Global Perspectives

August 2024

Key Statistics

- The 1st country in the world for proven oil reserves.

- The 4th country in Latin America to gain independence from Spain.

- The 3rd most urbanized country in Latin America.

- The 6th country in the world for natural gas reserves.

- The 9th most biodiverse country in the world.

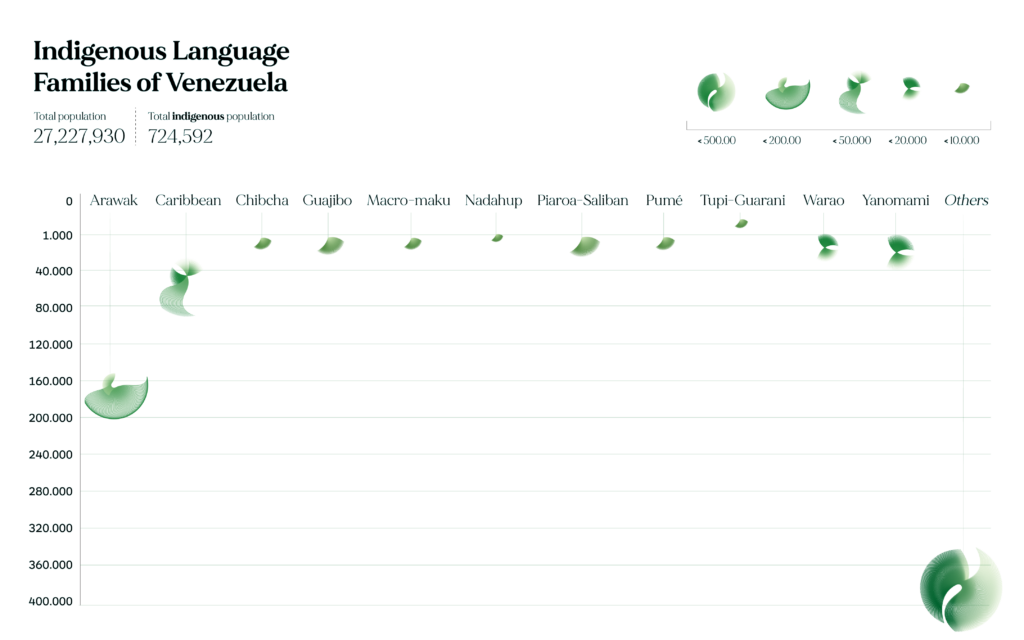

A Multilingual Constitution

Hidden among the dense forests of Venezuela, over 34 ethnic groups safeguard millennia-old cultures that resist the passage of time and modernization. They represent the vibrant diversity of the country, which is composed of mestizos comprising 65%-90% of the population and indigenous groups making up only 2.9%, a small fraction of the total population of over 28 million inhabitants (IWGIA). Among the most populous groups are the Warao, Wayuu, and Pemon, whose traditions of agriculture, hunting, fishing, and gathering are the lifeblood of their existence.

Hugo Chavez, declared president in 1998, made several efforts to empower indigenous communities. In fact, he not only proclaimed himself a indigenous leader but also promoted extensive constitutional reform. Through the 1999 Constitution, one of the world’s most progressive regarding indigenous community rights, Venezuela was defined as a multi-ethnic, pluricultural, and multilingual republic. It recognized indigenous languages as co-official and reserved three seats in the National Assembly for indigenous representatives.

Artículo 9. «El idioma oficial es el castellano. Los idiomas indígenas también son de uso oficial para los pueblos indígenas y deben ser respetados en todo el territorio de la República, por constituir patrimonio cultural de la Nación y de la humanidad.»

Despite these efforts, indigenous communities continue to live in vulnerable conditions, primarily due to the lack of demarcation of indigenous territories, illegal mining activities, and environmental degradation. For example, although the Constitution mandated that the state transfer their lands within two years, reports indicate that only a small fraction, no more than 13% of the total land, has been granted (VenezuelanAnalysis). For instance, it was only in 2009 that the government issued property titles to the Yukpa indigenous people for 41,600 hectares in Zulia State, benefiting three communities totaling 500 individuals. Nonetheless, this has not fully resolved land disputes for the larger community of 10,000 indigenous people. Furthermore, in 2017, the government initiated the Orinoco Mining Belt megaproject, encroaching upon autonomously demarcated indigenous territories to promote largely illegal extractive activities.

Venezuela

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!The Amazon Black Hole

These extractive activities are the main threat to Indigenous Peoples’ rights. This phenomenon not only caused significant environmental destruction but also impoverished and rendered the local communities vulnerable, exposing them to extremely dangerous working conditions. The high global price of gold, along with Lula’s crackdown on criminal groups in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, attracted numerous illegal gold miners to Venezuela’s forests, bringing with them alcohol, prostitution, and malaria.

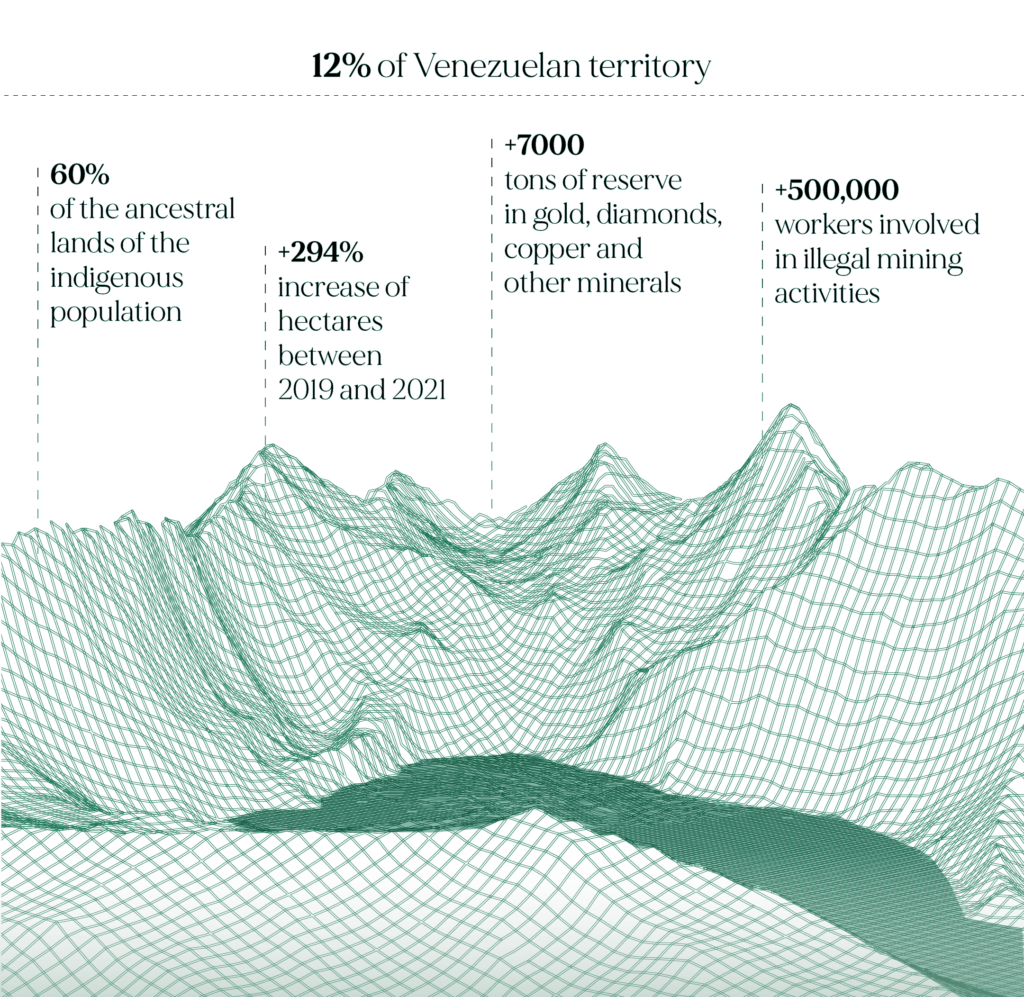

In 2011, then-President Hugo Chávez announced his intention to open a large portion of Venezuela’s southern territory to mining activities. In 2016, as Venezuela’s economy spiraled into crisis, Chávez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro, officially implemented this vision, designating 12% of the country’s territory as the Arco Minero del Orinoco: an area rich in minerals that spans approximately the size of Portugal across the Amazonas, Bolívar, and Delta Amacuro states (CSIS). This area contains bauxite, coltan, industrial diamonds, and most importantly, gold.

The Arco Minero quickly became a hub for illegal mining, where armed non-state actors and local gangs – with the support of the regime – competed for control of key mining operations. However, illegal activities extend far beyond the boundaries of the Arco Minero, extending inside the Canaima and Yapacana National Parks and several other protected areas. Approximately 500,000 workers are involved in illegal mining operations, many from local indigenous communities who have been coerced into working through threats of violence or economic necessity. These miners are mostly impoverished Venezuelans, with an estimated 45% being underage (IWGIA).

Specifically, in the states of Amazonas and Bolívar, there are plenty of people from all corners of the country, chasing the El Dorado myth. There are various types of people: criminals, youngsters from East Caracas, doctors, lawyers, teachers, former police officers, former soldiers, workers, fishermen, and accountants. Also present are women, girls, and elderly people.

In the mine located in Yapacana National Park, known locally as “La Finca,” an estimated 15,000 people live together, becoming the second-largest agglomeration in the state of Amazonas after its capital, Puerto Ayacucho.

More than others, indigenous communities are severely affected in their social, cultural, and economic structures by the actions of irregular groups and mafias that have strengthened in the area. Although migrants enter the mines hoping to change their fate and that of their loved ones, the reality is often less benign. Indigenous youth die from violence or precarious working conditions; women of all ages fall prey to forced prostitution; and people end up working in semi-slavery conditions to pay debts and inputs to the “owners” of the mines.

The mines, like a black hole, end up dragging indigenous men and women into their vortex. Some come “voluntarily,” but many others are coerced. In fact, indigenous people have few choices: they either become miners or are overrun by mafias. They have to migrate to the mining camps, affecting the daily routines of those who remain in the communities as well. Due to conflicting opinions about mining activity among community members, their governance structures are fragmenting. Moreover, the ability to resist external pressures is diminishing. All this impacts the productive capacity of indigenous peoples over their lands, territories, and resources, as well as their right to autonomy and self-government.

The mines, like a black hole, end up dragging indigenous men and women into their vortex.

An additional element to consider is the serious ecological impact that directly affects indigenous communities. Numerous reports indicate mercury poisoning from mine consumption: rivers are contaminated, and so are the fish, the main food source for the indigenous people. At the same time, outsiders bring diseases that wreak havoc on communities. The spread of malaria in recent years is also a result of mining, as deforestation and land erosion create stagnant water conditions where mosquitoes proliferate.

According to Wataniba’s estimates, based on satellite images cross-checked in the field with community members, the land area directly affected by gold mining has grown rapidly since 2016. In 2019, it reached approximately 33,900 hectares, and by 2021, about 133,700 hectares, an increase of 294% (Debates Indigenas).

Chávez: “corazón de mi patria”

Nothing is simple in Caracas. One of the most unequal countries in Latin America, Venezuela has transitioned from a situation of wild and predatory capitalism to a para-communist authoritarianism, in crisis since 2013. In 1998, Hugo Chávez, leading the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, won the election with a socialist agenda that was openly hostile to capitalism. Under his leadership, the richest country in the continent in the 1970s, due to its oil resources, entered a spiral of economic and political crisis.

While oil prices were high, Chávez financed social programs and subsidies not only for poor Venezuelans but also for neighboring countries through initiatives like Petrocaribe. He aimed to rebalance the inequality between the rich and poor, becoming a highly popular leader. Internationally, Chávez promoted “Bolivarianism,” an ideological blend of communism, sovereignty, and Third Worldism, characteristic of left-wing populism in Latin America. During his presidency, unemployment rates decreased, per capita income rose, and poverty and infant mortality rates declined. The oil boom in the 2000s allowed Chávez to maintain economic stability despite foreign capital flight. In fact, the country remained tied to its oil resources, exposing the economy to structural vulnerabilities.

After Chávez’s death, his successor Nicolás Maduro faced worsening conditions. Lack of investment in new technologies and mismanagement of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) drastically reduced oil production, and with the collapse of oil prices in 2014, Venezuela entered a severe economic crisis. Exports, mainly crude oil, saw a significant slowdown, and Maduro struggled to fund social policies like his predecessor.

Meanwhile power increasingly shifted to military forces, controlling crucial sectors like the state oil company, mining resources, and food and medicine distribution. In addition to that, the country faced a political crisis, because the legitimacy of Maduro’s reelection in 2018 was questioned. Opposition leader Juan Guaidó self-declared himself as interim president, gaining support from many Western nations, including the United States. However, his tenure ended in December 2022 when the National Assembly decided to remove him to normalize relations with Maduro’s government.

Source: Statista

Further complicating matters, Venezuela faced severe international sanctions from countries like the United States, Canada, and Panama, aimed at destabilizing the regime and pushing for governmental change. Sanctions limited Venezuela’s access to international markets, making it even harder for the government to procure essential goods and stimulate the economy.

Crypto Resilience

In this crisis, Venezuela has become an emblematic case of how cryptocurrencies can emerge as tools for economic survival and political resistance. The root causes of cryptocurrencies popularity lie in the catastrophic devaluation of the bolívar, the national currency, which has lost almost all its value amid inflation rates surpassing one million percent. Around 10% (TripleA) of the population began converting their savings into Bitcoin, Ether, and other digital currencies, using them not only as a store of value but also as a means for daily payments and international transfers, bypassing the restrictions imposed by the sanctions.

An example of cryptocurrencies usage is that during the COVID-19 crisis. The interim government, led by Juan Guaidó, used them to bypass Maduro’s regime’s restrictions and provide direct aid to doctors and nurses. This innovative program allowed funds to be transferred directly to recipients through digital wallets, avoiding the control of government banks. In a country where the average doctor’s salary was only $5 a month, this aid, amounting to $100 per month, provided vital relief for thousands of healthcare professionals. On the other hand, the spread is so extensive that in some cities, such as Caracas, Maracaibo, and Valencia, it is possible to purchase almost everything, from groceries to furniture, using digital currencies.

Furthermore, the rise of mining—the energy-intensive process of generating digital currencies—has been significant thanks to Venezuela’s abundant and cheap energy resources, a byproduct of its vast oil and gas reserves. This has not only provided a source of income but also integrated Venezuela into the global digital economy, helping alleviate some effects of its economic isolation.

In an attempt to regulate and capitalize on this phenomenon, Maduro’s government launched the Petro in 2018, a state-backed cryptocurrency pegged to the value of oil. However, the lack of transparency and trust prevented Petro from gaining significant international acceptance. In parallel, the government established the National Superintendency of Crypto Assets and Related Activities (Sunacrip) to monitor and regulate cryptocurrency-related activities, and recently, the regime has attempted to regulate and sometimes restrict cryptocurrency activities to control energy consumption and stabilize the power grid, which suffers from frequent blackouts. However, these efforts have not dampened the widespread and growing use of digital currencies among the population.

Source: Cointelegraph

Miss Universo : a Path to Economic Empowerment

Another example of Venezuelan resilience is the cosmetic surgery sector, which has continued to prosper, becoming a path to economic empowerment for many Venezuelan women. Venezuela is known for having one of the highest rates of cosmetic surgeries in the world, and ten years ago – at the right beginning of the economic crisis – it surpassed countries like South Korea and Iran. In a context where 96% of families live below the poverty line and 79% in conditions of extreme poverty, turning to plastic surgery might seem an unsustainable luxury.

However, in 2018 Venezuelans spent over 200 million dollars on plastic surgery because the culture of beauty is so deeply rooted that, according to the Venezuelan Society of Plastic Surgery (SVCP), in recent years someone had a cosmetic operation every six minutes. This phenomenon knows no social barriers: women of all classes, including the humblest, make significant sacrifices, even foregoing basic necessities to enhance their physical appearance. Yet, beauty in Venezuela is not merely an aesthetic aspiration, but it’s a tool for social and economic mobility: in a country with limited job opportunities and one of the lowest female employment rates in Latin America (36.9%), many women see beauty as an escape from poverty.

The Country With The Most Beauty Pageant Crowns

Source: Statista

Through participation in beauty pageants like Miss Venezuela and Miss Universe, winners and participants are provided with a launchpad for developing successful careers. The Miss Venezuela contest epitomizes this dynamic: participants gain skills beyond physical beauty through rigorous training, which enables many women to build successful careers as actresses, television journalists, and even politicians, such as Irene Saez, a former Miss Universe and presidential candidate. These contests, which have seen Venezuela win 13 Miss Universe and Miss World titles, are deeply ingrained in national culture and are considered events of pride and national significance.

The phenomenon of Venezuela’s beauty market represents an extraordinary case of how, in a context of extreme economic crisis, beauty can become a strategic resource for women’s survival and emancipation. In a country where physical appearance is elevated to a system, beauty becomes a powerful tool of resistance and hope.