Global Perspectives

October 2024

Key Statistics

- English is the most spoken language worldwide in 2023 (Statista).

- UK ranked second most powerful country in ‘soft power’. (Brand Finance, 2024).

- It is the 6th largest economy in the world and the 2nd largest in Europe in terms of GDP (Global Peo Services, 2024).

- Ranked 5th on a list of 133 countries globally in the Global Innovation Index (2024).

- United Kingdom is 12th in the overall Prosperity Index rankings (The Legatum Prosperity Index, 2023).

God Save the Queen

The death of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022 brought to an end what was the longest reign in the United Kingdom, spanning seventy years of history. Years in which the world, still shaken by World War II and the Cold War, was profoundly transformed.

The stories of the reign of Elizabeth II and the Commonwealth are deeply intertwined. The Queen began her reign in 1952 at the age of 25 and took over, after the sudden death of her father, in a particularly delicate phase of the British Empire. In fact, when she ascended to the throne, the Empire had already shed its former name: the last sovereign to bear the title of emperor was his father, George VI, who lost the title after the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947. Although in previous decades and centuries many states – such as the United States, Canada and Australia – had gained independence, the loss of the Indian subcontinent has deeply undermined British rule. Indeed, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh represented the “pearl of the crown” for their strategic value from a military, geo-political, and economic point of view. Also, the independence of these states pushed the other colonies to fight for independence and marked – in general – the decline of British rule over the world and the emergence of a new global order.

Thus, Queen Elizabeth witnessed three decades marked by the decolonization of over 50 countries. In just a few decades, Great Britain had dissolved and the Queen had to deal with this process intertwining the new international relations, in the name of the new values of self-determination and democracy. Over the years, the Commonwealth of Nations has emerged as a strategic tool to maintain British influence in former colonies, while also mitigating the impact of decolonization.

The decline of the British Empire and the Rise of the Commonwealth

Source: The Washington Post

The Commonwealth today is an international organization of 56 countries, almost all united by past membership of the British Empire – except for Rwanda, Togo, Gabon, and Mozambique. Among these, moreover, 15 countries are part of the “Commonwealth Realms” (i.e. countries that recognize the British monarch as head of state), including Australia, Canada and New Zealand (Wikipedia). Covering all the continents of the world and having a population of over 2.5 billion people, of which over 60% are in the under 30 range, it turns out to be a real global power (The Commonwealth). It is unique in its type of post-colonial relations and in its balance between voluntary cooperation and a shared imperial legacy, managing to represent a meeting point for many cultures and national identities. Specifically, it is estimated that there are about 2,300 languages spoken and over 10 major religions – including Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and many others – coexist peacefully among the different member states (Commonwealth Round Table). For the Commonwealth to function as an effective and cohesive multicultural meeting point, it requires a strong and unifying symbol—one that Queen Elizabeth has exemplified throughout her seventy-year reign. Visiting over 100 countries, promoting respect for local cultures and traditions, and supporting a peaceful decolonization, she has managed to maintain a persistent influence of the United Kingdom on the former colonies.

With Charles III becoming king, he must balance maintaining the Commonwealth’s relevance with embracing multiculturalism. As countries reassess their ties to the monarchy and colonial past, Charles faces a more aware and critical public. This stance has sparked a heated debate about how to address the colonial past. It clashes with the diverse and evolving nature of modern Britain, highlighting the challenges of reconciling a troubled history with today’s multicultural society.

A World of Englishes

English is the global lingua franca, reaching even the most remote corners of the world and dominating key areas like business, governance, research, and international culture. Its prominence in global communication stems from centuries of geopolitical shifts, colonial expansion, and cultural influence. In today’s Fourth Industrial Revolution, English continues to solidify its influence, particularly online, where it accounts for 52.1% of all content (Statista), making it the most widely used language on the Internet.

Currently, 1.35 billion people speak English, representing 17% of the global population (Perply). It holds official status in 75 countries, 55 of which recognize it constitutionally. With 527 million native speakers, it ranks as the 3rd most spoken language worldwide (The Chairman’s Bao). Moreover, English is a required subject in the education systems of 138 countries, making it the most studied foreign language (Perply). Experts even predict that by 2050, more than 2 billion people will speak English.

However, while English may seem like a unifying force, it is actually a mosaic of dialects, accents, and variations, shaped by the diverse histories of those who speak it. British colonialism gave rise to many ‘local’ Englishes, and today, there are over 160 officially recognized English accents worldwide (Speak Blog).

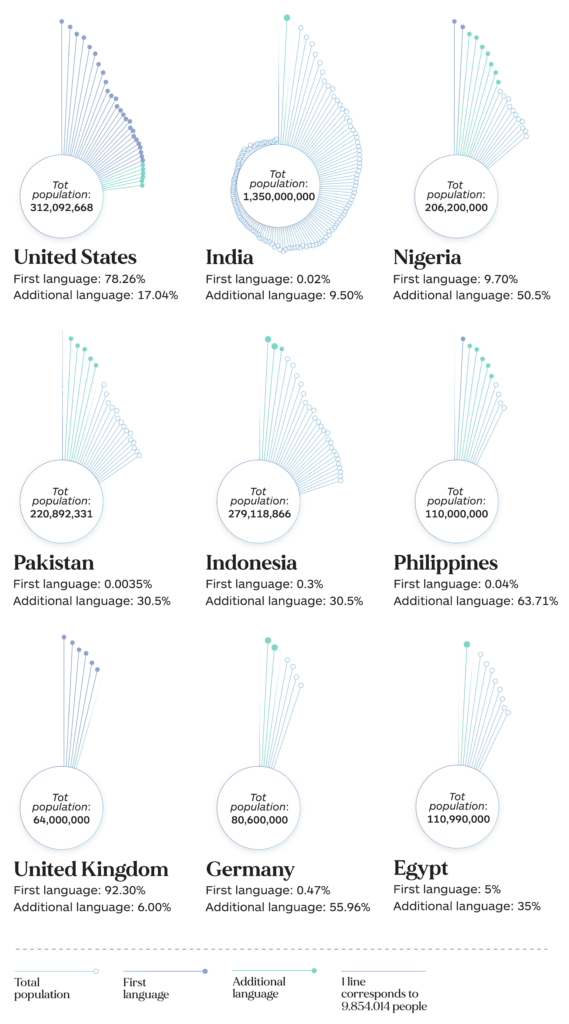

Countries with the largest English-speaking population, 2022

Source: Wikipedia

For instance, Received Pronunciation (RP), commonly known as ‘Queen’s English,’ represents the standard of British English, characterized by precise articulation and the omission of the final ‘R’ sound (non-rhotic). Although this accent is often linked with the British upper classes, it is just one of many variations within the UK. The Scouse accent from Liverpool reflects the diverse influences of sailors from different countries, while the Geordie accent from Newcastle has a notable Scandinavian touch. In London, the linguistic landscape is continually evolving, adding to the rich tapestry of regional accents. Cockney English, once the accent of the East End working classes, has been partially replaced by Multicultural London English (MLE), a linguistic phenomenon that blends youth slang with African, Caribbean, and Asian dialects. Today, London youth commonly use terms like ‘nang’ (from Bengali) for ‘cool’ or ‘dupa’ (from Polish) for ‘girl’, demonstrating how English absorbs influences from every corner of the world.

Looking further afield, in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, English coexists with minority languages that symbolize cultural and political resistance. In Scotland, accents like Glasgow or Highlands showcase the influence of Scottish Gaelic, spoken by around 57,000 people (Scotland’s Census). In Wales, over 29% of the population speaks Welsh (Statista), while in Northern Ireland, the Irish language is experiencing a renaissance, with a 10% increase in speakers over the past decade. These linguistic movements are often linked to a demand for political autonomy, with language seen as a crucial tool for reaffirming sovereignty and cultural identity.

English, like many languages, is a constantly evolving entity. Although it is often seen as a standard, unified language, it encompasses a vast array of expressions. As sociolinguist Sebastian Rasinger notes, “whether we’re talking about conquerors or the conquered, people have always left their mark on the English language.” Thus, English is not only the language of the world, but also a world of languages.

From a global perspective, North America boasts 24 recognized officially different accents, including the iconic New York accent and the Southern drawl of the United States. In Canada, Canadian English emerged from a fusion of British and American influences, while in Hawaii, Pidgin Hawaiian developed a blend of English, Hawaiian, and Asian languages.

In Africa, 24 countries have embraced English as their official language, including Kenya, Ghana, Uganda, and South Africa. However, the majority of people in these nations also speak local languages or use English only in formal settings, resulting in distinct and unique accents that reflect their daily interaction with their native languages.

However, also in Australia, New Zealand, India, Singapore, and many other countries, English has evolved into local forms that make it distinctly different from the English spoken elsewhere. For example, in Australia, the term ‘cigarettes’ is transformed into ‘durries’, while in South Africa it becomes ‘stokkies’. These small examples of linguistic variation demonstrate how global English encompasses a multitude of linguistic worlds.

English, like many languages, is a constantly evolving entity. Although it is often seen as a standard, unified language, it encompasses a vast array of expressions. As sociolinguist Sebastian Rasinger notes, “whether we’re talking about conquerors or the conquered, people have always left their mark on the English language.” Thus, English is not only the language of the world, but also a world of languages.

Disunited Kingdom?

Once a symbol of diversity and multiculturalism, the United Kingdom is now grappling with growing disunity, driven by deep political and social divisions, many of which stem from the issue of migration.

In fact, immigration has had a significant impact not only on the cultural sphere, but also the economic one. According to the Migration Observatory, foreign workers now make up 21% of the British workforce, with a particularly strong presence in crucial sectors such as public health, research, information technology, and communications. At the same time, a clear divide is evident in the sectors where migrants are employed. While those from India, Oceania, and North America typically hold highly specialized roles, migrants from the European Union often occupy positions with less specialization, such as cleaners, waiters, and packers.

In terms of demographics, approximately 16% of people in the United Kingdom were born abroad. The primary nationalities of origin include India (965,000), Poland (841,000), Pakistan (654,000), and Romania (558,000) (Migration Observatory). Furthermore, the presence of migrants varies significantly across the country’s regions. In London, migrants make up 37% of the population, a figure that jumps to 44% in smaller cities like Slough. This uneven distribution has made some areas of the country more accustomed to diversity, while others, particularly rural areas, have experienced immigration as a foreign phenomenon, contributing to a growing polarization between urban centers and suburbs.

The significant percentage of the country’s migrant population led to increased pressure on the nation’s infrastructure, particularly in terms of the housing crisis. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has projected that the British population will reach 70 million by 2026, a decade earlier than anticipated, with a steady increase to 73.7 million over the following decade. Net migration will account for over 90% of this population growth. This overcrowding is putting a strain on the country’s housing system, which is currently struggling to meet the growing demand. In fact, projections suggest that addressing this increase will require new schools, hospitals, transportation infrastructure, and, most importantly, new homes.

Source: Statista

To fully understand this fragmentation and the multicultural composition of British society, it’s crucial to examine the United Kingdom’s past. For instance, shortly after World War II, the country was in a state of reconstruction and faced a dire need for manpower. Afro-Caribbean communities began to arrive en masse, drawn to the job opportunities offered by a growing economy. Additionally, between 1951 and 1961, the number of people born in the West Indies and living in the United Kingdom increased from 15,000 to 172,000. Furthermore, the fall of communism in 1989 triggered another significant wave of migration, this time from Eastern Europe. Polish migrants, in particular, began arriving in steady numbers, especially after Poland joined the European Union in 2004. The freedom of movement allowed them to fill key roles in construction and service, providing essential labor and skills that became vital to the British economy.

Despite a history where immigration was seen as an opportunity, many of today’s political tensions stem from the failure to adapt infrastructure to demographic changes. The populist pledges to control immigration, made by politicians like David Cameron and backed by the pro-Brexit campaign, have fueled the belief that it was possible to ‘regain control’ and ease the strain on public services. The reality, after years of unfulfilled promises, has led to a growing disillusionment and a sense of betrayal, not only among the native population but also among many migrants who find themselves living in an increasingly hostile country.

The fractures within the United Kingdom expose long-standing social and cultural divides. Immigration, once a cornerstone of the country’s diversity, has become a focal point of division. Populist movements have seized on these fears, framing immigration as the root cause of issues like unemployment and housing shortages. Yet, focusing solely on migration overlooks the complexity of a nation whose identity has long been intertwined with diversity. The real challenge lies not in closing borders, but in rediscovering the unity that once drew strength from its differences.

Wind of Change

Brexit stands as one of the most complex and contentious episodes in recent British history. Four years on since the official break-up between the EU and United Kingdom, the effects have rippled far beyond the borders, reshaping the political landscape and economic realities.

Upon closer examination, despite the Leave campaign’s promises of greater independence and economic prosperity, the reality proved to be much more complex. In fact, one of the most noticeable impacts in the economy was the loss of jobs. According to a Cambridge Econometrics report, the exit from the EU is projected to result in the loss of approximately 1.8 million jobs by 2023, with a significant impact on key sectors such as finance and construction.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the UK’s GDP has undergone a significant slowdown. In 2023, the country saw a 6% decline in its gross value added (GVA), resulting in a loss of approximately £140 billion compared to a scenario where the UK remained in the EU (Mayor of London). Brexit has also exacerbated the cost-of-living crisis, particularly in terms of rising food prices. Around 30% of the food price increase between 2019 and 2023 can be directly attributed to Brexit, which has complicated trade flows and increased costs for importers and producers (Centre for Economic Performance).

The future perspective remains equally uncertain. According to forecasts, by 2035, the UK’s GDP is expected to be 10% lower than if the country had remained in the EU, resulting in an economic loss of over £300 billion (Cambridge Econometrics). This will further hinder the UK’s growth potential, hindering its ability to attract investments.

While the formal decision to exit the European Union was made in the 2016 referendum, its origins stretch back to decades of fraught relations between London and Brussels. In fact, the UK’s relationship with Europe has always been a balancing act, caught between the economic allure of European integration and deep-seated fears of losing national sovereignty.

Firstly, the UK’s entry into the European Economic Community in 1973 did little to resolve these internal conflicts. Indeed, although a 1975 referendum showed strong support for remaining in the EEC with 67% of the vote, debates continued unabated. Furthermore, the 1980s witnessed a dramatic shift when Margaret Thatcher, who had previously supported European integration, adopted a hardline stance in her famous 1988 Bruges speech. There, she denounced the notion of a political and federal Europe, a moment that catalyzed the rise of Euroscepticism in Britain.

The 1990s brought a surge in Euroscepticism with the introduction of the Maastricht and Amsterdam treaties. The UK’s numerous opt-outs, including its decision not to adopt the euro, underscored a growing sense of isolation. This discontent simmered beneath the surface, particularly among conservatives. Despite Tony Blair’s efforts to mend fences with Brussels, Nigel Farage with UKIP capitalized on mounting public discontent, especially concerning immigration, gaining significant traction in the political landscape.

United Kingdom

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!The pivotal moment arrived in 2016, when David Cameron, in an effort to resolve the European issue once and for all and keep his party united, called for a referendum. On June 23 of that year, 51.9% of voters cast their votes to exit the EU. The margin of victory, while decisive, was narrow and exposed a country divided along geographical, social, and generational lines. England and Wales opted for ‘Leave’, while Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the cosmopolitan city of London sided with ‘Remain.’ This outcome raised concerns about the unity of the United Kingdom itself, with Scotland immediately considering a second referendum for independence, with the aim of remaining within the EU.

Brexit was, therefore, not merely a political decision, but rather a momentous transformation for the United Kingdom. It has brought to light the underlying tensions between those who sought a return to national sovereignty and those who saw the EU as an economic and political opportunity. Today, the country remains in uncharted waters, facing economic and social challenges that could shape its future for decades to come.