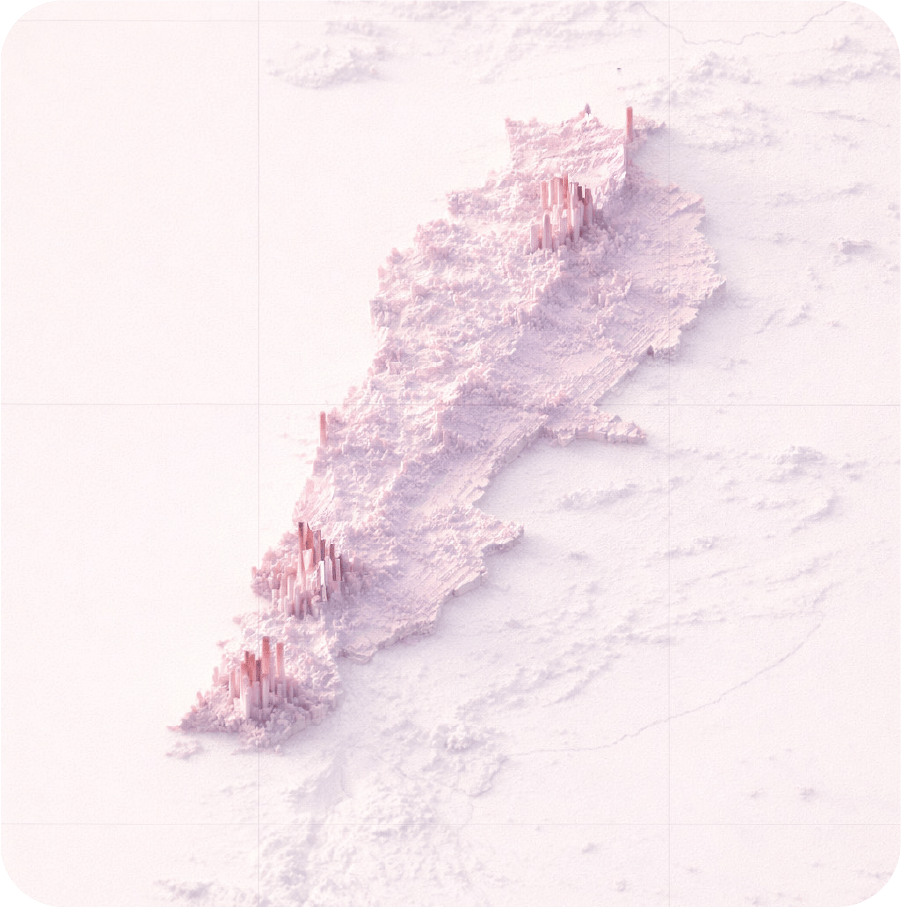

Since the late 19th century, waves of immigrants from Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine crossed the Atlantic seeking peace, hope, and new beginnings. They did not carry much in terms of possessions, but within their hearts, they carried centuries of culture, identity, and language.

As they settled in Brazil, they brought their language with them, speaking Arabic among themselves in homes, in marketplaces, and at gatherings. Today, it’s estimated that over ten million Brazilians are of Arab descent. While many may not speak Arabic fluently, the spirit of the language is still alive—in names, in recipes, in family values, and traditions. For many, Arabic became a bridge to the past—a way to stay connected to the stories of their ancestors.

However, the new generations of Arab Brazilians began to shift. They adapted, intermingled, and flourished in Brazilian society, becoming part of the very fabric of this diverse nation. They transformed Arabic into something uniquely Brazilian. For example, it is common to hear expressions like “Inshallah” (“If God wants/hopefully”) or “Yalla” (“Let’s go”) used informally within Arab Brazilian families. On the other hand, some Arabic words were reinterpreted or mixed with Portuguese constructions, such as using “habibi” (“darling/honey”) in affectionate ways not typical in standard dialects.

Arabic in Brazilian Life

In cities like São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Foz do Iguaçu, Arabic isn’t just a language—it’s part of the scenery. The call to prayer echoes softly from humble mosques. The scent of za’atar and cardamom wafts from family-run restaurants. Arabic calligraphy adorns walls and bookshelves. And in homes, the elderly still pass down poems, proverbs, and stories in the dialects of their grandparents.

Arabic has even left subtle traces on Brazilian Portuguese—for example, words like “açúcar” (from Arabic “al-sukkar”), “arroz” (from “aroz”), “almofada” (from “al-mukhadda”), “algodão” (from “al-qutn”), and “azulejo” (from “al-zulaij”) reflect Iberian-Arabic influence that arrived via Portuguese colonizers and was later reinforced culturally through Arab immigration. These are often unnoticed by speakers of the language, but they quietly testify to Arabic’s embedded legacy. Not just in vocabulary borrowed via Iberian influence, but in tone, rhythm, and the poetic, expressive way many Brazilians speak. Arabic, it seems, didn’t just bring words; it brought a way of speaking—warm, lyrical, and heartfelt.

Apart from pure language, Arabic has influenced Brazilian culture in profound ways. The sharing of food, music, and religious practices has allowed Arabic to flourish in Brazil. Families gather to prepare traditional Arabic dishes—from kibbeh to hummus, falafel, and baklava. These foods have become part of the Brazilian culinary landscape, just as Arabic words and phrases have become part of daily life.

What Kind of Arabic?

Arabic in Brazil is a mosaic. Most of the dialects spoken are Levantine—particularly Lebanese and Syrian—softened and reshaped over time by the cadence of Portuguese and the silence of distance. It is not uncommon to hear hybrid phrases where the two languages dance together.

For instance, some speakers say “Vou dar uma ma’assalama” when leaving, blending a Portuguese structure with the Arabic farewell “ma’assalama”. Others mix expressions like “Habibi, vamos al suq” (Darling, let’s go to the market), joining vocabulary and grammar from both languages into everyday speech.

Arabic, in this case, is not just the language of the past but also the language of the future—a key element in fostering economic prosperity and social cohesion.

Modern Standard Arabic, meanwhile, is mainly preserved in religious contexts, while dialects live on in families and community gatherings. More recently, there’s a growing interest in learning Arabic—not only among the descendants of immigrants, but also among Brazilians fascinated by its beauty and the cultural and commercial doors it opens.

The resurgence of Arabic in Brazil can be seen in educational institutions offering courses in the language. Arabic schools have sprouted in cities with large Arab populations, and even non-Arab Brazilians are enrolling in Arabic language classes, eager to learn about the culture that has so deeply influenced Brazil’s identity. The rise of Arabic literature being translated into Portuguese has also made Arabic more accessible to Brazilians, allowing them to connect with the profound legacy of Arabic-speaking societies.

A Powerful Language Can Build Bridges in Business

Specifically, in the realm of commerce, Arabic has become a strategic asset. Brazil is one of the world’s top exporters of halal meat and agricultural products to the Middle East. Knowing Arabic is not just a matter of making deals—it’s about building trust, showing respect, and creating lasting partnerships.

The Arab-Brazilian Chamber of Commerce plays a pivotal role in strengthening economic ties between Brazil and the Arab world. The organization works tirelessly to support businesses, facilitating trade in both directions and promoting the development of joint ventures. Arabic, in this case, is not just the language of the past but also the language of the future—a key element in fostering economic prosperity and social cohesion.

Beyond trade, Arabic plays a role in cultural diplomacy, academic exchange, tourism, and media. And as more Brazilians learn Arabic, it is becoming an even more powerful tool in fostering deeper connections with Arab countries.

A Living Language, a Beating Heart

Arabic in Brazil is not a frozen relic. Its presence in Brazil is a testament to the strength of human spirit—language’s ability to cross boundaries, to adapt, and to create something new and beautiful. In a world that often fractures along lines of difference, Arabic in Brazil gently reminds us that language can unify—and that identity is not defined by borders but by the love and connection we share with one another.

It’s more than a means of communication. It is a symbol of identity, a mark of endurance, and a quiet but powerful contributor to the Brazilian cultural landscape.

Arabic in Brazil is not just a part of the past; it is an essential piece of the future. As it continues to evolve, it will keep bridging the gaps between cultures, fostering mutual respect, and creating deeper connections between Brazil and the Arab world.

Houssam Nour Aldeen

Researcher, writer, and multilingual translator

Syrian-Brazilian researcher, writer, and multilingual translator with over eight years of experience translating between Arabic, Portuguese, and English. He holds a degree in Civil Engineering from Damascus University and a master’s degree in Construction Management. He also studied the origins of the Arabic language at Damascus University and conducted three academic research projects on the influence of Arabic on foreign cultures and languages. His work focuses on linguistic interaction, cultural exchange, and academic accuracy in international publications.

Pakistan: Religion, Migration, and Economic Ties

Linguistic Hybridity

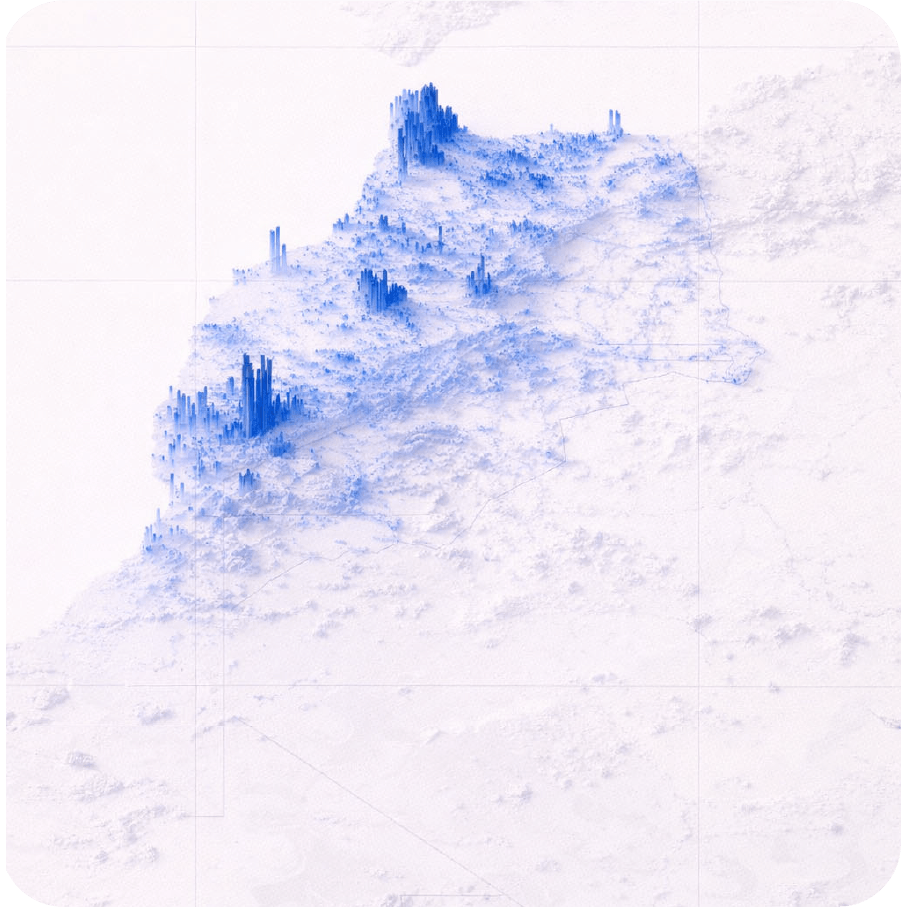

Although Arabic is not one of Pakistan’s official languages, it has a significant presence due to religious, educational, and migratory factors. The language has permeated Pakistani society primarily through religious and educational channels, as it forms the basis of Islamic rituals such as Quranic recitation, daily prayers, and religious terminology. Sharing the same scriptural framework as Urdu—including writing style and most of the alphabet—Arabic has also left a strong lexical imprint on everyday language use. Many Arabic terms, such as hukm, Sunnah, shariah, ilm, zakat, fiqh, and riba, are commonly used in Urdu.

While the number of fluent Arabic speakers in Pakistan remains relatively small—estimated at fewer than one million—the population with partial proficiency is considerably larger, mainly due to religious education. This group includes graduates of madrasahs (Islamic seminaries) and scholars who study Arabic as part of their religious training. Nationwide, more than 30,000 madrasahs incorporate Arabic into their curricula, producing approximately 30,000 to 40,000 Arabic-literate graduates each year. These institutions focus on Arabic grammar, syntax, and classical texts, fostering a level of proficiency among scholars and clerics that can be described as “religious Arabic.”

However, unlike the naturally evolved regional dialects spoken across the Arab world, the form of Arabic used in Pakistan is not a regional vernacular. It is a functional hybrid shaped by education, migration, and scriptural use. Spoken Arabic among Pakistani scholars is often marked by code-switching between Arabic, Urdu, and Persian, reflecting their educational backgrounds. As a result, this variety of Arabic tends to express a localized religious identity rather than an ethnic or native linguistic one.

Migration, Labor, and Tourism

Beyond religious education, Arabic is also present through expatriate communities and labor migration. Arabic-speaking expatriates—particularly from Gulf countries—form small but concentrated groups in major urban centers such as Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore. These communities are primarily involved in diplomacy, higher education, religious institutions, and business, and include diplomats, university students, and seminary teachers. Among Arab expatriates and returning migrants, spoken Arabic often retains elements of Gulf dialects, especially Saudi and Egyptian Arabic, reflecting the geographical origins of employers or host countries. Moreover, with over 2.5 million Pakistanis employed in Gulf nations, many returnees acquire practical proficiency in spoken Arabic; estimates suggest that around 15–20% of them possess functional language skills.

These skills are increasingly valuable in economic contexts. Arabic proficiency supports trade negotiations and facilitates access to key sectors such as halal food production, textiles, religious tourism, and religious publishing. In the halal certification industry, knowledge of Arabic is essential for ensuring compliance with religious standards and for building trust in Arab markets. Similarly, companies targeting Gulf countries often employ Arabic-speaking sales and customer support staff to improve communication and client retention.

Religious tourism further underscores the practical importance of Arabic. Hajj and Umrah travel to Saudi Arabia relies heavily on Arabic-speaking guides, administrators, and facilitators. At the same time, demand for Arabic expertise is growing in translation, media, and digital communication services, driven by the expansion of international content and cross-border communication.

Arabic extends beyond its traditional religious role, functioning as a contemporary medium for cross-cultural engagement, policy dialogue, and international business.

More broadly, the significance of Arabic is evident in Pakistan’s economic and cultural exchanges with Arab countries, particularly through labor migration and Islamic finance. As economic and cultural ties between Pakistan and the Arab world intensify—largely due to the rising economic power of Gulf economies—Arabic continues to gain importance. Remittances from Arabic-speaking countries account for nearly 58% of Pakistan’s total remittance inflows, underscoring both economic dependence and strong cultural connections. In the Islamic finance sector, which represents over 20.5% of Pakistan’s banking assets, Arabic proficiency is crucial: Professionals must understand Arabic legal terminology, fatwas, and Shariah jurisprudence. Consequently, Islamic banks and related institutions actively seek candidates who can read Arabic for compliance and advisory roles. This trend aligns with global patterns, as organizations offering Shariah-compliant services increasingly prioritize Arabic-speaking professionals. Likewise, logistics and freight-forwarding firms working with GCC countries value Arabic proficiency for coordination and documentation.

Beyond a Traditional Role

Globally, over 1.8 billion Muslims engage with Arabic as part of their religious practices. At the same time, the growing political and economic influence of countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar—whose combined sovereign wealth exceeds $2 trillion—has fueled worldwide demand for Arabic-speaking professionals and cultural expertise. In this context, Arabic extends beyond its traditional religious role, functioning as a contemporary medium for cross-cultural engagement, policy dialogue, and international business. Its reach has expanded alongside the increasing influence of Arab nations in trade, diplomacy, energy, and global governance.

In conclusion, although Arabic is not an official language in Pakistan, it holds substantial religious, educational, and economic significance. It functions both as a cultural cornerstone and as a practical tool for collaboration with Arab countries, enabling access to international networks, strategic markets, and cross-border partnerships. The growing presence of Arabic in media, academia, and diplomatic settings also points to its expanding soft power. In Pakistan, Arabic occupies a distinctive linguistic and cultural position—rooted in religious scholarship, reinforced by labor migration, and increasingly shaped by economic and social dynamics.

While it cannot be considered an indigenous language, its sustained role in education and religious life, together with deepening economic ties with the Arab world, ensures that Arabic remains a language of considerable prestige and utility. Ultimately, Arabic serves as a cultural and ideological bridge connecting Pakistan to the broader Arab-Islamic world, opening avenues for further educational, economic, and professional collaboration on a global scale.

Muhammad Luqman

Islamic scholar, researcher, and multilingual translator

Muhammad Luqman holds an MS/MPhil degree in Islamic Finance and an eight-year degree in Islamic Theology. He has also completed translation and certification courses in several languages. He specializes in Islamic curriculum and content development, fiqh texts, and Shariah-compliant finance. He is a dedicated Islamic scholar, researcher, and multilingual translator with over seven years of experience in Islamic academia, content development, and translation. His work integrates traditional Islamic scholarship with modern academic frameworks to produce authentic, well-researched, and accessible content for books, curricula, research papers, and institutional publications.

Indonesia: The Language of Coexistence

Identities in Transition

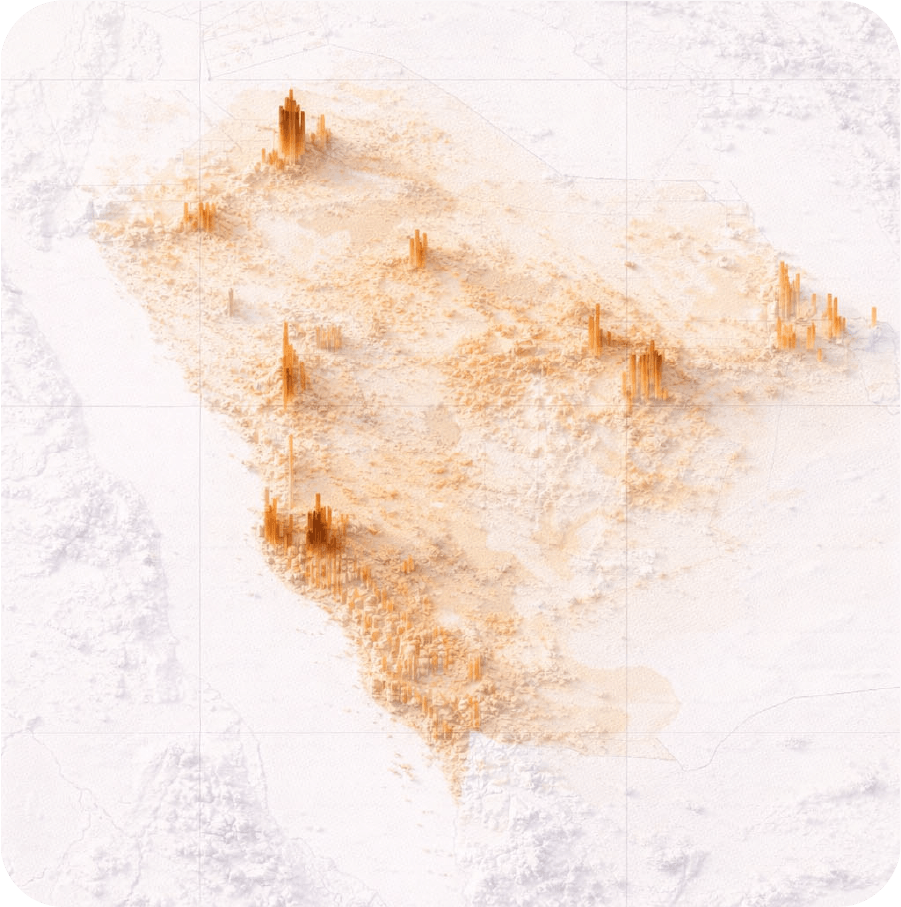

Arabs are believed to have arrived in Indonesia centuries ago, and several theories have been proposed regarding their initial presence. One of the earliest records dates back to 674 AD, written by a Chinese merchant who documented the existence of an Arabian-Muslim settlement along the western coast of Sumatra. According to this account, Arabs had assimilated into local society through intermarriage, forming communities in which Arabs and locals lived side by side.

Another influential explanation, known as the Gujarat theory and advanced by Dutch scholars such as J. Pijnappel, Snouck Hurgronje, W. F. Stutterheim, and J. P. Moquette, suggests that Arab migrants first settled in southern India before traveling to Indonesia for trade. Over time, the spread of Arabian-Muslim merchants and scholars across the archipelago, together with the establishment of Islamic sultanates such as Perlak (840 AD, later merged with Samudra Pasai in 1292), Samudra Pasai (1267–1521), and Aceh (1496–1903), further consolidated Arab presence in the region.

Today, however, the exact number of Arab descendants in Indonesia is difficult to determine. Centuries of integration have produced hybrid identities: while many Indonesians have Arab ancestry, this does not necessarily mean they speak Arabic as a mother tongue. At the same time, Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) have made Arabic a mandatory subject, taught as a gateway to broader Islamic studies. As a result, many Indonesians without Arab ancestry acquire Arabic proficiency. This dynamic makes ancestry less relevant when considering who can be classified as an “Arabic speaker” in Indonesia, as santri (students of pesantren, most of whom are locals) often demonstrate strong reading comprehension and speaking abilities in Arabic.

With its long history, Arabic has become deeply embedded in Indonesian society—and in the Indonesian language itself. It was initially introduced through Islamic teachings (majlis taklim) led by scholars from Arab-descendant families, mixed-heritage backgrounds, or indigenous communities who had studied Arabic and Islamic sciences. As Arabic served as the primary medium for accessing Islamic knowledge, it became inseparable from religious life.

The expansion of Islam throughout the archipelago further institutionalized Arabic through the establishment of pesantren and Islamic schools (madrasah), particularly from the early 20th century onward. As an alumnus of a pesantren with connections to graduates from various institutions across Indonesia, it is evident that santri and Islamic scholars often develop fluency in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). This proficiency is reinforced through sustained engagement with classical Arabic texts that have been studied and transmitted for generations.

Linguistic Blend

As Islam became the country’s dominant religion, Arabic moved closer to everyday society, contributing to a process of linguistic integration. Indonesian developed through extensive code-mixing, incorporating elements not only from Arabic but also from languages introduced by colonial and occupying powers, including Dutch, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Japanese. Arabic loanwords are particularly prominent: terms such as kursi (chair), majlis (forum), dewan (board), and even the names of the days of the week (Senin, Selasa, Rabu, Kamis, Jumat, Sabtu) are derived from Arabic. Studies by Russell Jones (1978; 2007) estimate that Indonesian contains at least 2,750 Arabic loanwords, rising to over 3,000 when derivations are included, out of approximately 208,283 entries in Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia. By comparison, Malay—Indonesian’s closest linguistic relative—contains around 1,791 Arabic loanwords out of 28,000 entries in Kamus Dewan.

Centuries of integration have produced hybrid identities. Among santri, it is not uncommon to speak Arabic using Indonesian syntactic patterns—a variety often referred to as Arab Pondok.

In everyday practice, Arabic has not developed into a distinct regional dialect in Indonesia. This is largely due to the structural differences between Indonesian and Arabic, as well as the predominance of MSA as the most commonly taught form. However, among santri, it is not uncommon to speak Arabic using Indonesian syntactic patterns—a variety often referred to as Arab Pondok. For instance, expressions such as “ماذا ماذا ال” are used to mean tidak apa-apa (“no problem”), whereas the correct Arabic expression would be “لا بأس”. This form of Arabic remains largely confined to educational environments and does not replace MSA as the primary linguistic reference.

By contrast, some Arab-descendant communities continue to use Yemeni Arabic in informal settings, a practice passed down through generations, as many trace their origins to the Hadramaut region of Yemen. In interactions with the wider population, however, Indonesian remains the dominant language.

Arabic and Business in Indonesia

The economic role of Arab communities in Indonesia dates back to the colonial era. Hadhrami Arabs, many of whom migrated from Yemen, were particularly active in commerce, property, and hospitality. By the 19th century, they had established themselves as influential entrepreneurs in port cities such as Surabaya and Batavia (now Jakarta), owning warehouses, shops, and hotels. Their fluency in Arabic supported both religious practice and commercial activity, functioning as cultural capital within transnational trade networks and diaspora communities.

Today, this legacy is especially visible in the culinary sector. Middle Eastern restaurants—particularly those specializing in Yemeni cuisine, such as the well-known Al Jazeerah Signature in Jakarta—have become established culinary landmarks. More than 200 Arab restaurants currently operate across Indonesia, reflecting sustained interest in Middle Eastern food culture.

In infrastructure and diplomacy, the Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ) Elevated Toll Road illustrates the growing ties between Indonesia and the Arab world. Officially inaugurated in December 2019 and renamed in April 2021, the 36.4-kilometer toll road functions not only as a key transportation route but also as a symbolic marker of strengthening bilateral relations between Indonesia and the United Arab Emirates.

Arab business communities continue to maintain active professional networks. Organizations such as the Indonesia Arab Business Forum provide platforms for collaboration, knowledge exchange, and entrepreneurship. Young figures like Adil Abdul Manief Makki—a Saudi national with Indonesian heritage—exemplify how the Arab diaspora remains a dynamic force in shaping Indonesia’s contemporary business landscape.

This long-standing economic presence highlights the value of Arabic beyond religious and educational contexts. For entrepreneurs, educators, and professionals engaging with Arab partners or institutions, Arabic proficiency offers a competitive advantage, granting access to opportunities rooted in historical connections and reinforced by modern international cooperation.

Conclusion

From early settlements along the western coast of Sumatra to present-day business corridors in Indonesia’s major cities, the Arabic language and Arab communities have left a lasting imprint on the country’s social and economic fabric. While Arabic is not an official language, its influence extends far beyond religious practice. Through centuries of integration, education, and entrepreneurship, Arabic has shaped linguistic patterns, academic institutions, and contemporary commercial dynamics—from pesantren classrooms to culinary enterprises and large-scale infrastructure projects involving Gulf partners.

As Indonesia continues to deepen its ties with Arab countries, particularly in trade and diplomacy, Arabic proficiency and cultural literacy are likely to become increasingly strategic assets, bridging not only historical relationships but also future possibilities. Understanding Arabic in Indonesia, therefore, is not merely a linguistic exercise but a lens through which to examine diasporic identity, intergenerational adaptation, and global connectivity.

Bintang Purwanda

Freelance translator and linguist

Bintang Purwanda is a freelance translator and linguist with over a decade of experience working with English, Arabic, Indonesian, and Malay. In addition to his translation work, he actively pursues writing and research, reflecting his broader interest in language and cultural studies.