Economy + Geopolitics

November 2025

Donald Trump has just wrapped up what he calls one of the most important deals of his presidency: TikTok should soon be in American hands. Or so Trump has been claiming, because neither ByteDance nor Chinese authorities have confirmed the agreement. And that’s where the paradox begins.

The Trophy Everyone Wants

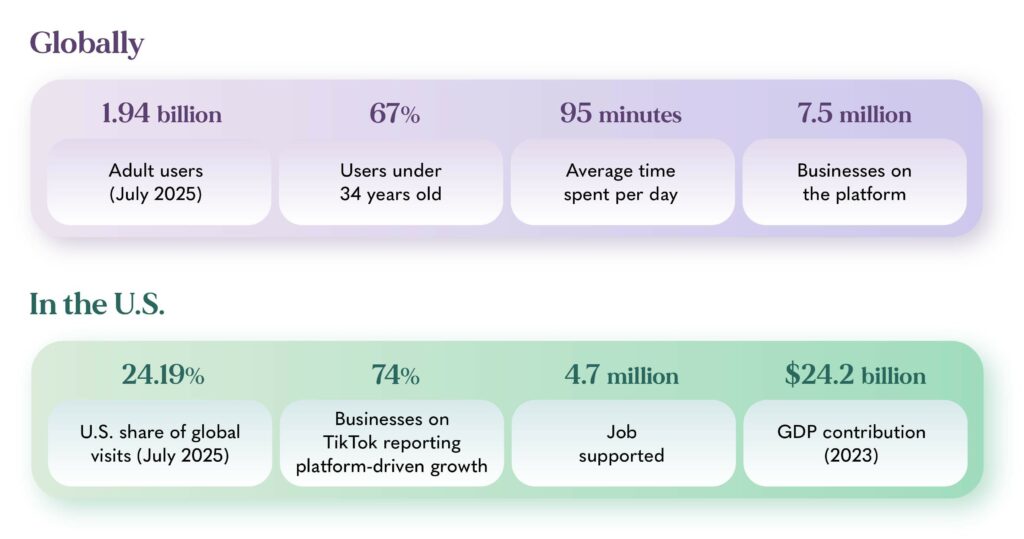

The numbers explain the obsession. TikTok has a massive global footprint, with a particularly strong presence in the United States, where millions of Americans scroll, dance, and shop every day. Most users are young—the most coveted demographic for anyone looking to shape consumption, trends, or votes.

Economically, the platform has a billion-dollar impact on American GDP and supports millions of jobs. Advertising revenue in the U.S. alone is projected at $15.53 billion. For businesses, TikTok is no joke: most companies say the app has helped them scale operations.

This is the empire Trump wants to conquer. Last month’s executive order transfers the majority of TikTok’s U.S. operations to a consortium of investors—including Oracle’s Larry Ellison, Rupert Murdoch, and Michael Dell—while ByteDance would retain only 20%. Deal valuation: $14 billion—a bargain, considering estimates for TikTok’s U.S. arm ranged from $20 to $100 billion (Wall Street Journal).

If the deal goes through, Trump and his allies would gain unprecedented leverage over the platform — from shaping its content moderation policies to deciding how user data is shared with U.S. authorities (Bloomberg). Under the plan, the group of American investors would oversee the algorithm powering TikTok’s U.S. version, with six of the seven board seats held by U.S. citizens. In practice, it would grant Washington a level of control that other social media giants have fiercely resisted for years.

TikTok vs. USA: By the Numbers

Why TikTok, Exactly?

A fair question.

Over 23% of TikTok’s content is pure entertainment—dances, memes, viral trends. Educational or political content makes up just 5%. If this is the “kingdom of superficiality,” why go so far as to ban or seize it?

Probably for three reasons—all true at once:

- Generational influence: TikTok doesn’t sell products; it sells attention. Users spend an average of 95 minutes a day on the app. Controlling what young voters see, buy, and do is pure soft power.

- Geopolitical rivalry: While Instagram and YouTube scramble to copy TikTok’s format, China still holds a potent cultural and economic weapon on U.S. soil. Social media holds incredible power over societies: that’s why TikTok is already banned in India, Iran, Nepal, and Somalia. Facebook is banned in Russia, Instagram in Pakistan, YouTube in China. Social media bans aren’t new—they’re just new to the U.S.

- Economic and technological control: Beijing’s latest five-year plan explicitly aims for technological self-sufficiency. Seizing such a significant economic lever may align with a broader U.S. effort to limit China’s dominance in algorithmic technology.

The Algorithm Problem

And here lies the heart of the paradox. TikTok works because its algorithm is disturbingly good.

It knows what you’ll like before you do. That’s what allowed it to crush giants like Meta in just a few years.

The trick is called the For You Page (The Washington Post). When you open TikTok for the first time, you have no friends, you follow no one—yet your feed is already alive. On Facebook or Twitter, you’d be staring at an empty screen. On TikTok, you’re instantly entertained and, as you scroll, the algorithm learns.

It doesn’t wait for you to hit “like.” It experiments: showing you videos it thinks you might enjoy and watching how you react. It’s a silent, constant dialogue. TikTok openly lists what it uses to personalize your feed: likes, comments, hashtags, even your phone’s language. But how are these elements weighted? That’s a mystery. As one employee told The Guardian, “There’s no magic formula. It’s so complex that even the team that built it doesn’t fully understand why certain videos go viral.”

And here lies the real challenge: Oracle will have “technical control” of the U.S. algorithm. But what does that even mean—to control something its own creators barely understand? An algorithm built on years of data, experimentation, and millions of micro-adjustments. Touch it the wrong way, and you break the magic. Without that magic, TikTok becomes just another video app, and a $14 billion deal could turn into a very expensive mistake.

A New Twitter?

But there’s another layer to this gamble and recent events suggest the outcome is far from certain. Recently, Trump met with Xi Jinping and—just one month after the initial deal—neither leader has confirmed China’s approval of it. While Trump remained particularly silent, Beijing’s Commerce Ministry offered only carefully worded reassurance that it would “properly resolve TikTok-related issues”—the kind of diplomatic non-answer that signals reluctance, not agreement.

However, if the sale goes through without major changes to the terms, TikTok could change radically for U.S. users. Trump has openly declared he wants TikTok to go “100 percent MAGA.” And the conservative tilt of his hand-picked investors—Oracle, Silver Lake, Andreessen Horowitz—suggests this isn’t just talk.

Kelley Cotter, who studies social media algorithms at Penn State, explains the mechanics: an owner with strong ideological commitments can reshape a platform’s content ecosystem simply by adjusting algorithmic weights (Scientific American). Republican lawmakers have already voiced concerns about perceived bias in TikTok’s content moderation. Under U.S. ownership, those concerns could become policy—encoded directly into the algorithm itself.

The parallel with Twitter is impossible to ignore. When Elon Musk acquired Twitter in 2022, he promised a return to free speech principles. What followed was ideological realignment. Algorithmic changes amplified certain voices while suppressing others. Progressive users abandoned the platform en masse, migrating to Bluesky and Mastodon. What remains is an app increasingly shaped by Musk’s political priorities—a cautionary tale of how ownership transforms ecosystems.

TikTok faces the same risk. If left-leaning users perceive the platform shifting right under Trump-aligned ownership, they could leave. The content mix—currently chaotic, diverse, unpredictable—could narrow into what Cotter describes as “an app composed only by a subset of American users, particularly right-leaning ones.” The algorithm wouldn’t need to break. It would just need to bore people. Trump may secure formal control of TikTok. But the platform’s actual power—its ability to command attention, shape culture, generate revenue—could evaporate in the transition.

The Real Question

This technical gamble comes at a particularly delicate moment, and user growth is no longer guaranteed. Australia and France want to ban it for minors (BBC). Usage time is dropping in some Western markets as Instagram and YouTube push similar formats. Parents are more aware, kids are more supervised, and some even talk about the end of the social media era (Financial Times).

Trump wants a TikTok that’s American, controllable, and compliant. But is that even possible? A “domesticated” version, stripped of its Chinese secret sauce and answerable to the U.S. government, might lose exactly what made it irresistible.

Meanwhile, the U.S. may end up throwing the baby out with the bathwater. China, as it recently showed with DeepSeek, might just reinvent itself and restart the tug of war from scratch. And 170 million Americans could wake up one day to an app they no longer recognize.

Perhaps the only winner will be Xi Jinping, who, according to Trump, “blessed” the deal. Hard not to wonder: did he really lose—or just let Trump buy a broken toy?