Global Perspectives

(LA) FLORIDA

1 out of 3 households in Florida speaks a foreign language at home

Besides Alaska, Florida is the only state in the United States of America that borders the Ocean on three sides: the east; the south; and the west. The sea routes of this wealthy and populated state, 21 600 000 people with a median household income of USD 67 917 – USD 80,610 is the median household income U.S. (Data USA, 2022a) – has carried a constant flow of trade, music, art, food, and human beings from Mexico, the Bahamas, and, more importantly, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean world. The consequent influences on Florida culture span from Europe to Mesoamerica and from Africa to Asia.

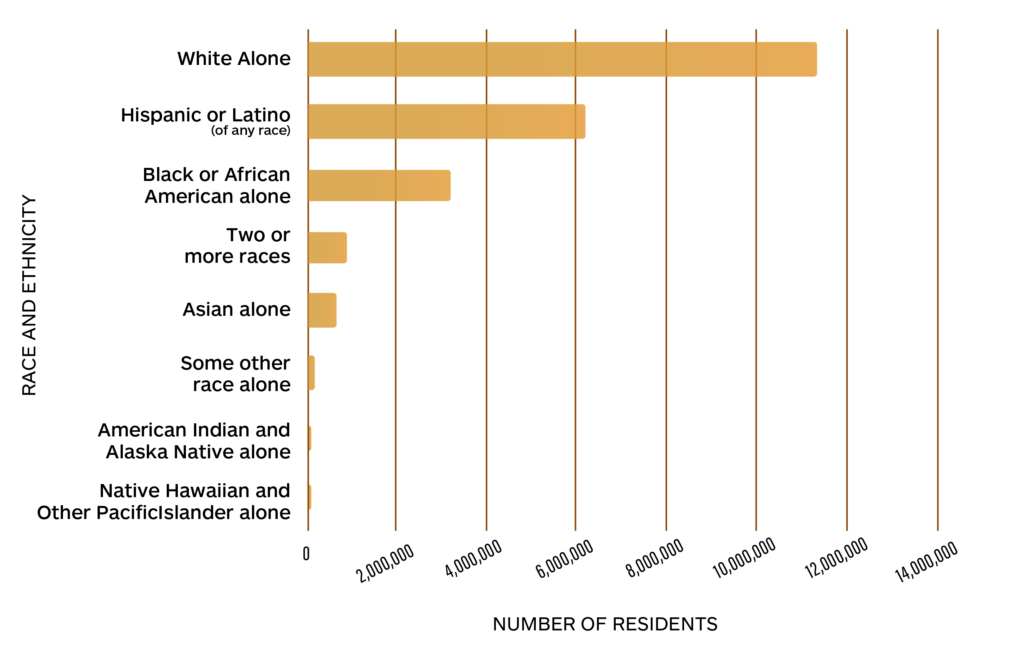

Resident population of Florida in 2023, by race and ethnicity

Source: Statista

A continuous flux of visitors, immigrants, and newcomers adds to the state cultural lush, to the extent that the public education system found more than 200 languages being spoken privately as first language in the state (MacDonald, 2004). More impressively, according to the American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, almost 1 out of 3 households in Florida speaks a foreign language at home (Data USA, 2022b). Currently, these languages include Spanish (22.2%), Haitian (2.12%), and Portuguese (0.732%) as well as French, Chinese, Arabic, Tagalog, Vietnamese, German, Russian, and Italian, among others (Ibidem).

“We really learn our language not from our families, but from speech communities around us.”

– Said Phillip Carter, FIU professor of English and linguistics and affiliate of the university’s Cuban Research Institute, who led the research.

English-Spanish: A polymorphic influence

The aforementioned geographic, historical, and cultural elements play a morphing role in the everyday language spoken in Florida, especially in the south. According to Professor of Linguistics Phillip M. Carter, Florida has featured “one of the most important linguistic convergences in all of the Americas” (Carter, 2023). This de facto English-Spanish bilingualism has produced phenomena such as Spanglish and linguistic calques, derived from Spanish expressions, that have permeated into the so-called English of South Florida.

The most noticeable effect of these influences on English is the phenomenon of calque. A calque is “a sort of a loan translation, where you don’t borrow the word, but you borrow the concept and you translate it into the target language” (Rascoe, 2023).

| English of South Florida expression | Standard English | Spanish calque or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bueno | Well | Bueno |

| Bring | Has/Carry | Traer |

| Chanx | Flip-flops | Shortened form of chancletas |

| Could | Can | Podría |

| Drink a pill | Take a pill | Tomar una pastilla |

| Eating shit | Doing nothing important or something foolish | Comiendo mierda |

| For buy | For buying | Para comprar |

| Get down from the car | Get out of the car | Bajar del carro |

| Go | Come | Pasar |

| He invited me for | He invited me to | Él me invitó para |

| Irregardless | Regardless | Independientemente |

| Make a party | Throw a party | Hacer una fiesta |

| Married with | Married to | Casarse con |

| Marta recommended me | Marta recommended that I | Marta me recomendó |

| Meet | Beef | Carne |

| Open a hole | Tear a hole | Abrir un hueco |

| Pero like | Yes but | Pero como |

| Porfa | Please | Por favor |

| ¿Qué bolá?/¿Qué vuelta? | What’s up? | |

| Que cute | How cute | Que lindo |

| Thanks God | Thank God | Gracias a Dios |

| Thinking in | Thinking of | Piensando en |

| Threw a photo | Took a photo | Tiró una foto |

| Yes, I want | I do | Sí quiero |

Sources: Carter, 2022; Carter and D’Alessandro Merii, 2023; Munzenrieder, 2014b

Not just Spanglish: Cubonics, and Haitian Creole

Spanglish is a combination of Spanish and English, with different versions throughout the U.S. and other countries. Antonio Martínez defined Spanglish as “code-switching” and a “hybrid language practice” rather than a creole, a dialect, or an ethnolet (Martínez, 2010). A politically active linguist, Zentella, stressed that English-Spanish switching is rather “a creative style of bilingual communication that accomplishes important and conversational work” (cited in Lipsky, 2008, pp. 48–49).

“All dialects have rules every bit as rigorous as those of the standard dialect, which is usually determined by the most influential social class. So speaking with a Southern, Brooklyn, or Black accent is not a matter of breaking the rules of grammar but of speaking with slightly different ones. So, if you change your accent, remember, the reasons are all economic or social; they should not be linguistic.”

(Beard, 2024)

The specific form of Spanglish spoken in Southern Florida is called Cubonics by merging the terms “Cuban” and “Ebonics.” Cubonics is so widespread in Miami that courts require specific translators for it (de Jongh, 1991). Its characteristics are the following: 1) it uses Cuban idioms within English phrases; 2) it has a Cuban inflection of English words; and 3) it translates some Cuban idioms directly into English.

| Cubonics expression | Standard English |

|---|---|

| Bibaporrú | Vicks VapoRub |

| Coco No Grow (place) | Coconut Grove |

| Copiúti | Computer |

| Cora Geibo (place) | Coral Gables |

| Da sol | That’s all |

| El colí | The college |

| Esláy | Slice |

| Estick (personal name) | Steve |

| Guarejao | Warehouse |

| Guasápeninmeng | What’s happening, man? |

| Jonle | Homeless |

| La Casina | Lacquer Thinner |

| Lató | Laptop |

| Papa Yon | Papa John’s |

| Tirate al Mar (place) | Miracle Mile |

| Transpoteíchon | Cheap Car |

Source: Katel, 2013

On the other hand, Haitian Creole, one of the two official languages of Haiti, is a French-based creole language spoken by 10 to 12 million people worldwide, making it the 2nd most important creole language in the world. Even if its extent is not comparable to that of Spanglish, Haitian Creole is the 3rd most spoken language in Florida.

| Haitian creole expression | Standard English | French origin |

|---|---|---|

| Byen venu | Welcome | Bienvenu |

| Bonjou | Good morning | Bonjour |

| Ki kote ou sòti? | Where are you from? | D’où sortie-vous? |

| Koman ou rele? | What’s your name? | Quel est votre nom? |

| Larivyè | River | La rivière |

| M rele… | My name is… | M’appelle… |

| Sak pase? | How are you? | Comme ça va? |

| Tèt | Head | Tête |

| Vyann | Meat | Viande |

Source: Sonny, 2022

Everyday slang

Florida slang does not necessarily emerge from bilingualism or calques. It has much to do with the typical lifestyles (Munzenrieder, 2014a), which are generally considered “weird” by most other Americans because of their patchwork mix. Leisure and tourism, immigration, retiree habits, and rurality, but also Southern American dialects all contribute to mold slang expressions of everyday life.

| Florida slang expression | Standard English |

|---|---|

| Airboating | Riding on a gliding flat-bottomed boat |

| Beach bum | Relaxed beach-goer |

| Bro | Anyone being addressed |

| Cafecito | Cuban espresso |

| Casa Yuca/Casa de caraco | Somewhere extremely far and out of the way |

| Conch fritters | Deep-fried seafood appetizer |

| Cuban sandwich | Grilled sandwich with roasted pork, ham, Swiss cheese, pickles, mustard, and Cuban breadFlorida cracker |

| Florida cracker | Native white Floridian (often derogatory) |

| Gator | Alligator |

| Palmetto bug | Big and fast cockroach, often identified with the American cockroach (Periplaneta americana)—expression shared with other Southern states such as South Carolina |

| Pata sucia | A woman walking barefoot in public |

| Pastillera fest | A rave with a lot of drugs |

| Pookie-head | Consumer of a high quantity of ecstasy drug |

| Refi | Fresh off the boat (derogatory) |

| Salt life | Enjoying coastal leisure activities (surfing, fishing, etc.) |

| Shelling | Searching for seashells on the beach |

| Snowbird | Seasonal resident or tourist |

| Super | Very, very much, a lot |

| Supposably | Supposedly |

| Tiki-tiki music | Fast-paced/techno music |

| Took the light | Running a yellow light in traffic |

| What dey do | How are you? |

Sources: Nautilus, 2023; Munzenrieder, 2014b

The Miami dialect

Moreover, in Miami, phrases that might sound unusual to most English speakers have become part of everyday speech. Expressions like “get down from the car” instead of “get out of the car” reflect a direct translation from the Spanish “bajar del carro.” Similarly, Miamians might say “make a party” rather than “throw a party,” translating from the Spanish “hacer una fiesta,” or “married with” instead of “married to,” based on the Spanish phrase “casarse con.”

“get

out ofthe car” > bajar del carro > “get down from the car”

“

throwa party” > hacer una fiesta > “make a party”

What’s fascinating is how Miami’s homegrown dialect continues to evolve. While some expressions, like “throw a photo” (from “tirar una foto”), are primarily used by the immigrant generation, others, like “married with,” are embraced by Miami-born speakers. Experiments show that Miamians are more accepting of these localized expressions than people from other parts of the U.S.

This phenomenon reminds us that language is always changing, shaped by cultural exchange and history. Take the world dandelion as an example. This flower grows in central Europe and when the Germans realized they didn’t have a word for it, they looked to botany books written in Latin, where it was called dens lionis, or “lion’s tooth.” As a result, the Germans borrowed that concept and named the flower “Löwenzahn”, a literal translation of “lion’s tooth.” Also the French didn’t have a word for the flower, so they also borrowed the concept of “lion’s tooth,” calquing it as “dent de lion.” Similarly, the English, not having a word for this flower, heard the French term without understanding it, and gradually they’ve adapted “dent de lion” into their language, transforming it into “dandelion.” This term, shaped by centuries of calques from Latin to German, French and English exemplifies how language evolves. In the same way, modern expressions from the Miami dialect, like ‘get down from the car,’ show how languages continue to adapt and evolve through cultural contact. Therefore, every phrase we use carries a story and a history of borrowed meanings and cultural fusion.

Sara Bissen

English expert linguist

Sara Bissen has built action-oriented research in relation to the rural-urban conflict. Her transnational perspective on land and dispossession has informed her transdisciplinary work on rurality—from a pre-industrial country, such as Guatemala, to the developing and post-industrial countries of Turkey and Italy, respectively. Within this frame, her work has addressed the following contemporary topics: forced migration; urban decay; transnational peasantry; urban informality; farmer suicide; and rural transformation. Through The Ruralist Body, Sara has published over 20 disseminative and scientific writings on social, economic, political, and anthropological factors from the vantage point of the rural world. Her published books include Topsoil (2015), The City Smells of Decay (2016), and This Is Not Topsoil (2024).

References

Ascoli, G.I. 1867. Studj ario-semitici, Memorie del Reale Istituto Lombardo, cl. II, 10:1–36.

Beard, R. 2024 [Consulted]. A glossary of quaint southernisms. In: alphadictionary.com. https://www.alphadictionary.com/articles/southernese.html

Carter, P.M. 2023. A new English dialect is emerging in South Florida, linguists say. Scientific American, June 14. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/linguists-have-identified-a-new-english-dialect-thats-emerging-in-south-florida/

Carter, P.M. and D’Alessandro Merii, K. 2023. Spanish-influenced lexical phenomena in emerging Miami English: Tracking production and perception. English World-Wide, 44(2): 219–250. https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.22036.car

Castro, M.J., Haun, M., and Roca, A. 1990. The official English Movement in Florida. In: K.L. Adams and D.T. Brink (eds.). Perspectives on Official English. The Campaign for English as the Official Language of the USA. Berlin, Boston, U.S.A.: De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110857092

Data USA. 2022a. Non-English Households. In: datausa.io. Boston, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/florida/demographics/languages

Data USA. 2022b. Florida. In: datausa.io. Boston, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/florida

Dictionary.com. 2020. There’s no way you’ll know all these Florida words. In: dictionary.com. Oakland, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.dictionary.com/e/florida-words/

de Jongh, E.M. 1991. Foreign language interpreters in the courtroom: The case for linguistic and cultural proficiency. The Modern Language Journal, 75(3): 285–295. https://doi.org/10.2307/328722

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. 2024. 2024 Florida Agricultural & Related Products Export Report. June. https://ccmedia.fdacs.gov/content/download/82384/file/2024-Fl-Ag%20-Export-Report.pdf

Katel, J. 2013. “Miami Cubonics”: A ten-word guide, according to Palo!’s Steve Roitstein. Miami New Times. August 12. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.miaminewtimes.com/music/miami-cubonics-a-ten-word-guide-according-to-palo-s-steve-roitstein-6471521

Labov, W., Ash, S., and Boberg, C. 2006. The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lipski, J. 2008. Varieties of Spanish in the United States. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC.

MacDonald, V.M. 2004. The status of English language learners in Florida: Trends and prospects. Policy Brief. Tempe, U.S.A., Arizona State University. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://web.archive.org/web/20140209171845/http://www.collier.k12.fl.us/ell/docs/Status%20of%20ELL%20in%20Florida.pdf

MPI (Migration Policy Institute). 2022. Florida. Language & Education. In: migrationpolicy.org. Washington, DC. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/state-profiles/state/language/FL

Martínez, R.A. 2010. Spanglish as literacy tool: Toward an understanding of the potential role of Spanish-English code-switching in the development of academic literacy. Research in the Teaching of English, 45(2):124–149. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte201012743

Munzenrieder, K. 2014a. The ten distinct states that make up Florida. Miami New Times. 10 June. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/the-ten-distinct-states-that-make-up-florida-6530661

Munzenrieder, K. 2014b. Miami slang glossary: Pero Like, It’s super-definitive, Bro. Miami New Times. April 25. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/miami-slang-glossary-pero-like-its-super-definitive-bro-6528513

Nautilus. 2023. Common Florida slang: Exploring the Sunshine State lingo. In: nautilusshc.com. Palm Beach, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.nautilusshc.com/blog/common-florida-slang

Ortvet, J. 2013. Ratchet: The rap insult that became a compliment. In: thecut.com. New York, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.thecut.com/2013/04/ratchet-the-rap-insult-that-became-a-compliment.html

Payne, K. 2023. More Palm Beach County students learning in Haitian Creole as dual language program expands. In: wlrn.org. Miami, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.wlrn.org/education/2023-09-01/palm-beach-schools-haitian-creole-language-program

Rascoe, A. 2023. A new South Florida dialect is forming in real time. NPR. Weekend Edition Sunday, June 18. Washington, DC. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/18/1182941050/in-south-florida-a-new-dialect-is-forming-in-real-time

Ricento, T. 1995. A brief history of language restrictionism in the United States. Revised version. U.S. Department of Education, Educational Resources Information Center, New York, U.S.A. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED426599

Sonny, M. 2022. The top 6 most widely spoken creole languages. In: crystalcleartranslation.com. Guildford, U.K. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://crystalcleartranslation.com/the-top-6-most-widely-spoken-creole-languages/

Vinnik, E. 2023. Linguistic expectations in South Florida. The National High School Journal of Science. October 1. [Cited 28 October 2024]. https://nhsjs.com/2023/linguistic-expectations-in-south-florida/

What is Imminent in?

A monthly deep dive to thoroughly explore a country of the world, starting from current events related to language, economy, and culture.

Discover the What’s Imminent in section