Localization

Why does building a more inclusive future in the world of communication require a collective creative effort? Why should we strive for a global communication paradigm reset? Why should we eschew political correctness in favor of new representations and narratives? Why does localization play a key role in the process of building a more inclusive future?

These are some of the questions that prompted me to reflect on the theme of inclusion and how creativity is partially responsible for helping to design a truly inclusive future capable of embracing all individuals and their respective communities. Communication, entertainment, and design address the theme of inclusion from different perspectives but have one thing in common: they speak to the same people with their uniqueness, identity, and history.

Addressing the issue of representation and inclusion certainly means providing answers, but before all else, it means starting to ask the right questions. But when? Not at the tail end of the creative, communication, and design processes when the only remedy for an idea that hurts someone is to kill it. It means asking yourself the questions before you start thinking creatively. Why would you exclude someone with a purpose?

In other words, you should examine yourself and your message. Imagine your target audience, and reflect on whether the concept may be deliberately or unintentionally excluding specific identity groups. If that is the case, the follow-up question is whether that exclusion is actually necessary.

Concepts that avoid actively excluding communities have the potential to showcase different cultures and contribute to global discourse. As the history of inclusive design shows, if you incorporate inclusion from the beginning, you will obtain a better product, service, or experience.

We will analyze the new role of brands in contemporary society and see how inclusion is an identitarian and multicultural issue that impacts workforce relations, creativity, and representation in the communication, entertainment, and design domains. We shall define what this means for the world of localization, hypothesizing a shared working approach through which we, too, can contribute to building a more inclusive future for all. And if we truly believe in the value of every individual – “We believe in humans” – we must work to ensure that everyone, in their own right, can feel “part of our community”.

“What do we expect from brands in the contemporary world?”

“This means that brands, who are nothing without their communities, will make the radical move from being sellers to coordinators. To genuinely place collectivism at the heart of their products, campaigns, and workforces, brands should prepare for a future in which they invite customers to run their busi- nesses, design infrastructure as a service, and blur the boundaries between a company, a community, and a collective.” (LSN Global)

In other words, not only will brands be empowered to prioritize inclusivity in their communication, but they will be actively called upon to value diversity and acknowledge its universal valence.

For brands, inclusiveness will demand more than merely countering exclusion; it will mean enhancing the value of the uniqueness of disparate communities and intimately connecting with them. Communities have been a lifeline for groups that have historically been excluded from mainstream society. The ZAlpha generation – where Z and Alpha generations intersect – will be the most diverse ever. The number of white Americans has declined for the first time in history, and one in six young people in the United States identifies as LGBTQIA+. We can expect community values to play a central role in our future society. (sources: US Census Bureau, Gallup).

“Take young Hispanics as an example: they are well aware that marketing has failed to capture the diversity of their demographic group. This consumer segment includes first-, second-, and third-generation Americans from more than 20 countries. Hispanics comprise Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, and Cuban-Americans: two different cultures coming together. Hispanic youth are also rethinking the language of their identity, with many preferring gender-inclusive terms like Latinx over Hispanic and Latino. But with just 3% of this group calling themselves Latinx, we can expect the younger generation to implement this fluid change in the years ahead (Pew Research Center).” Via LSN Global

Brands have a new role as community coordinators, and as such, the collective creative intelligence they are able to activate will be what makes them successful.

The hyper-individualistic narrative conveyed by social media might lead one to think of an ego-driven future; conversely, the Zalpha generation is dispelling this myth, recognizing that collaborative thinking is essential for a better future.

Alliances built online around common interests have become squads in venues like Discord and Bilibili, transforming the way we connect and collaborate.

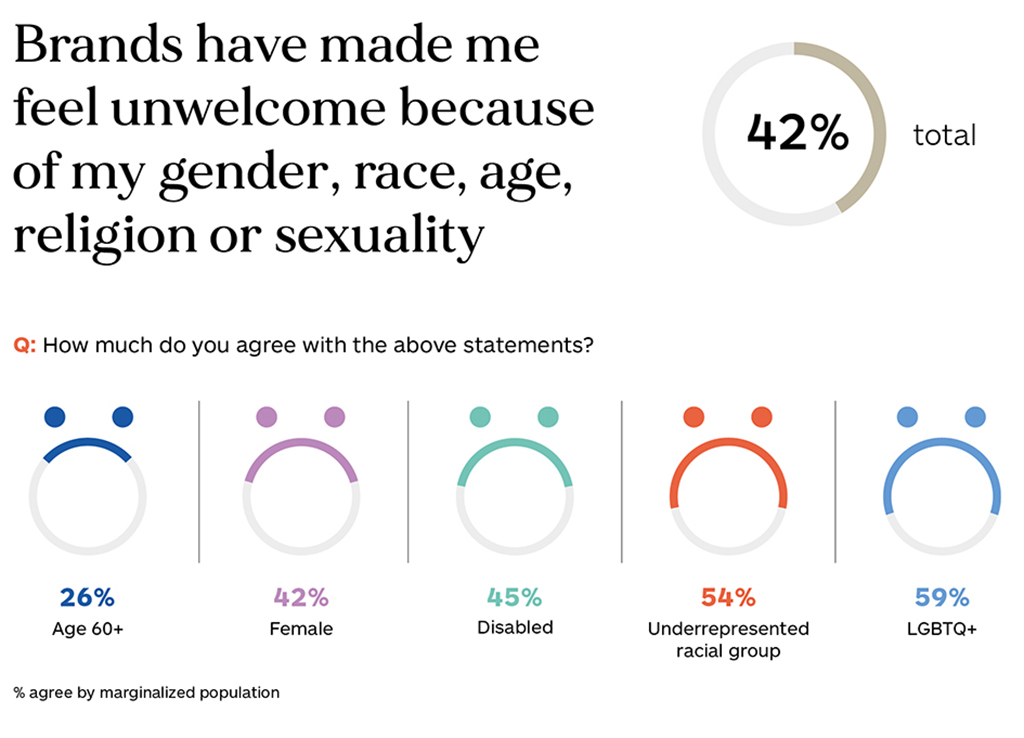

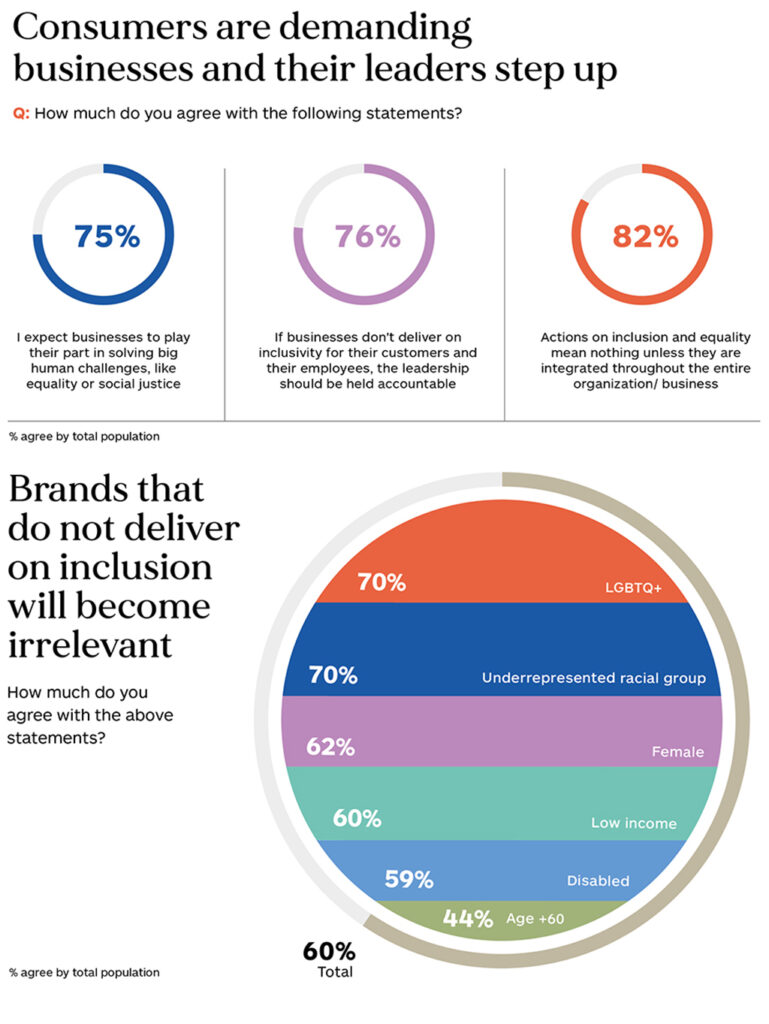

Brands that fail to commit to building a more inclusive future will become irrelevant.*

*Inclusion Next Wave. Original consumer data collected by Wunderman Thompson Data from 5,001 adults over the age of 18 in Brazil, China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The study was conducted in March and April 2022.

It all starts with identity

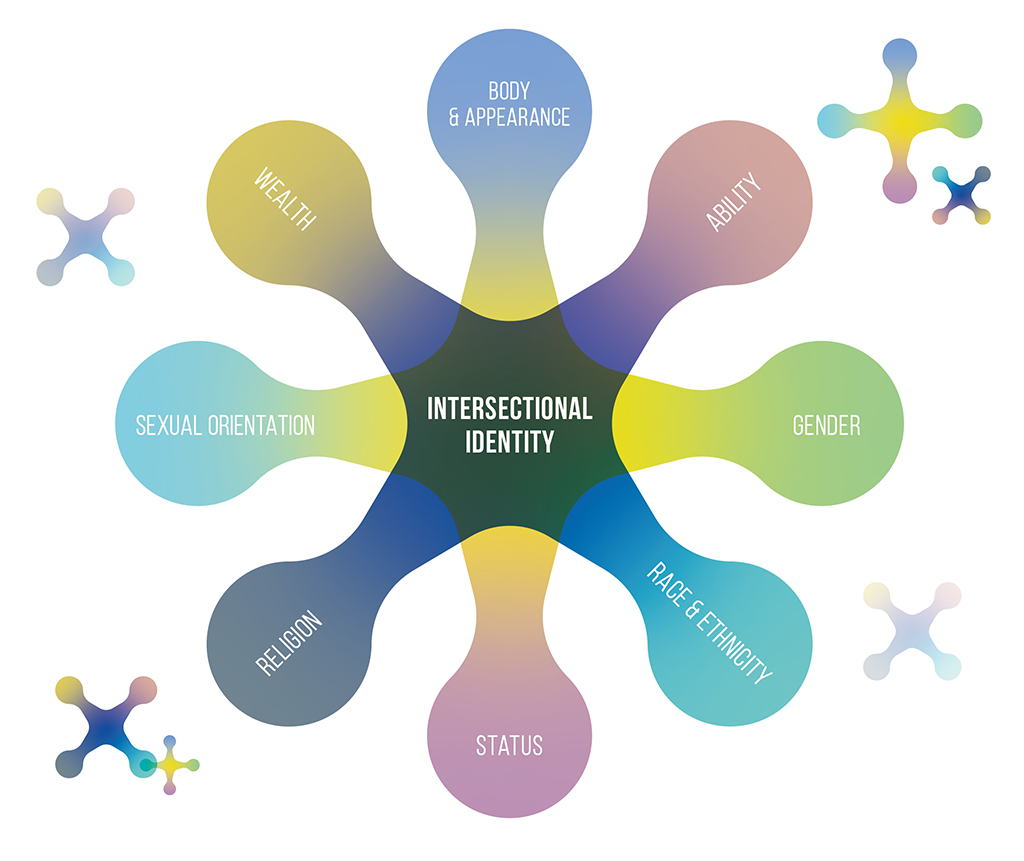

Before we talk about inclusion, we must start with identity. Identity is the system of personal characteristics and social roles by which individuals build their sense of self.

As such, identity comprises elements with which we are born and social constructs. For this reason, identity is ever-evolving and the result of factors that interact with one another, which may differ as the person moves into society.

As first introduced by theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw, the factors of discrimination and privilege that impact one’s life and that interact with identity are diverse and intersectional. These factors include race, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, education, disability, and much more.

For example, a white woman may experience forms of discrimination because of how society perceives the role of her gender; nevertheless, she will also experience the privilege of her race. The life experience of a black woman, conversely, will reflect the intersection of the discrimination suffered both as a woman and as a black person in the society she lives in.

People with permanent or temporary disabilities will also identify according to societal roles that reflect the intersectionality between their disabilities and other identitarian factors.

The organization of society around communities offers support and a key element of validation and affirmation for marginalized groups.

- People move in and out of communities depending on how they choose to identify. Gender identity can change over time, and many of the dimensions of identity that we explore are changeable. Over time, we make choices about who we are and how we want others to see us.

- Social class, gender, race, disability, and religion are all constructed categories. In time, they are reinforced by laws, institutions, and codified environments, as well as by individual actions and attitudes. In a university classroom or in a creative agency, a designer may be perceived differently because of his or her native language, nationality, age, citizenship, emigration background, family, race, or gender. – Extra Bold: A Feminist, Inclusive, Anti-racist, Nonbinary Field Guide for Graphic Designers

Why should all this matter in the context of such creative challenges?

Indeed, there will never be a definitive answer to the issue of inclusion; it must be considered a journey that accompanies the contemporary world in its continuous evolution.

Although we designers and communicators are obliged to synthesize, the risk of categorizing the ever-changing world into rigid compartments is high and is, in any case, a somewhat sterile process. Rather, it is our duty to contribute our ability to synthesize and thus help clarify the argument and clearly represent all its perspectives.

“Intersectionality is so important because people don’t realize that groups of people can be marginalized in a multitude of ways. So while we’re all very conscious about diversity, equity and inclusion, sometimes it can be narrowly focused on one dimension over the other.”

Madeline Di Nonno, President and CEO, Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media

How inclusion changes with culture

Within different cultures, exclusion can be experienced for very different reasons. And for those of us who are involved in localization, this becomes a key element to consider. So even those who create a communication campaign by asking the right questions from the outset can lose sight of the fact that in different cultures, the paradigm changes.

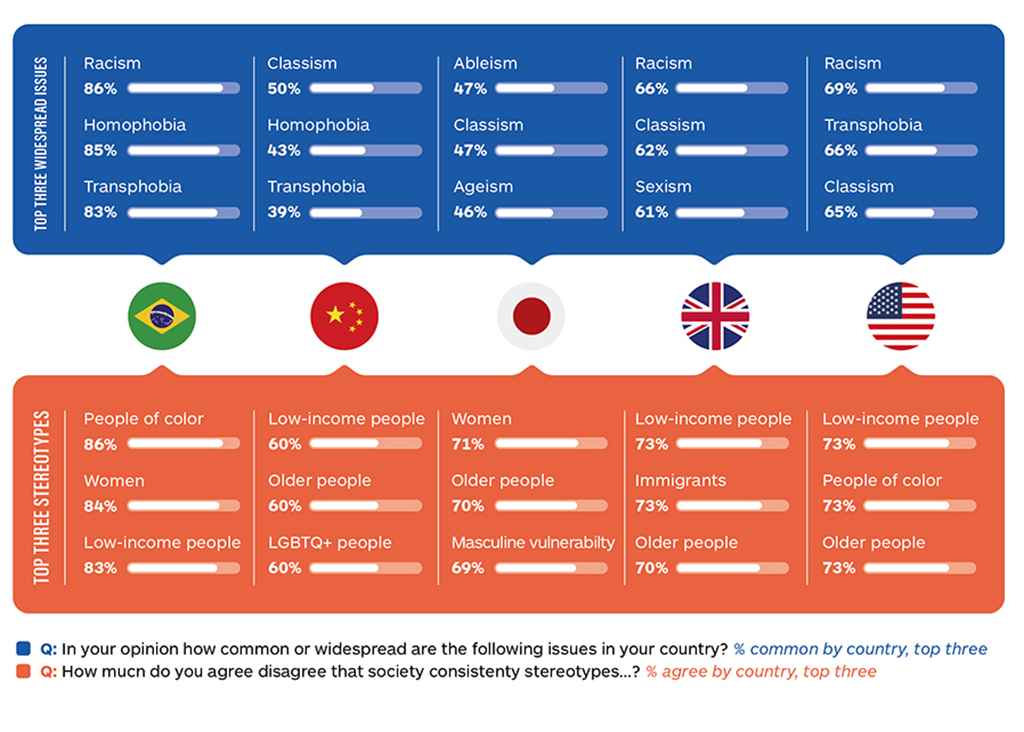

In Wundermann Thompson’s study “Inclusion’s Next Wave,” when asked the questions:

– In your opinion, how common or widespread are the following problems in your country?

– How much do you agree or disagree that society persistently creates stereotypes?

Interviewees responded in different ways. Racism is the most prevalent issue in Brazil, the UK, and the US, while class difference is ranked highest in China. Japan is an ethnically homogeneous country, but its society is based on strict gender roles that give rise to misogyny and various form of hatred against the LGBTQIA+ community. It is interesting to see how disability, class, and ageism were mentioned as the top three discrimination-related factors in this society.

Let’s focus on the question of gender. Perception of gender issues depends on culture and is partially influenced by language.

– How gender is experienced in everyday life depends on historical, social, and cultural factors. Some traits considered typically male or female have greatly changed over time, or perhaps what is normally associated with a man or woman in a given country may be unacceptable in another. Every facet of gender, be it physical aspects, social role, or personal identity, is subject to change across societies, individuals, or even within the same person over time. Culture is never static.

Sally Hines, Gender is Fluid, Nutrimenti – 2021

And those of us involved in localization must understand this and keep it in mind when trying to design a reliable model that includes this theme in the localization process as we pursue two goals:

- validation of creative work when conveying a brand’s inclusion values to diverse cultures

- in-depth exploration of the impact and extent of exclusion in various cultures to support our clients in building communication practices that relate and deliver value to the communities their brands are addressing.

Let’s see how this plays out in context. Imagine a client who is based in the United States of America and whose content and design are created in English and then localized into more than 40 languages. The content is natively inclusive in the source language, as it uses the gender-neutral form they/them. However, not all languages assigned to the localization team offer gender-neutral options. For example, standard Italian grammar does not provide a gender-neutral option, and neither does German. For such locales, text must be expanded to include masculine and feminine, or linguists will need to introduce special characters that convey the gender-neutral variant.

Longer text may exceed character limitations or degrade readability. Furthermore, special characters may not be familiar to the wider population or can cause issues with screen readers.

Since the visual organization of text and the accessibility of content vary depending on the localization choice, this calls for a command of linguistic and design expertise.

This is just one of the many examples by which localization and creativity should work hand in hand, ensuring that not only is the message conveyed by the copy accurate but also that the feel and accessibility of the content are true to its meaning for all users, regardless of their language.

The Inclusion Journey starts with the creative team

Does our team embrace different experiences, cultures, and sensitivities? As individuals, we embark on our professions with differing backgrounds and life experiences that shape our view of the world and form a framework that inspires creative ideas.

How can we build teams that include highly diverse talents? How can we embrace diverse cultural perspectives so that we systematically ask the right questions?

For many reasons, not least because professionalizing creative education is very expensive and inaccessible to most people in the West, creativity in communication and design tends to be flat and uniform. Today, most creative directors, i.e. those who apply their vision to drive new creative paradigms, are white males in their 40s.

More than 34,384 creative directors are currently employed in the United States.

Of the total, 35.3% of all creative directors are women, while 64.7% are men.

The average age of an employed creative director is 40.

The dominant ethnicity among creative directors is white (72.8%), followed by Hispanic or Latino (11.8%), Asian (7.7%), and Black or African American (4.0%). (Zippia)

Not that this necessarily denotes underlying bias or prejudice, but the introduction of broad diversity amidst a creative team would certainly boost the inclusive impact of the creative process.

Failing to do so would pose the risk of looking at the world and generating ideas from only a single perspective and not seizing the opportunity to tap into everyone’s creativity to also open up new horizons for our work.

The Dear Black Talent industry initiative by the VMLY&R Agency is one of several that seek to open doors for creative professionals from underrepresented ethnic groups. Launched globally in December 2021, the platform aims to help people of color start their careers in the industry.

The UK-based Purple Goat agency specializes in marketing to the disability community and connects brands with people with significant life experiences who can contribute to campaign relevance and authenticity.

Inclusion, communication, and representation

There is no one-size-fits-all type of creativity; the best ideas capture insights applicable to a small group of people. Universal creativity that takes into account all sensitive constituencies often leads creative ideas to veer away from real life instead of transforming it from within.

Pursuing language that hurts no one by depleting it to the core is of no use to anyone. More than anything else, it simply doesn’t work. Often in our creative work, we are asked to represent all genders, all ethnicities, and all ages in a single visual.

When this fails to convey anything, we prefer to use abstract decorative elements, thereby reducing communicative impact. So does this mean that to respond to a world that calls for more inclusiveness, creative work must necessarily become poorer, more standardized, and more neutral?

How can creative professionals generate ideas that open up new avenues for inclusive creativity? A look at how brands in communications, entertainment, and design are addressing this issue may help.

If we merely practice tokenism, i.e., treat the issue superficially by including an actor of color or a homosexual person just to be politically correct, we are neither inclusive nor credible.

Brands are trying hard to increase the number of representations of minorities, but this must be handled carefully. There is a risk of superficiality in including some and excluding others. Symbolic or stereotypical representation is harmful; it reduces aspirations and even damages what people have already achieved in life. What’s more, excluded constituencies tend to lose confidence in the brand.

Conversely, meaningful, serious, and well-constructed action on inclusion is the new obligatory path for companies and brands. They are being asked not only to use inclusive narratives but also to embrace a role in social change in the communities to which they belong, to build a truly deeply rooted inclusive world. However, storytelling has a powerful influence on culture and society, and when storytelling arises from an underlying diversity between those who create the content, those who fund the project, those who produce it, and those who represent it, it automatically generates authenticity.

Whereas communication has always followed social evolution, brands did not have the courage to represent what society had not yet thoroughly endorsed (take the case of the Gillette video about the new manliness, which led thousands of men who did not recognize themselves in that representation of “toxic masculinity” to stop using the product and break with the brand). In their role as community coordinators, brands are at the forefront of helping to build a more inclusive society today.

Towards more inclusive creativity: some examples

Many brands have chosen to value marginalized community creators, providing them with a platform that affords them high visibility. In doing so, they can support communities and promote superior representation while ensuring that they build new connections with emerging communities.

As part of the “Life Unseen” campaign, PepsiCo’s Lifewtr brand commissioned 20 artists to design the product packaging. The campaign was accompanied by a study that explored the composition of creative diversity in various fields, highlighting the problem of underrepresentation in art, fashion, music, and film. Some brands have set goals to address the problem, with Vans committing to appointing 50% of its global campaign artist and ambassador team from Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).

Mastercard’s True Name campaign, which allows people who do not identify with their assigned gender to have the name they want – what they consider to be their real name – on their credit card, is an example of how a brand can catalyze social change.

To make soccer more accessible to girls with immigrant backgrounds, in the spring of 2021, the National League of Finland, the Football Association of Finland, and Nike donated a Nike Pro sports hijab to every female player in the country who wanted one. Since the end of 2021, this has become standard practice, and every football club in the country has been able to order sports hijabs for their players from the FA free of charge.

International creative associations have started rewarding ideas that promote inclusivity. ADCE, or the Art Directors Club of Europe, brings together some 5,000 creatives from 23 European countries. Its ADCE Equal Star award honors endeavors that best promote the fight against all forms of discrimination in Europe while at the same time encouraging inclusion, gender equality, and celebrating creativity that transcends stereotypes. This year’s award went to the DiscovHery campaign by Terre des Hommes. A statue has never been dedicated to a woman in Milan. That’s why on World Women’s Day, Terre des Hommes – an NGO advocating children’s rights – presented the first child-height campaign, which, playing with perspective, replaced Milan’s male statues with those of women capable of inspiring new generations. The posters supported a petition addressed to citizens to build the first female statues aimed at inspiring future generations. The first statue was inaugurated a few months later.

Gaming and the world of entertainment

The entertainment industry has a great influence on young people and how they view the world. This industry, in particular its video game segment, has been propagating gender stereotypes and the over-sexualization of women for decades. The NGO Women in Games, which advocates for greater gender diversity in the video game industry through its #GenderSwap campaign, aims to challenge stereotypes and pave the way for a new gender representation.

At the same time, efforts are underway in the world of cinema to engage hitherto marginalized communities. Marvel’s Black Panther, released in 2018 with a 90% black cast, is among the highest-grossing superhero films ever (with a global box office of $1.3 billion).

The series Ms. Marvel debuted in June with the first Muslim superheroine, played by Iman Vellani. For many community members, seeing a young Muslim superhero on television breaks a long-standing and outdated pattern of negative representation.

Makkari, the first deaf superheroine played by Lauren Ridloff, debuted in Eternals in 2021, bringing disability to the forefront.

Disney’s Encanto featured an entire Latino/Hispanic cast and was widely celebrated for showing a non-stereotypical view of Colombian culture. Many of the actors are of Colombian descent, and the directors have diverse Latino backgrounds.

Channel 4 has chosen an all-disabled team of presenters to cover the Beijing Paralympics. Zaid Al-Qassab, Chief Marketing Officer and Director for Inclusion and Diversity at Channel 4, said:“The presence of disabled presenters and personalities helps audiences move away from stereotypes and oversimplifications to think more about the range and nuances of disability.”

Toward inclusive design

Referring to design as a fundamental principle, we can say that inclusive design is simply good design. That said, nothing we produce will work for everyone. Design in itself can never generate solutions that work for everyone, even by finding the lowest common denominator: wanting to please everyone does not work for anyone. Design can imagine different ways of using an object so that everyone feels like part of the experience.

In Mismatch, Kat Holmes writes that precisely engaging in design for diversity is the key to our collective future. She argues that if there is a method we can share to this end, it consists of three steps:

1 – Recognizing exclusion. Exclusion occurs when we solve problems using our own biases.

2 – Learning from human diversity. Human beings are the true experts in adapting to diversity.

3 – Solving a problem for one person and extending it to many. Focusing on what is truly important to human beings.

“Designing for human diversity might be the key to our collective future. It’s going to take a great diversity of talent, working together, to address the challenges we face in the 21st century: climate change, urbanization, mass migration, increased longevity, and aging populations, early childhood development, social isolation, education, and caring for the most vulnerable among us in an ever-widening gap of economic disparity. You never know where, or who, a great solution will come from. Already there are inclusive solutions quietly at work in our world. They are the early examples by which to measure inclusive outcomes.”

Kat Holmes, Mismatch. How Inclusion Shapes Design, The MIT Press, September 1, 2020

The design studio Frog addresses the issue of inclusion through The Universal score, an inclusive assessment tool that asks a series of new questions to help designers evaluate their ideas based on more inclusive criteria.

Questions such as:

Does this idea promote mental well-being?

Does this idea encourage belonging?

Does this idea respond to physical needs?

Does the idea take cognitive differences into account?

By asking these questions early in the process, we can begin to talk about how inclusive one idea is as opposed to another.

Once again, the creative supply chain theme emerges: only by asking the right questions at the beginning can we begin the creative journey toward inclusion.

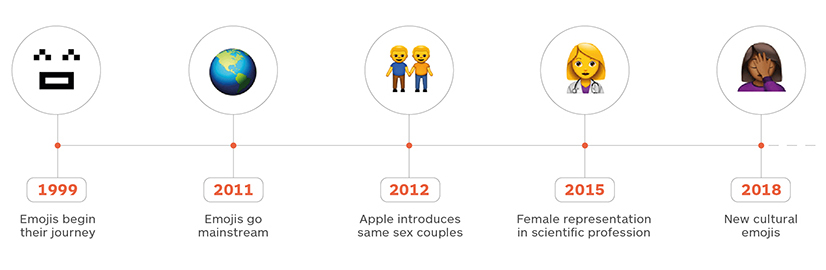

Recalling the principle of representation in design, consider Emojis:

In 2011, Apple launched its first emoji library. It was rightly criticized for its lack of diversity. In 2012, it introduced emojis for same-sex couples; in 2015, options for skin color for other ethnicities and female representation in scientific professions were added. As for persons with disabilities – they had to wait for eight more years. Cultural emojis remained strongly Westernized until 2018. And a gender-neutral emoji was not available until 2019. This resulted in a sense of exclusion for millions of people.

A very interesting design trend today is the emergence of Inclusivepreneurs, entrepreneurs from disability communities who are innovating for themselves by designing products and services that address the unmet needs of their communities. The pandemic and new levels of access to technology are giving rise not only to new representations but to real innovation.

Localization is part of the user experience and representation discourse. If the ideas promoted in the original concept cannot be safely transposed to other cultures, then that content risks becoming exclusionary. It is very important for brands to share creative decisions with the people responsible for localization and to consider their feedbacks regarding the meaning of key concepts in different cultures. This is particularly relevant in a society of digital nomads and increased personalization of user experience.

What does the future hold for increasingly inclusive brand localization?

Considering everything that we have examined, we have begun to answer some of our questions. To be increasingly inclusive, the key points that we can translate into action are:

- Discuss Inclusivity from day one

We must bring the inclusion theme to the forefront of the creative process. The creative translation team can support brands on this issue early in the creative process through discussion with the marketing and localization team at the time of creative idea generation.

- Ask the right questions

Devising the right questions to ask at the time of idea generation is critical for activating a cultural validation process on inclusivity that is robust and credible. Imminent, Translated’s research center, can provide support in defining the questions, and the Community Intelligence Network can help research what the theme means for each culture.

- Improve Cultural validation and co-creation

Applications can then be validated across cultures through a cultural validation and co-creation process, using cultural co-creation spaces centered on a unique theme that leads each culture to express its creative potential on a defined topic. This is something that the Translated community of Inclusive local culture specialists can provide as a service. The Translated community of linguists can support brands in laying the groundwork for a concept.

- Bring diversities to life

Draw on the diversity of cultures to bring new stories to the world, giving visibility to hitherto ignored cultures. In this sense, the Translated community of linguists can support brands in gathering creative material from various language cultures.

- Submit design for validation through diverse cultures and communities

Verify, through an extensive survey of the linguist community, the degree of inclusiveness of the design. We already provide a cultural validation service for various linguistic cultures that we can integrate with other communities.

What we are instead thinking of doing:

- We are working to define an Inclusive score for brand localization. On the basis of evaluation criteria, it will help us measure the inclusive potential of brand campaigns.

- Together with our community of linguists, we are starting to run workshops to create a shared inclusion-themed glossary. This glossary will continuously evolve in line with the evolution of language itself and contemporary society.

- We have begun to create an inclusive brand guideline model to support our clients in localization projects.

The decision-making process should include all actors involved in the localization process. Linguists and Language-specific Inclusivity Experts (LsIEs) provide cultural insights. The responsibility for flagging derogatory language, however, cannot be entirely borne by them. For this reason, Language Service Providers (LSPs) have a responsibility to acquire talent and provide them with training and support, creating a safe space where everyone feels supported by the community in speaking their voice. Clients are part of this conversation, as they need to be involved, ultimately by providing key information about the target audience and design concepts envisioned for the native content.

Here are some of the key language inequities and linguistic microagressions that should be considered when creating inclusive localization:

- Sexist language: this is language that confirms harmful gender stereotypes and includes the biased use of specific genders for certain professions. A typical example is how doctors are usually perceived, and translated, as males and nurses as females. Sexism is so embedded in our language that artificial intelligence (AI) has absorbed it. This is a threat to localization because when gender-specific context is not conveyed, people tend to revert to their subconscious bias. This is why context and visuals are always required to support the language team in making informed decisions.

- Trans-exclusionary and Homophobic language: this form of language discrimination includes microagressions related to people’s gender identity and sexual orientation. We have previously addressed the question of gender-neutral pronouns used by the intersex, non-binary, gender non-conforming, and trans* community in striving to break the confines of masculine/feminine binarism. Other examples include stereotypes about the heterosexual family and the pathologization of lived experiences. LGBTQIA+ national associations undertake intense work on language, keeping glossaries up-to-date and available to the wider public.

- Ableist language: Ableism is deeply connected to design and accessibility, but microaggressions, too, are part of our language. Forms of microaggression include the medicalization or the infantilization of lived experience. Also in this case, we must heed the voice of local disabled persons communities in order to foster the use of language that is coherent and relevant to how people affirm and define themselves in different cultures.

- Racist language: The racial lexicon differs according to country and when localizing, and we should be aware of country-specific issues: racialized minorities may exist only in certain countries. When localizing content that refers to racialized minorities, clients, LSPs, and LsIEs should engage with each other to ensure that relevant minorities are included in the scope of the project.

- Aporophobic language: This is language that diminishes people based on their socioeconomic status. This includes poverty but also key factors related to class, caste, and education. An example of harmful language is one that uses elevated jargon, inaccessible to people without college degrees. This frequently occurs when localizing legal and medical text, even when the latter are thought to be user-facing. LSPs have a key role in advocating for plain language, persuading clients, and guiding linguists in their work.

Other forms of linguistic inequities include discrimination based on religion, cultural appropriation, ableism towards neurodivergent people, and ageism.

Localization teams and clients should work together when addressing an inclusivity or accessibility issue, but certain general guidelines should also apply.

Foremost among gender-neutrality approaches, there are two key elements that creative localization teams should consider.

One is to choose between identity-first or person-first language. A case in point is the choice between disabled people and people with disabilities. In everyday life, it is good practice to use whichever form our interlocutor uses to define themselves. But what to do when you have to make the choice for everybody else? With copywriters making source content choices, creative localization specialists should be part of the collective effort, helping to make informed decisions based on their cultural standards and the expert opinion of national associations and groups.

Another key decision is whether to adopt active or passive language. This is evident when juxtaposing the term homeless with unhoused. While the former implies the deficiency of a person experiencing homelessness, the latter term stresses the concept of societal failure and is more specific, as it describes a specific type of homelessness. When we make select a linguistic option in English, however, we should share its intention with all local teams, pursuing consensus not just on the reasons but also elements that support our choice. If well documented, LsIEs can thus transfer a vision into their culture, undertaking the necessary effort with local associations to find a suitable translation.

We have mentioned how solutions available in a given language may be unavailable in another. What’s more, the choice to solve one linguistic inequity may cause another inequity in a specific culture. Take the example of the special characters used in certain languages, like Italian, to create gender-neutral forms that risk making content inaccessible to people using accessibility tools and screen readers.

This calls for an important reflection. There is no such thing as one inclusive language. We are heading toward a society where even within the same language, communities use codified lexicons that can be very specific. A relevant example could be the tiresome endless acronyms used in business language, which are absolute gibberish to people who don’t work in particular sectors. According to the inclusive practice we have learned, the best approach is to always explain your acronyms when you use them outside your inner group.

This is how we should treat inclusive localization: we should open language to everyone, everywhere, and in every possible way.

In the journey to a more inclusive future, collective creative intelligence is what will definitively support change. As creative professionals, designers, communicators, and localization experts, we can contribute in important ways in every phase of our work – from when we think, create, and produce, to when we narrate the world. Inclusion does not mean impoverishing language or making creativity as neutral as possible; rather, it calls for opening up multiple new avenues for creativity, drawing on the diversity and uniqueness of people and cultures to give them visibility and present their stories, needs, and perspectives to the world.

Working with more than 300,000 translators, we have the opportunity to access an infinite pool of ideas and the chance to look at the world and its multiculturalism from a unique and privileged perspective.

This journey might be perilous, but if we apply our collective creative intelligence, we will probably succeed in fostering fruitful exchange on this topic and generating ideas that will have a positive impact on our society.

Ideas for visuals and quotes related to linguistics

Schwa is the character used in Italian to overcome gender binarism. Schwa was described by Italian sociolinguist Vera Gheno as the best option for gender-inclusive language. Albeit not available in the Italian script, the character has a sound already familiar to Italian speakers and thus easily adapts to screen readers. It is used as a final vowel, at times requiring a truncation of the word. Initially used in transfeminist circles, it has become widely used and, since 2021, has become available in both Android and Apple keyboards.

gendersternchen and doppelpunkt are the two characters used in German to overcome the universalization of the masculine form. The two characters are used to create a conjucture between the masculine and the feminine ending and sound like a small pause between the two. Screen readers are evolving to adjust to the elision, and so are television and radio journalists, contributing to a broader use of the form.

Photo credit: Max Bender, Unsplash