Global Perspectives

June 2024

Key Statistics

- The 4th biggest economy in Asia.

- The 11th biggest economy in the world.

- The 7th country in the world according to the Human Development Index (UN, 2008).

- Ranked 1st in industrial robot density worldwide (1000 robots per 10,000 employees).

- Ranked 3rd in the world for per capita spending on skincare (after the USA and Japan).

“Hanawon” (하나원): where the two Koreas meet

In Anseong, an industrial city 90 km from Seoul, there is a center – Hanawon – where North Korean escapees spend their first three months in the South, learning to adapt to a capitalist democracy and integrate into South Korean society. After three months, they leave with a new identity card, South Korean citizenship, and many uncertainties about their future.

Hanawon, a facility opened in 1999 during the Sunshine Policy era of détente between Seoul and Pyongyang, accommodates only women and children, while men are hosted in a separate center opened in 2012. Before arriving at Hanawon, defectors have already undergone intelligence scrutiny to ensure they are not spies sent by Pyongyang. After three months, they leave with a new identity card, South Korean citizenship, and many uncertainties about their future. Hanawon’s primary objective is to “re-educate” North Korean defectors for integration into South Korean democracy. It also provides medical and psychological support, vocational training, and practical skills such as opening a bank account, renting an apartment, and using public transportation. Hanawon is where the two Koreas converge, highlighting their differences and reflecting the evolving relationship between the two nations.

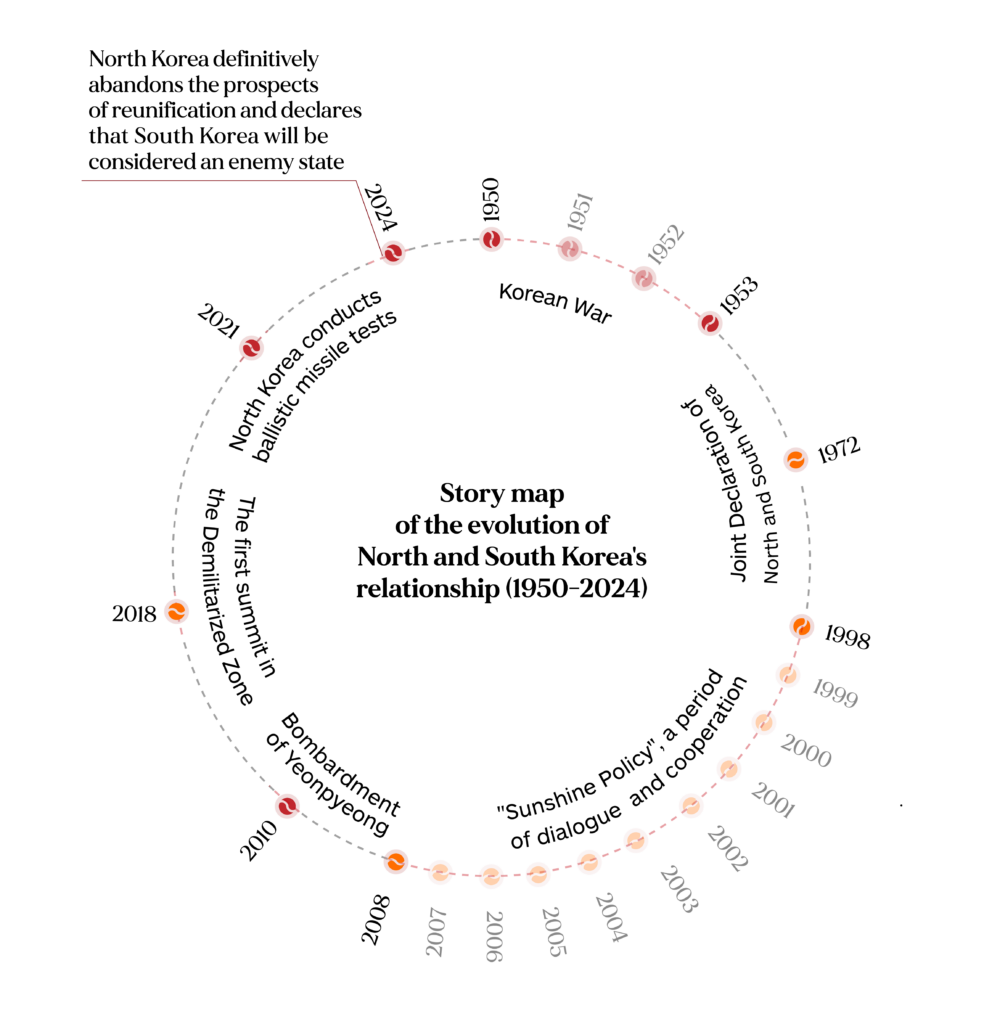

Through the decades, historical incidents have served as markers of escalating tensions. From the chilling 1968 assassination attempt on Park Chung-Hee to the tragic 2010 sinking of the Cheonan and the subsequent shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, each event has contributed to the ebb and flow of the peninsula’s delicate balance. Hope flickered with moments of dialogue, such as the 1972 reunification talks, only to dim as tensions flared anew with North Korea’s nuclear pursuits. The leadership transition in 2011, as Kim Jong-Un assumed power, heralded a period of heightened nuclear activity, culminating in the dramatic 2013 nuclear test.

Source: Wikipedia

Moon Jae-In’s ascent to the South Korean presidency in 2017 initially promised a different approach, emphasizing engagement over confrontation. Yet as tensions mounted, Moon’s stance shifted, aligning with the U.S. in response to North Korean provocation. However, amid the geopolitical posturing, the 2018 Winter Olympics emerged as an unexpected crucible for reconciliation. The historic summit of 2018 unfolded against the backdrop of global sportsmanship, echoing promises of denuclearization and fostering cautious optimism. Yet as the hopes kindled by the Pyeongchang summit flickered, the abrupt collapse of the 2019 Hanoi summit served as a stark reminder of the fragility of diplomatic endeavors. Renewed discussions ensued in South Korea, contemplating joint ventures as a means of thawing inter-Korean relations.Amid these diplomatic maneuvers, a seismic shift occurred in 2024 as Kim Jong-Un renounced North Korea’s long-standing pursuit of reunification with South Korea. This paradigm shift, marked by Kim’s labeling of South Korea as the “principal enemy,” reverberated through North Korea’s media and monuments, reshaping perceptions and potentially paving the way for future conflict.

Economically, the unstable interactions between the two Koreas not only affect the two nations but also have substantial implications across Southeast Asia. Geopolitical fluctuations impact the GDP of both countries, with South Korea’s strategic position being particularly significant in the context of China-U.S. relations. Historically, South Korea has maintained strong ties with China, reaffirmed in 2023 with China’s status as South Korea’s main export partner. However, persistent tensions with North Korea have strained this relationship. Consequently, South Korea has been strengthening its ties with the United States, particularly in sectors such as computer chips and robotics.

South Korea's GDP growth rate compared to North Korea 1990-2022

Source: Statista

South Korea finds itself in a contradictory position, acting as a crossroads between East and West. These dynamics heavily influence the opinions of the South Korean population regarding inter-Korean relations. While the majority (approximately 83.3%) are not interested in reunification and are content with the current situation, around 37% of citizens believe that collaboration between the two countries is necessary (Statista, 2023).

“Chaebols” (재벌): the Miracle on the Han River

재벌이 재채기하면 한국 경제는 감기에 걸린다,

“When the chaebols sneeze, the South Korean economy catches a cold.”

This South Korean saying encapsulates the pivotal role of chaebols, colossal conglomerates, in shaping the nation’s economic trajectory.

After the Korean War, South Koreans faced the need to rebuild their country from the ground up. In the early 1960s, the military government led by the strongman Park Chung-Hee favored the growth of large industrial and financial conglomerates, modeled after the Japanese zaibatsu, and organized based on principles of loyalty and ideological integrity.

Zaibatsus are Japanese business groups that came into being prior to the First World War. After the Second World War, zaibatsus evolved into keiretsus, associations of firms whose CEOs would regularly hold collaborative meetings. The keiretsu system consists of bank-dominated industrial groups in which the bank center functions as a capital provider and through which a monitoring function is established. Chaebols share many characteristics with keiretsus, including networks of affiliated firms known as kyeyols (the Korean pronunciation of keiretsu). However, the chaebol lacks a corresponding external monitoring function: the kyeyol firms are placed under the direct control of the group’s central planning office, which is in turn controlled by the group’s founding family members.

In the Korean regulatory environment, chaebols have pursued an alternative to the keiretsu’s bank-centered financing system by devising internal market transactions. Structurally, chaebols are also more family-held, hierarchical and centralized, and they rely more heavily on government relations than their Japanese counterparts. There is a reason for these differences. Korean chaebols were deliberately created to become champions of a fast-growing economy, while the zaibatsus grew in response to the need for procurement of military supplies following Japanese expansion in the 1930s. Also, in terms of family ownership, blood relations are of the utmost importance in Korean society.

In fact, the term “chaebol” derives from the combination of the characters for “wealth” and “clan,” and it is to the owning family that individual members of the conglomerate must show their loyalty, a concept considered fundamental in Korean society. Their ascendancy can be attributed to a confluence of factors: favorable government policies, access to abundant state resources, and a penchant for diversification across pivotal sectors.

Source: Daxue Consulting

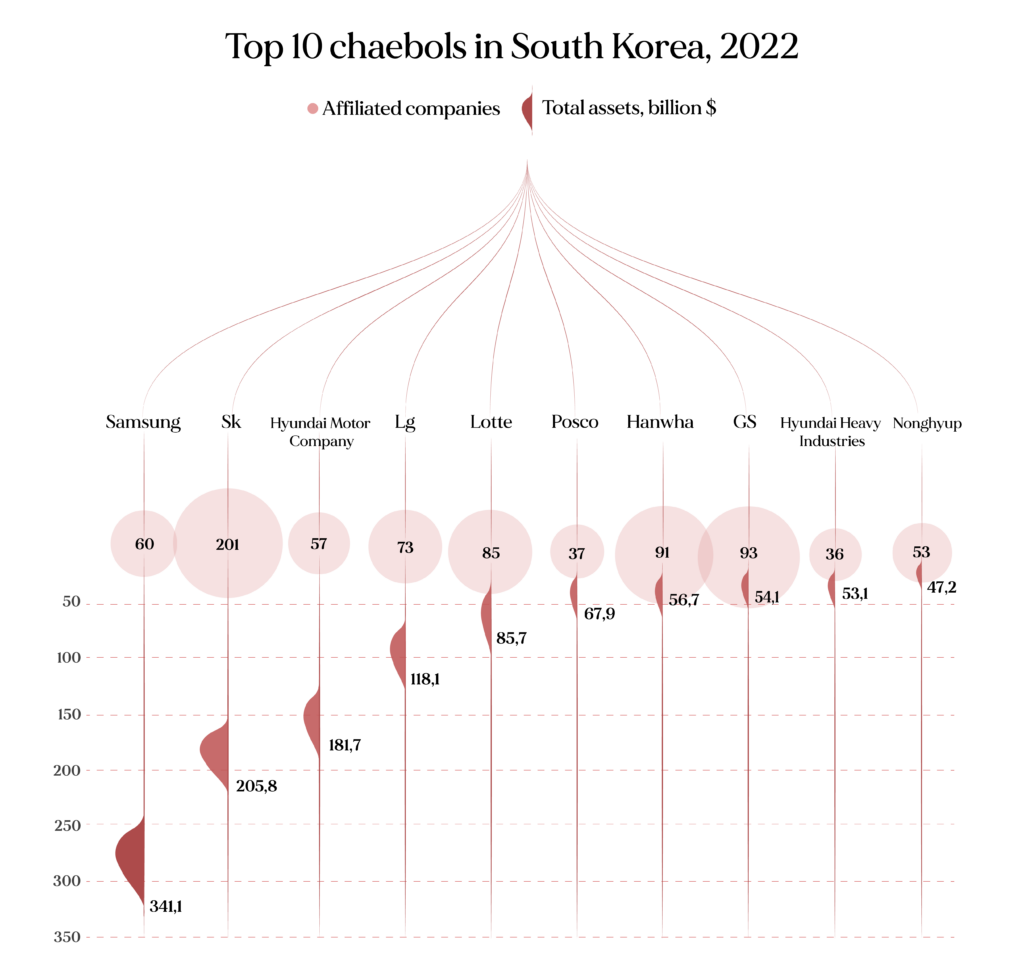

While there is no consensus, most scholars agree that a chaebol is defined by three structural business traits: a chaebol consists of many affiliated firms operating in a number of diverse industries; ownership and control of the group lie with a dominant family; and the business group accounts for a large percentage of the national economy. Initially focused on heavy industry, these groups gradually expanded into other key sectors of the South Korean economy, such as shipbuilding and finance.

The discussion surrounding chaebol reform was prominent in the early 21st century with regard to South Korea’s political and economic trajectory. Electoral campaigns often highlighted promises of change, including legislation aimed at combating corruption and restructuring the conglomerates. Various measures were implemented, leading to a somewhat stricter legal environment that resulted in several notable convictions, such as that of Chey Tae-Won, chairman and CEO of SK Group, in 2003, and the resignation of Samsung chairman Lee Kun-Hee in 2008 following allegations of tax evasion. Laws enacted in 2004 imposed limits on chaebols’ investments in affiliated companies, mandated the disclosure of shares held by family members of top executives, and granted the Bank of Korea authority to investigate the assets of company owners’ relatives. However, critics contended that reform efforts were sluggish, tentative, and incomplete, hindered by the enduring influence of the chaebols and concerns about significant job losses resulting from the closure of unprofitable enterprises.

The five main chaebols alone make up about half of the South Korean stock market; Samsung’s revenues correspond to about a fifth of the national economy, yet only 17% of the population is employed by chaebols. The chaebol’s towering influence – 77% of South Korea’s economy is controlled by them – has yielded a landscape marked by pronounced economic disparities. Wealth inequality is very high: the share of total wealth held by the bottom 50%, middle 40%, and top 10% is equal to 6%, 36%, and 59% respectively. Inequality levels have increased in the last 30 years, with the middle class and working classes recording a slight decline in their share of total wealth, to the benefit of the top 10%. In 2021, the wealthiest 10% of the population owned 58% of the total household wealth (World Inequality Report, 2022).

Source: USC Economics Review

Yet the South Korean narrative is not solely defined by chaebol hegemony. Its transformation from a primarily agrarian economy to a technological juggernaut, aptly termed the Miracle on the Han River, is emblematic of its resilience and ingenuity. When Korea joined the OECD in 1996, it had already experienced over three decades of remarkable growth. This growth was fueled by an export-oriented economy supported by a diligent and increasingly well-educated workforce, along with high rates of saving and investment.

The term “chaebol” derives from the combination of the characters for “wealth” and “clan”, and it is to the owning family that individual members of the conglomerate must show their loyalty, a concept considered fundamental in Korean society.

The transformative “Miracle on the Han River” turned Korea from one of the poorest nations after the Korean War into an economy with a GDP per capita comparable to that of some European countries. However, it still lagged about 30% behind the OECD average in 1996. Over the last 25 years, Korea has undergone significant economic reforms, aligning its policies with OECD best practices across various sectors. It has also integrated more closely with the global economy and further developed its technological and human resources, leading to its GDP per capita converging toward the OECD average. Strategic investments in research and development, coupled with a skilled workforce and robust government-industry collaboration, have propelled South Korea to the vanguard of technological innovation. Key partners like China, the U.S., and Japan drive demand for South Korean goods, particularly semiconductors and robotics.

“Tal-Jo”(탈조): Escape Hell

A catchphrase has taken hold among young Koreans in recent years to describe their country: “Hell Joseon,” with “Joseon” being the name of a long-dead Korean kingdom. That phrase is now being superseded by a new term, “Tal-Jo” – a portmanteau combining “leave” and “Joseon” which, conversationally, might best be translated as “Escape Hell.”

Young South Koreans between the ages of 19 and 34 feel more anxious about life than the older generation: 8 out of 10 South Koreans aged 19 to 34 viewed South Korea as “a hell,” while 7.5 out of 10 said they hoped to leave (Hankyoreh, 2019). There are many social reasons underpinning this attitude, such as the lack of social mobility, the demographic crisis, and the extremely high population density.

금수저 vs 흙수저 – The “spoon theory” is a popular concept in South Korea that symbolizes social mobility. It refers to the idea that individuals are born with either a “golden spoon” or a “dirt spoon,” representing their socioeconomic background and opportunities in life. The “spoon theory” underscores the entrenched social stratification in South Korean society and highlights the barriers faced by individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds in achieving upward mobility.

According to a 2018 OECD report, a Korean child born into a family in the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution would need an estimated five generations to earn the average income.

“Tal-Jo” – a portmanteau combining “leave” and “Joseon” which, conversationally, might best be translated as “Escape Hell.”

After experiencing four decades of annual growth at a remarkable rate of 6–9 percent, South Korea’s economic expansion has slowed to 2–3 percent or less annually since 2012. While slower growth is typical in advanced economies, South Korea faces structural vulnerabilities contributing to this deceleration. Firstly, the nation’s heavy dependence on exports, particularly in industries such as electronics, automobiles, and shipbuilding, exposes it to external economic fluctuations. Global economic downturns, trade tensions among major economies, and disruptions in global supply chains have all diminished demand for South Korean goods and services, thereby impacting GDP growth. Moreover, structural challenges such as high household debt, labor market rigidity, and an overreliance on chaebols impede innovation and entrepreneurship, hampering long-term economic prospects. The low growth rates also underscore South Korea’s demographic challenges, with viable solutions limited unless there is a significant change in birth rates.

A whole generation in their 20s and 30s has been humorously labeled the “Sampo” or “three giving-up” generation for relinquishing courtship, marriage, and parenthood due to financial constraints. Now dubbed the “N-po” generation, they lament the unattainability of various life milestones, from securing meaningful employment to home ownership. South Korea is now grappling with the lowest fertility rate in the world, exacerbating the demographic crisis characterized by an aging population and declining birth rates.

This trend is attributed to multiple factors, including expanded educational and career opportunities, costly childcare expenses, inadequate government assistance in achieving work-life balance, societal pressures concerning social status and gender norms, and the challenges associated with urbanization and high living costs, particularly in urban centers like Seoul. In 2023, the country recorded its lowest number of births since 1981, with around 230,000 births (compared to over a million in the 1970s), less than half the figure seen in 2000. These demographic shifts have profound implications for workforce participation, consumer spending, and social welfare expenditure.

Number of births in South Korea from 1981 to 2023

Source: Statista

In stark contrast to the optimism and hope prevalent in previous generations, data from the World Values Survey indicates a decline in Koreans’ belief that they have “freedom of choice and control over their lives” since 1990. Paradoxically, despite South Korea’s globally acclaimed filmmakers and artists, significant segments of society are depicted as grappling with a crisis of hopelessness. This “Paradox on the Han River” defies simple explanation. The future of the nation hinges on its response to this existential challenge—whether it paves a path toward shared prosperity for the next generation or tragically fails to address its social divisions.

South Korea

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!“Hallyu”(한류): K-Culture conquers the world

Hallyu, often referred to as the “Korean Wave,” encapsulates the global spread of Korean culture, spanning music, television, film, fashion, and more. Originating in the late 1990s, hallyu surged in popularity, captivating audiences worldwide with its dramas, infectious K-pop tunes, and innovative entertainment industry.

The economic ramifications of hallyu reach beyond its cultural resonance, profoundly impacting South Korea’s economy. The export of Korean entertainment content, notably television dramas and K-pop music, is a formidable driver of economic expansion, injecting billions of dollars annually into the country’s GDP, with +35% growth between 2018 and 2022.

In 2021, the industry generated KRW 137.5 trillion in sales (up 7.2% year-on-year), exported USD 12.45 billion (up 4.4% year-on-year), and had approximately 108,000 businesses (up 9.1% year-on-year), recording average annual growth rates of 5.0% for sales, 10.0% for exports, and 0.7% for the number of businesses (InvestKorea, 2022).

This surge in cultural exports has not only propelled South Korea onto the global stage but has also catalyzed growth in ancillary industries like tourism, fashion, beauty, and gastronomy. From the television survival drama Squid Game to the chart-topping girl group Blackpink, Korean popular culture is breaking new ground and garnering international recognition. Its global cultural influence has spread to India, a nation of 1.4 billion people (compared to Korea’s 50 million), where Korean is the fastest-growing language and is taught in secondary schools.

Source: Invest Korea

The gaming industry in Korea is poised to continue prospering in 2024, cementing South Korea’s status as a global gaming powerhouse. Ranked as the 4th largest video game market globally, South Korea is renowned as the epicenter of Esports – a phenomenon that drives many Korean youths to pursue professional gaming careers. From PC bangs to home setups, gaming is ubiquitous across all age groups in Korea. The rapid expansion of IT infrastructure has paralleled the gaming market’s growth, leading to the widespread availability of internet cafes and PC rooms nationwide. With the mobile gaming market alone surpassing $7 billion and over half of the population gaming on smartphones, Korea’s gaming culture has thrived, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. PC bangs, popular among students seeking stress relief, can be found on every corner at affordable prices. Many Korean gamers devote as much dedication to gaming as they do to their studies, reflecting the country’s immense gaming community. Consequently, it’s no surprise that some of the world’s top gamers emerge from Korea.

Size of the gaming market in South Korea from 2006 to 2022

(in trillion South Korean won)

Source: Statista

These cultural phenomena have transcended borders, winning over fans in Asia and beyond, fostering a global community of enthusiasts united by their love for Korean culture, language, and traditions. In an international survey about these products, when respondents were asked what first comes to mind when thinking of Korea, 17.2% mentioned K-pop, 13.2% mentioned food, 7% mentioned K-dramas, 6.3% mentioned ICT products and brands, and 5.2% mentioned beauty products. Additionally, 68.8% of respondents had a positive opinion of this content. A favorable attitude toward hallyu was highest in Indonesia at 86.3%, followed by India at 84.5%, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) at 83% each, and Vietnam at 82.9%.