Localization

Ultralocalization, indigenous languages, education, and the role of governments: discover the main topics discussed at the Imminent Unconference in Punta del Este.

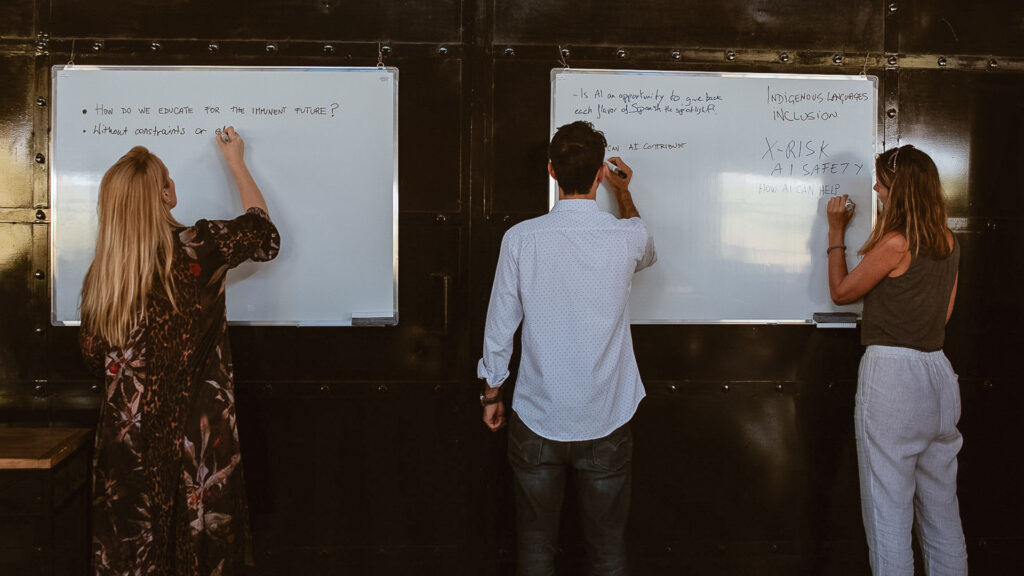

Punta del Este, 15 February. Twenty-five language senior professionals and experts from the Americas and Europe gathered in Uruguay in an unconference to discuss the challenges that South America faces today and discover what needs to be done for AI to have a brighter future in the language industry.

The Imminent Unconference is a platform and a space for debate powered by Translated. This Unconference was held in Punta del Este, one of the docking ports of the Ocean Globe Race, to which Translated is participating with the boat Translated-9 and where the sailors can only use the technology that was available 50 years ago to sail across the oceans. This project provided Translated with the perfect metaphor to convey one message: we believe in humans.

The participants proposed several topics within the main premise, and these were summed up in four categories: education, government, indigenous languages and the importance of South America and its variants.

1. The challenge of ultralocalization: why should we care about the variants of Spanish in South America?

When people think of South America, what languages come instantly to mind? Spanish and Portuguese. However, do South Americans speak the same Spanish? Do they all belong to the same linguistic block? Are companies targeting Spanish unique variants or are they just reaching audiences in a “neutral” Spanish? Will the advances of AI finally bring an opportunity to treat each variant as it deserves?

South American Spanish is full of flavors, for that reason, to say that there is only “vanilla” would be an understatement. “Vanilla” Spanish is just one broad generic flavor used by most companies to localize. Not only that, but they usually do it using one type of variant (mostly Mexican Spanish) as a starting point and the entire Spanish speaking community falls under one homogenous “neutral vanilla” Spanish.

Alas, since neutral Spanish has been around for so long, Latin America has grown very used to it. Is this a problem of localization or is it simply a matter of where the main content comes from? Companies have a role in this, and they could have an impact if they were interested in accessing certain specific markets. The most conspicuous example of the dominance of neutral Spanish can be seen in children. They consume it every day on TV, and they use it in their everyday life as well. The more television they watch, the more they speak it, slowly losing their unique variant. Are speakers of other variants okay with that? Some argue that this does not represent a problem for the parents because TV is only one portion of what they consume. The Rioplatense variant is significantly different from other Spanish variants (the voseo and the yeísmo are the most prominent features), but Uruguayans and Argentinians are so accustomed to consuming content in neutral Spanish that if they were specifically targeted and the content were ultralocalized to Rioplatense it would come as a shock, and they might even reject it.

The decision to ultralocalize depends highly on the content, the product and the company’s goals and vision. For products where user experience is essential, companies go the extra mile and take the initial “vanilla” Spanish and adapt it to the different variants, one per country. In campaign ads, for instance, where marketing and culture are involved, variants are used to create a stronger emotional connection with the audience, and specific words of specific variants are a must. In products where people are used to seeing a neutral Spanish, localization would not make a difference in terms of gaining more followers or consumers, but it would definitely make them feel better about the experience. Another aspect to consider are costs. If a company is determined to make a “magical user experience,” the costs for making an ultralocalized version of the content are not very high and it might eventually end up in a bigger return on investment. But when budgets are too tight, to localize into variants is not a priority, as it is assumed that Spanish speakers will accept this “vanilla” Spanish and buy the product anyway.

In which ways could AI help localize these variants? Currently, LLMs learn reality from the English model, and this poses a challenge for the cultural aspects. Because of its lack of insight into the cultures, issues have to be solved either through data or other techniques. The technological advancements in AI could be a great opportunity to train LLMs that do not have a lot of data for certain variants, and combined with a database of information, it could yield good results. This could be applied, for instance, to Paraguay, which does not have a lot of data to work from. In other countries such as Mexico, Argentina, and Chile, such sophisticated technology is not necessary; the process can be easily done using machine translation.

From the companies’ viewpoint, to include variants is not that expensive, and it will ensure a better user experience. Even though the return on investment cannot be immediately measured, if the resources are there, it is the best path to choose, and the data will come eventually. In some companies, localizing into one variant per country proved to be statistically significant and it improved the user engagement. Localizing can also be considered as a way of preventing competition. Today, a product may not have a lot of competitors in a certain region, but it might happen that local start-ups enter the market with already localized products and with its eventual growth it might force the competition to step up.

The matter is also educational. An average person from the global North does not know that South America is full of Spanish variants or that for Uruguayans, championes is the word for sneakers and zapatillas is the one for Argentina, or that alberca is mostly used in Mexico to refer to a swimming pool but piscina and pileta are used in Argentina and Uruguay.

In the modern era, businesses can no longer use profits as their sole parameter to measure success. If decisions are made this way, they are not seeing the bigger picture. Would it not be a great opportunity for companies to focus more on their specific targets and make the user feel their identity is being respected? After all, language is a synonym of identity and culture. If we slowly lose interest in our variants, would it not also mean we are losing interest in our identity?

2. How can AI enhance education? From training a generation of tech-focused localizers to helping people with disabilities.

Is it possible to modify the curricula of translation majors to prepare a generation of tech-focused localizers in South America?

As modern technologies such as machine translation and AI continue to develop, translators’ roles are changing, and South American universities do not seem to keep up with this process. Professional linguists obtain their degree, but the programs usually do not have courses that focus on technology or localization. This certainly has an impact on the process of hiring graduates who sadly do not have the relevant tools required by companies today. This reality poses an important question: Is there a plan to standardize the way professionals are trained?

Plenty of students and graduates complain that university programs do not give them the proper training to meet the needs of the translation and localization industry. Most companies have been filling that technological gap by training their new employees, given that the same strategy showed good results with project managers. The dynamic of the teams is changing, as the language industry suggests that in the future, translators will revise and edit the translation made by AI. This means that translators need to change their mindset, but they also need to know that AI will not replace nor compete with them. This new technology will change the profession as we know it today, and it will also improve their productivity.

There is evidence that the majority of universities in South America are teaching the same translation programs that they have been teaching for 20 years. However, there are institutions in Spain and the United States that are trying to keep up with the needs of the language industry even though they find it difficult because technology evolves extremely fast. Not only do South American universities need to consider adding technology tools and localization training in their programs, but they also should consider offering constant retraining as other professionals such as doctors and teachers get.

At the moment, there are companies which are benefitting from the shortcomings of South American universities. These companies have developed different courses to cover the training that translation programs do not provide and they charge low fees to create an attractive offer. This is the current solution translators and language companies are choosing to keep up with the fast pace of translation technology development.

Can AI be the superpower of people with disabilities?

People with disabilities such as blindness, hearing loss or deafness face big barriers every day when it comes to communication. One of the main questions posed in this session was: Is AI available for those who cannot see or hear and indubitably need to understand and be understood by others? What happens with deaf people who cannot write in another language and therefore cannot transmit even a simple idea to their interlocutor? Can AI help them?

The truth is that we do not usually create technology for deaf people, and people without disabilities usually are not aware of the issues they face and, therefore, do not learn how to communicate with them. It is easy to see that on airplanes, schools, or elevators. When a deaf person travels by plane, they do not receive safety instructions in sign language, hence, they only receive part of the information. Furthermore, in case of an emergency, they will know that they need to fasten their seatbelts if the seatbelt light is on, but they will not know why, because they cannot hear the pilot’s explanation. They have to check the other passengers’ expressions and try to understand what the situation is. It must be terrifying.

One of the solutions would be to educate the community so they can communicate with them in the way they already do. In Uruguay there is a project which intends to help people learn sign language with AI. There is also a company in the United States that created a digital human that uses its hands, face, eyebrows, and mouth to provide a more comprehensive form of communication to its clients. This is a difficult process due to the attention to detail it requires, but it is definitely the path every company should follow. As a society, we need to understand that nowadays we have more tools to work on this and help disabled people feel part of the community and not excluded as it often happens.

Another way to solve this communication barrier could be a device that helps them communicate. Said device could have a number of settings (visual, haptic and others) so when a disabled person needs to interact with someone, their system will transmit the message to the other person and vice versa. At first, these devices might not be affordable for everyone, but as new companies start making their own, there will be a price competition as it happened with cell phones. The better the AI and technology get, the more people will engage in using it.

Education on the importance of finding a real communication channel for everyone is vital. The government and the education institutions will play a key role in spreading awareness and the knowledge of AI, as well as in developing the necessary tools. However, it is also essential to remember the phrase “Nothing about us without us” by James Charlton. We need to listen carefully to the disabled people in order to understand what they need and what they believe will be the best way to solve their difficulties. We need to focus on knowing and accepting the diversity and adapt to the language system that already exists. And lastly, the individual effort must not be forgotten. We need to educate, make these issues visible, learn and use the technology to share its benefits with others.

3. Should governments control the development of AI and language? To what extent?

One of the various problems that governments have to deal with is the lack and misuse of modern technology. The existing national and international regulations are not quite adjusted to the technology that we have in 2024. There are exceptions, but in general, governments do not have the knowledge nor the tools to accompany technological advancement with its legislation. A clear example of what is happening in South America is Argentina. Their government does not have the tools, nor does it count on IT experts who can help with that because they are either working overseas or working for a foreign company. A few weeks ago, there were plenty of AFIP [Argentina’s tax agency] users affected as they were hacked, and 82,000 passwords were leaked on the dark web. This is not the first time hackers have leaked sensitive government data. In short, the government does now know how to control harmful technology and AI in general, mainly because they do not have the knowledge and they do not know what they really need to control.

What role does social media play in South Americans’ everyday life?

In the United States, the major contributor for controlling AI is the fact that fake AI can control the narrative of politics, among other things. People use AI to create untruthful content and it spreads through social media making people believe things that are not necessarily true. In the rest of the world, we can see that not only is it affecting the politics narrative, but it is also affecting the entertainment industry. For instance, the new president of Argentina, Javier Milei won the elections in November 2023 after doing his political campaign mostly through social media. In Chile, a producer used AI to create a song using the voices of three different artists without their consent, but one of them found out that the song had thousands of reproductions on Spotify. The questions that arise in this case are: Who is the owner of the song? Can these artists sue the producer? Are there specific regulations to solve this problem?

Businesspeople are using avatars to make presentations around the world to present their products in languages they have never spoken and that is a great opportunity that they did not have before. However, people are being harmed and deceived by this new technology in other areas. There have been growing concerns about AI safety and governments have started making efforts to respond to the demands of AI regulation. Brazil is one of the countries which is examining a bill related to the use of AI. This discussion started in 2023 in the Brazilian Congress and is extremely important as Brazilians will have elections this year and the government wants to ensure democracy for their citizens. Social media and AI are powerful and useful as well as dangerous tools if not used properly.

How does the government help and limit AI users?

There have been a few cases in which a company or a government has banned the use of machine translation or AI technology as they were concerned about future consequences should there be a serious mistake or bad intentions by its users. Managing and misusing personal data as well as providing adult content to minors and even creating child pornography are enough reasons for the governments to consider updating their laws to avoid legal loopholes regarding the AI technology.

One of the government’s most important roles is the protection of its citizens. The ever-improving technological advances have been extremely helpful for this purpose. For instance, the development of facial recognition has helped make arrests and avert tragedies. However, the emergence of new technologies brings along concerns regarding the morality, safety, privacy and impact of its application. And it is also true that legislation lags far behind these advancements and that it usually takes a catastrophic event before any relevant law is passed.

It is clear that there needs to be a balance between the restrictions imposed by the government to protect its citizens, and the limitations that can curtail the progress of AI. South American governments can play a key role in the development of AI and Large Language Models (LLM) by investing both in the public and private sectors. Governments have the resources for investing where private companies often cannot or will not because of high costs, and these technologies can be privatized later on in their development. Governments can also create an environment that incentivizes and protects professionals that are making advances in these technologies.

4. How to include AI in the indigenous languages of South America?

In a globalized world where technology advances by leaps and bounds every day, is everyone included in this progress? South America has over 800 Indigenous Peoples which make up a total of over 50 million inhabitants, and an estimated 560 Indigenous languages are spoken. Are they prepared to access AI? Are they interested in getting involved with it? Is it possible to include Indigenous languages in AI? The short answer is: Yes. But depending on the techniques and technology used in the process, it might take a great deal of time, research and resources. The decision to include Indigenous languages into these processes is usually made across three levels: at a community level, at a government level, and at a business level.

Community Level

The community might not want to have their dialect included in LLMs. Not every Indigenous community is interested in using technology; some of them are very apprehensive when it comes to this topic and especially since it strikes a sensitive chord: language. Oral language is a vital element in their community and it is one of the means they have to keep their culture alive and pass it on to future generations. Some communities are already deeply involved with technology; they embrace it, and are excited about new advancements. The Quechua community—the largest one in South America in terms of inhabitants—are owners of big companies, and use technology to do business. Despite their openness, the way they are approached is essential. Some may take this approach as a synonym of colonization, and are not willing to let anyone interfere in the language they own. The motto “nothing about us without us,” applies to this situation as well. When Indigenous communities get involved in the process of data collection to train LLMs and get to see the final output, they feel that they are more than simple data providers. The Mapuche, the largest Indigenous community in Chile, filed a lawsuit against Microsoft in 2006 when they launched a language package in Mapuzugun, one of their languages. This community stated that they were the ones who owned and controlled their language, and that Microsoft had not asked for their permission to do this, nor had they been asked to get involved in the process. All of this also sparked the debate of whether a language can be owned.

Government Level

The decision may come from governments. When a company wants to access a certain market and the government requires that for it to operate in a specific region, the content has to be translated into every language and dialect spoken in said region, then it is a matter of compliance, and companies will oblige. Because of this, large companies like Microsoft, for instance, have translated their content into Quechua, Aymara, Guarani, and K’iche’.

Business Level

The decision may come from businesses. What happens most of the time is that companies (if they don’t have to comply) only translate their content into the main language of a country, and other languages are left behind. Indigenous communities usually also speak the main language of the country, but with the evolution of AI it would be a good opportunity to have their content translated into their dialect and not be “forced” to read in a language that is not their own. Aside from the fact that it is ultimately the community’s decision, a hurdle to overcome is the lack of data. Currently, GPT4 is being trained with 7 trillion words in English, 1 trillion in Spanish and 1 trillion in French and the rest decreases proportionally to the amount of data; the more data, the better the quality of the language, which is the case for the top ten languages spoken in the world. What about Indigenous languages? If there is not enough data, then the task could be colossal. It is believed that if LLMs are trained with intelligence (human intelligence, that is) combined with data, in a few years’ time the task would be feasible. This technique would not only help make a faster progress, but it would also be a way of doing it while preserving the culture, since MT combined with human intelligence could provide results that are more culturally sensitive than the ones available now. Because data is a limiting factor, the output may not be perfect if compared with the top ten languages results, but at least, Indigenous communities could get some access to this technology, and they could create more sources of income for their people. The gap that AI is generating in this already globalized world could become wider for these communities if they are left behind in this ever-changing advance. Another constraining factor is cost. The possible linguistic combinations are vast, because it is not just about Spanish or English into Quechua, it is also about Quechua into Aymara, Guaraní into French, and so on. Therefore, the costs to train the machine may be too high to include all of them and create a decent model.

Another issue is that these languages are oral, and illiteracy is very high among these communities. For that reason, voice technology might be vital to get the necessary data and provide a solution to access. Through this technology, a lot of term bases could be created and that could be the starting point to train LLMs.

To sum up, a lot of work still needs to be done. Policies need to be improved, technologies as well, and a lot more conversations need to be had in companies as to why it is important to include Indigenous languages in technologies. If these communities are included, it is a way of showing that everyone cares about them, that the aim is not to colonize or to take over their culture. It is actually a matter of social impact and an act of love. The question that remains is: will they want to? If they do, would they be okay with the fact that it may not be perfect due to the lack of data? Is an imperfect LLM better than none? Every community is at a different level in terms of interest and inclusion, so it is not easy to reach a conclusion on this topic. The line between colonization and providing access and opportunities is a very thin one, so where that line is drawn is very challenging. potential for growth. South Americans care about their identity, but a shift in the mindset is needed, not only in the global North but also in South America itself. Indigenous languages, provided they want to open up more to globalization, should be included in the technological advances, but always taking into account their decision to do it and getting them involved in the entire process.

The article was co-written by the Imminent Unconference notetakers Micaela De Fino and Florencia Olivera.

Micaela De Fino is a Certified English to Spanish Translator graduated from Universidad de la República, and specializes in legal and medical translation. Since 2020, she has worked for national and international clients, translating diverse academic, financial and corporate documents as well as medical journals for publishing. Micaela has interpreted at CASMU Hospital and worked on the subtitling for the series Golazo and the short film Raíces en la arena. She is passionate about bridging cultures and enjoys using her skills to connect people through language.

Florencia Olivera is an English to Spanish (LatAm) freelance translator based in Uruguay specialized in legal, marketing and SEO content translation and localization. She graduated as a Sworn Translator from Universidad de la República in 2018. Since then, sha has been dedicated to helping companies and brands communicate to their Spanish-speaking audience by translating their content accurately and effectively, always striving for high quality work. I have a diverse client portfolio which includes international translation agencies, luxury products brands, advertising agencies, NGOs, and travel and leisure companies, among others.