Localization

Multilingualism within companies brings about many benefits, but can it bring problems too? Airbnb’s Head of Localization Salvatore Giammarresi puts the spotlight on the importance of developing a company’s lingua franca.

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart.”

Nelson Mandela

The evolving language landscape within a company

A“lingua franca”, is a language or mixture of languages used as a medium of communication by people whose native languages are different. In most companies it’s the language and culture shared with everyone inside the company that allows team members to communicate among each other, collaborate, and get things done.

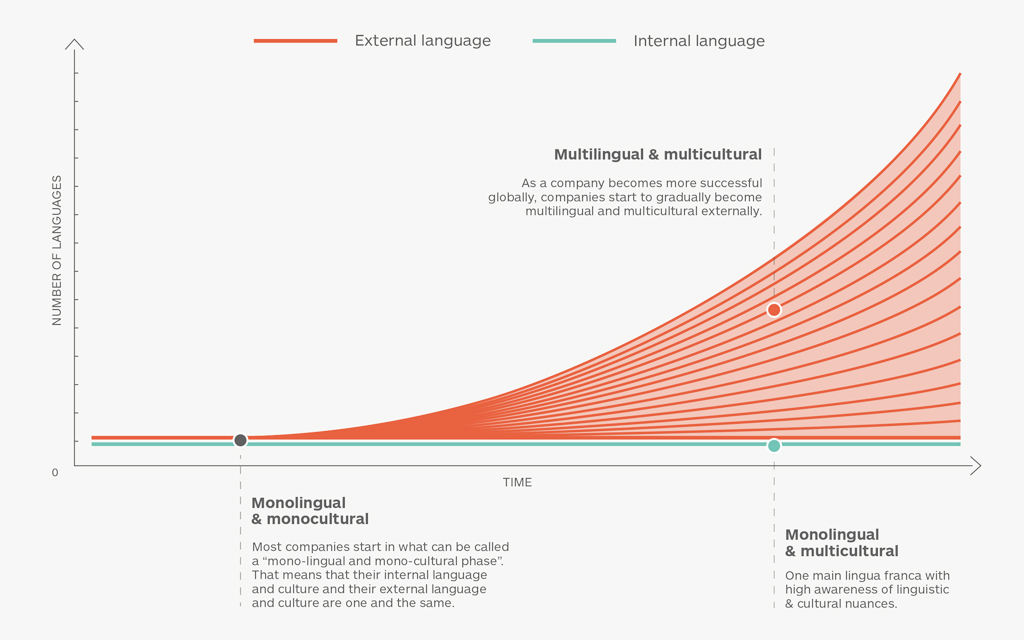

Most companies start in what can be called a “monolingual and monocultural phase”. That means that their internal language and culture and their external language and culture are one and the same. This is common among companies founded in one country, hiring native speakers from that country and offering products and customer support only in the language of that country.

The internal language and culture of a company is what is used daily internally, by founders, the board and employees. It’s the lingua franca of the company.

The external language and culture is what is used and supported for the company’s website, products, marketing, services and customer support. It mostly matches the language and culture of the primary users of the company’s products.

As a company becomes more successful globally and their products gain increasing traction in other countries, a company realizes it needs to start investing in localization in order to better reach their growing multilingual and multicultural users, and further enable and drive global business.

Usually around this time a company starts to hire multilingual and multicultural employees, both at their headquarters and in emerging satellite offices.

At this point companies continue to be monolingual and monocultural internally, but they start to gradually become multilingual and multicultural externally and in their local offices, where employees speak both the local language and the lingua franca of their headquarters.

There is a continuum in which companies still rely on a lingua franca but cater more to the nuances of local language and culture. Over time, at their own pace, they go from a monolingual and monocultural phase (“mono”) to a multilingual and multicultural one (“multi”).

During this evolution, companies should become aware of when and how their internal language and culture is supporting or hurting their external languages and cultures.

The first and largest quantitative study on lingua franca across a variety of corporations globally, conducted in 2013 (by A.W. Harzing and M. Pudelko), sheds some light on how companies deal with lingua franca. Interestingly the data varies considerably based on the location of the headquarters. For example 23% of all companies studied, stated that they don’t have a lingua franca, either confirming the low awareness and/or priority of using a common language. However, within this group, 47% of companies are based in Asia, 23% are based in Anglophone countries, 17% are based in continental Europe and 12% are based in Nordic countries.

Across all the companies that adopt a lingua franca, 48% adopt the language used in their headquarters, and 52% pick a different language. 70% of companies based in Asia use the headquarter’s language and only 30% use another language. While 100% of companies based in Anglophone countries use the headquarter’s language (English) and 100% of companies based in the Nordic European region use another language.

All companies that were studied that use a language other than the headquarter’s language, use English as their lingua franca. This confirms the current special status of English as a global lingua franca for business.

Linguistic, cultural and dual “expats”

All languages and cultures come with their own status markers, rituals, gestures, social power dynamics, beliefs, norms, and more, alongside conscious and subconscious biases.

During the first “mono” phase, all of these factors heavily influence the voice, tone, metaphors, idioms, cultural references and imagery of the internal and external language of the company. In this early phase, the focus on one language and culture is highly beneficial, as a common shared perspective permeates and strengthens all internal and external comms, products, marketing and programs. The strong presence and use of the same language helps build consensus, align people and teams, streamline decision making. It acts as a multiplier, a unifier and a cohesive strategic alignment force.

In this phase, everyone belongs and is native to the same language and culture, therefore there are no “expats”, borrowing Neely’s (2017) definition of expat “as someone who is temporarily or permanently detached from their mother tongue or home culture, while still operating in their own country.”

As companies gradually start to become more multilingual and multicultural, a growing number of their employees become either “linguistic expats”, “cultural expats” or “linguistic and cultural expats”.

Linguistic expats are those employees who, while continuing to live and work in the headquarter’s country, have to adopt another language (the new chosen lingua franca). For example, when the Japanese company Rakuten decided to adopt English as its lingua franca, all the Japanese employees in Japan became linguistic expats.

Cultural expats are those employees who live and work in a country different from the headquarter’s country, but whose native language was chosen as lingua franca. In the case of Rakuten, the cohort of English speaking employees in the US became cultural expats, as English became their lingua franca, and they had to adapt to the Japanese way of doing business. Linguistic and cultural expats, also called dual expats, are those employees who live and work in countries other than the headquarter’s country and the countries where the lingua franca is the native language. This cohort has to adopt the lingua franca as well as the culture of the company’s headquarters. There is a fourth cohort of employees, usually smaller in num. ber, who we call bilingual experts. This group of employees, regardless of where they live and work, are proficient in both the lingua franca and the culture of the headquarter’s country and one or more other languages and cultures. Usually the members of a company’s localization team are bilingual experts.

A fifth cohort of employees, we call “natives”, is made up of native speakers of the lingua franca, who are proficient in its culture, regardless of where they live and work. As companies progress on the continuum from “mono” to “multi”, and as they start to have more linguistic, cultural and dual expats, the conscious and subconscious biases of the lingua franca can start to misalign with the languages and cultures of the multilingual employees and more importantly of the global users of the company’s products and services.

This is most apparent within companies based in English speaking countries that use English in their “mono” phase as well as their lingua franca in their “multi” phase, and in which there is a high percentage of “native” employees. The business dominance of the English language, compound ed by the practices and successes the company had in its “mono” phase could potentially lead to varying degrees of blind-spots regarding other languages, cultures and local practices. One of the reasons for this misalignment is that, during the “mono” phase, a lot of linguistic and cultural nu- ances were assumed, and didn’t need further explanations. This changes in the “multi” phase, in order to properly localize the products and the internal communications.

World Wide Wisdom

Research Report 2023

It is possibile to improve the understanding between people that speak different languages and thus improve their ability to do things together in a smarter way? Can it be that a multilingual group is able to do better things? In order to answer to these questions we need to take into account how groups of people think and work together and how their collaboration can be improved.

Get Your Copy Now!The benefits of diverse teams

All companies should ensure that all of their employees feel a sense of inclusion and belonging, regardless if they are natives, linguistic expats, cultural expats, dual expats or bilingual experts.

There is a growing body of research showing the benefits of diverse teams in terms of better decision making, reduced bias, innovative thinking, creativity, problem solving, and driving market growth. Companies have discovered that diversity is good for business. This in part has led a growing number of companies to establish DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) programs.

Most DEI programs focus on a ethnocentric view of diversity usually based on a headquarter-centric view of race, age, gender, sexual identity, disability, and ethnicity, and usually at the leadership level. The 2015 McKinsey “Why diversity matters” research states the need to expand the idea of diversity and that “diversity beyond gender and ethnicity/race (such as diversity in age and sexual orientation) as well diversity of experience (such as a global mindset and cultural fluency) are also likely to bring some level of competitive advantage for firms that are able to attract and retain such diverse talent (…). Diversity matters because we increasingly live in a global world that has become deeply interconnected. It should come as no surprise that more diverse companies and institutions are achieving better performance”.

According to a 2013 research conducted by the Center for Talent Innovation: “employees who represent the company’s end user are more likely to understand that end user. Our findings show that when teams include even one team member who represents the team’s target consumer, the entire team is 158% more likely to understand that consumer”.

Indeed in today’s increasingly multilingual and multicultural world, we believe that companies, if they haven’t already, need to add linguistic and cultural diversity as a foundational pillar of their DEI programs.

This is particularly crucial as companies rely on a more culturally and linguistically diverse talent pool that includes linguistic expats, cultural expats and/or dual expats.

DEI programs can further impact a company’s bottom line by incorporating linguistic and cultural bias training and awareness. The goal is to strengthen the use of the lingua franca as a means to get things done, and in parallel also to raise awareness of the many languages and cultures within the company, reflecting the users that the company serves.

By taking a non-ethnocentric perspective, and instead matching the diversity of the company’s users, DEI programs can help ensure that companies are inclusive of all cultures, don’t fall into conformity bias, and in this way not only help employees but also help drive business growth.

Adopting a “foreign” lingua franca

Some companies realize, during their corporate evolution, that their original lingua franca no longer helps the business and actually might hinder its business growth.

As we saw earlier, research shows that 52 percent of multinational companies have adopted a language different from that of their originating country in order to better meet global expansion and business needs. Further, all the companies in the study selected English as their lingua franca.

This was the case when Air France in 2004 took over and merged with the Dutch airline KLM.

Similarly when Germany’s Hoechst and France’s Rhône-Poulenc merged in 1998 to create Aventis, then the fifth largest worldwide pharmaceutical company; the new firm chose English as its operating language over French or German. Merloni, an Italian appliance maker, adopted English to further its international image, which gave it an edge when acquiring Russian and British companies. The list goes on.

Probably one of the most studied cases of a non-English speaking company that decided to stop using its original lingua franca (Japanese) and instead start using English as its lingua franca is Rakuten.

In 2010 Hiroshi Mikitani, the CEO of Rakuten, Japan’s largest online marketplace, mandated that all business, from official meetings, to presentations, documents, internal emails and cafeteria menus, be in English.

His decision to use English as a lingua franca faced tons of criticism internally and externally because, at the time, nearly all of Rakuten’s staff did not speak English.

The decision was personally made and very vocally supported by Mikitani and based on his idea that to compete, Rakuten and all its employees had “to speak the language of the market – and that language is English. Though the number of native English speakers is dwarfed by the number of, say, native Chinese speakers, English is the language of global business.”

The adoption of English as a lingua franca at Rakuten was not an easy task and caused growing concerns among the non-English speakers. During the first year of the program, Rakuten left it up to each employee to improve their English, as long as they could pass a TOEIC (Test of English for International Communication). After realizing the progress was dismal, Rakuten started heavily promoting and offering free-English classes, and a variety of support mechanisms. Mikitani himself would continuously reinforce the value of using English as the lingua franca, in weekly company meetings and other forums.

Ultimately the program was a success and after the first two years more than 90% of the employees had passed the TOEIC.

The success of the program had deep and wide positive business implications.

It helped Rakuten expand its business globally, by rapidly acquiring companies and starting joint ventures in multiple countries. During this time Rakuten acquired EBates in the United States, PriceMinister in France, the Israeli messaging app Viber, the Canadian e-reader manufacturer Kobo, and bought stakes in the American ride-hailing app Lyft and online scrapbooking site Pinterest, just to name a few.

In Mikitani’s words “the fact that we all communicated in English smoothed these transitions, as the acquired companies’ management did not get the sense that a foreign company had taken over.”

Hiring more global talent was one of Mikitani’s goals. ”Japan’s population is aging. Our economy is slowing. We are not producing enough coders and digital gurus. The only way we can catch up and restore growth and dynamism is by looking outside our borders for talent. For that, we have to be speaking English.”

Indeed within a year of the program, a non-Japanese executive, and English-only speaker, was named head of a very large and highly visible engineering group in Japan. After 5 years, 81% of new engineers, representing 45 different nationalities, joined Rakuten’s headquarters. During this time Rakuten increased its workforce by 60%, and this growth would have not been possible without establishing English as a lingua franca, allowing Rakuten to tap into the larger pool of graduates and professionals who are proficient in English.

Global knowledge sharing was positively impacted. As Mikitani said, a Rakuten “employee anywhere in the world can pick up a phone and get an immediate answer, instead of working through a translator.”

It also helped change Rakuten’s internal culture. In Mikitani’s words “a new casual vibe permeates our office, with employees happily shunning the monotonous navy suit typical of the Japanese workplace. This diverse and modern approach is breathing new life into a moribund business culture.”

Mikitani also realized that the use of English might change some Japanese social attitudes stating that “the language has few power markers. Its use can therefore help to break down the hierarchical, bureaucratic barriers that are entrenched in Japanese society and reflected in Japanese conversation, which could boost efficiency.”

Working in multilingual and multicultural teams

No matter if a company sticks to its original lingua franca or adopts a foreign lingua franca, as companies grow and expand globally, they will have more and more employees and managers that are, or become at some point, either linguistic expats, cultural expats, dual expats or bilingual experts.

Obviously as each company is different and in a different stage of their own evolution from “mono” to “multi”, there is no single solution that works for all companies and all people. However here are some basic tenets that could help companies, leaders, people managers and employees on this journey.

Grow from an ethnocentric to a multilingual and multicultural perspective

To succeed in any role and particularly in the headquarter corporate world, all employees need to master the language and culture of their company. In parallel it helps to take a less ethnocentric perspective on language and culture, and understand and accept that other people might have very different languages and cultures, and they personally come with their own baggage of conscious and subconscious biases and their own different degrees of self-awareness.

Detect and avoid conformity bias. Conformity bias occurs when people feel pressured to agree with everyone else. This leads to groupthink among peers or to HIPPO (highest income paid person’s opinion), in the case of people in positions of power. Particularly in group meetings allow space for all members to participate, particularly those who tend to not speak up in public. Leaders should strive to get as diverse linguistic and cultural perspectives as possible, particularly when discussing matters that impact multilingual and multicultural customers.

Expand our empathy

While empathy should be practiced by everyone, it needs to be expanded to account for the diversity in multicultural teams. This means that all employees should start becoming more self-aware of their own linguistic and cultural background and experiences that have shaped their perspectives, values, attitudes, conscious and subconscious linguistic and cultural biases, plus verbal and non verbal ways and style of communication.

Active listening, flexibility, patience and humility are key elements for managers and employees to efficiently operate in complex multilingual and multicultural teams.

Don’t mistake linguistic proficiency for professional proficiency. A common unconscious bias that everyone should avoid is to equate a person’s linguistic skills with their professional skills. While communicating properly is a key part of a person’s role, their communication skills in one language might still be developing, while they have already mastered their craft using another language. Linguistic and dual expats, who are still developing their lingua franca skills, might be seen as less capable and therefore might be impacted by either not being involved in key business decisions and or not being valued/promoted in line with their professional skills.

Deepen our communication skills

Everyone should strive to speak more clearly and plainly. The goal is not to “dumb” down the conversation, but to be able to clearly present even complex ideas and thoughts in the lingua franca that everyone can understand.

Pay attention to all forms of communication, as people communicate in many different ways, visually, vocally and verbally. According to Mehrabian’s 7-38-55 communication model, 7% of the meaning of feelings and attitudes takes place through the words we use in spoken communications, while 38% takes place through tone and voice and the remaining 55% from the speaker’s body language and specifically facial expressions.

All of us use, and should be mindful of, language-specific and culture-specific language, vocabulary, metaphors, idiomatic expressions and slang. We rely on them because they often carry a deeper and powerful meaning. However their meaning might confuse the “expats” in our teams who are simply not aware of them and/or the depth of their cultural meaning. We should not refrain from using them, however if we use them, we should be more sensitive to how these will land with people from different cultures. One tactic is to explain them. This way not only we can be more inclusive, but we can also act as a cultural ambassador of our language/culture.

Remember that stereotyping can be a dangerous mental shortcut. While gross generalizations about people from a specific culture and language abound all around us, we need to always remember that every person is a unique human being that we need to get to know before we make assumptions about them.

Humor is a powerful way to bond, build trust and engagement. However, since often it’s based on specific linguistic and cultural context and nuances, we should try to calibrate our humor to our audience, and try to find humor in things that are more universally relatable and/or more relatable to our specific audience.

Learn how to adapt and localize and not just translate our native communication, style and tone to the lingua franca we are operating in. Directly and literally translating from our native language and culture sometimes could lead to even more confusion. The more we become proficient in appropriately mapping the meaning of what we want to convey into the lingua franca, the more we will help communicate with our multilingual and multicultural colleagues.

Invest in linguistic and cultural understanding

Companies should proactively support those who are learning the lingua franca and its culture. As we saw with Rakuten, this played a big role in their successful move to English as lingua franca.

Be curious about other people and their cultures. Empathy is built on a deep understanding of the other person. Spend time to genuinely know someone.

Start learning a new language. A great way to learn a culture is to learn its language. Learning a language also helps grow our awareness of our own ethnocentric conscious and subconscious linguistic and cultural biases.

Start getting immersed in a new culture. It’s easier to learn a culture than to learn a language. If we don’t have time or interest in learning a language, then we can learn more about a culture. We can do that in many ways, including through their food, traditions, history, movies, TV shows, authors and artists.

Don’t make our customers feel like expats

While companies need to anchor in a lingua franca, they should avoid falling into the trap of exporting the linguistic and cultural biases of the lingua franca to the external languages and cultures they support. The danger companies face, if they don’t properly address this, is that the conscious and subconscious linguistic and cultural biases of the lingua franca will appear in the company’s products, marketing and customer support. This is when companies “ship” their lingua franca and their culture. When this happens, then the company’s very users will become either linguistic expats, cultural expats or both. This in turn has a very high potential of negatively impacting a company’s brand, image, sales, and conversions.

Conclusion

As companies grow from a “mono” to a “multi” phase they experience the tension of being grounded in a strong lingua franca that allows the business to internally operate and communicate efficiently, quickly and with purpose, versus the need to accommodate a growing number of “expat” employees, and multilingual and multicultural users globally.

Being aware and addressing this tension is not only important for the well-being of the employees, but in turn it’s vital for the well-being and continued business growth of the company.

This is particularly problematic and happens more often in English-speaking countries, and in headquarter-centric companies with a heavy top-down type of management. These usually are companies in which most and/or the most important decisions are made by a few people and teams in the headquarters who are only proficient in the lingua franca. Often in these cases the lingua franca can strongly and negatively influence the company’s external language and culture.

This seems to be less of a problem in non headquarter-centric companies and/or in companies where decisions impacting multilingual and multicultural customers are delegated to functional localization experts in headquarter and regional teams.

One of the business benefits of companies, like Rakuten, that adopt a foreign lingua franca, is that by making each employee an expat (of one kind or the other) it sensitizes the company’s leaders and employees of the linguistic and cultural commonalities and differences. It makes these companies more aware of language and culture and this in turn helps them adapt their products to better cater to the unique expectations of their growing international audience of users.

These matters are increasingly more important in today’s post-COVID19 working environment, where companies are more open to remote work, and are relying on a more globally distributed and diverse workforce.

Multilingual and multicultural employees make better companies, that in turn are better able to cater to the company’s growing multilingual and multicultural customers. It’s the job of each leader, people manager and employee to be aware and help the company evolve.

It’s a virtuous cycle that starts with linguistic and cultural awareness and empathy.

Salvatore Giammarresi

Head of localization at Airbnb

Salvatore Giammarresi holds a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics and is a leading expert in localization and global operations. He’s held leadership roles at Airbnb, PayPal, and Yahoo, and is a published author.

Bibliography

A.W. Harzing and M. Pudelko, “Language competencies, policies and practices in multinational corporations: A comprehensive review and comparison of Anglophone, Asian, Continental European and Nordic MNCs”, Journal of World Business 48, no.1 (2013): 87-97.

S.A. Hewlett, M. Marshall, L. Sherbin, T. Gonsalves, “Innovation, diversity and market growth”. Center for Talent Innovation, 2013

T. Mughan and G. O’Shea. “Chapter 6. Intercultural Interaction: A Sense-making Approach”. In The Intercultural Dynamics of Multicultural Working, edited by M. M. Guilherme, E. Glaser and M. del Carmen Méndez-García, Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, 2010, pp. 109-120.

T. Neeley, The Language of Global Success: How a Common Tongue Transforms Multinational Organizations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017

V. Hunt, D. Layton, S. Prince, “Diversity Matters”, McKinsey & Company, 2015

Photo credit: Deepmind, Unsplash

Photo credit: Zhang Kaiyv, Unsplash