Global Perspectives

April 2025

Commanding the gateway between Europe and Asia, crucial to energy corridors, and central to regional diplomacy, Turkey has become a nation that shapes outcomes far beyond its borders. With NATO, Russia, China, and the Middle East all vying for influence, this country is no longer just a strategic partner—it’s a power broker in its own right, indispensable in the unfolding dynamics of the 21st century with its own complex internal dynamics.

Key Statistics

- The 2nd largest army in NATO after the United States.

- The 3rd largest exporter of TV series after the U.S. and the U.K.

- The 6th most visited country in the world.

- The 4th largest textile exporter in the world.

- The world’s leading exporter of boron.

- The world’s largest host of refugees.

Lost in Silence

Straddling Europe and Asia, a nation without formal borders stretches across rugged mountains and deep valleys in four different countries, home to around 30 million people who defy conventional definitions of statehood and nationhood. Deeply rooted in indigenous traditions, they continue to wear traditional attire, while cinema, music, and literature serve as powerful tools of self-determination and cultural resistance. They are the Kurds, the world’s largest stateless nation (ISPI). In Turkey alone, more than 17 million Kurds live in southeastern Anatolia along the borders with Iran, Syria, and Iraq. While public discourse often celebrates successful stories of indigenous empowerment, it is equally crucial to examine unresolved cases where the right to self-determination remains an ongoing struggle. The Kurdish battle for recognition has spanned more than four decades, marked by armed conflict, hundreds of thousands of deaths, and acts of resilience that have echoed across global indigenous movements.

In March 2025, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) declared a unilateral ceasefire in its long-standing insurgency against the Turkish government. The announcement followed a statement by imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan, who urged militants to lay down their arms. The move sparked cautious hope and raised key questions. What brought about this moment? And what lies ahead for the Kurds in Turkey? To understand the significance of this event, we must first look back at the historical context of the Kurds’ identity and their complex relationship with the Turkish state.

Long before the birth of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, Kurds were recognized as a distinct nation within the multicultural Ottoman Empire. Following the creation of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founding father, initially acknowledged the Kurds and promised autonomy for Kurdish-majority provinces. However, as Atatürk consolidated power, his vision for a homogeneous nation-state—one people, one language, one nation—took precedence. This vision led to the suppression of Kurdish identity and culture. Kurds were encouraged to assimilate into the Turkish identity, with the Kurdish language banned and Kurdish people often referred to as “mountain Turks,” denying them their unique cultural and linguistic heritage. Policies of forced assimilation sought to erase the Kurdish presence from the national consciousness, outlawing forms of cultural expression such as music and literature.

Tensions escalated during the 1920s and 1930s, resulting in uprisings led by Kurdish leaders like Sheikh Said and Seyit Riza, who demanded cultural and linguistic rights. These rebellions were violently suppressed, leading to tens of thousands of deaths and exacerbating the divide between the Kurdish population and the Turkish government. At the core of the issue was—and still is—language: Kurdish, spoken in its main dialects of Kurmanji and Zazaki, became not just a tool for communication but a vital symbol of ethnic identity. A 2015 study revealed that, for over 70% of Kurds, language is a central factor in their ethnic identity (Gdańsk University Institute of Archeology and Ethnology), while a 2019 survey further showed that 71.5% of Kurds believed Kurdish should be an official language alongside Turkish (Rudaw, 2019). This is unsurprising, as language has become the glue that binds the Kurdish people, who are dispersed across different countries and facing cultural marginalization.

Despite the central role of language in Kurdish identity, Turkish policies have consistently sought to limit its use. After the military coup in 1980, speaking, publishing, or singing in Kurdish became illegal, leading to arrests and imprisonment for those who defied the ban. Even personal names with letters from the Kurdish alphabet, such as “q,” “w,” and “x,” were prohibited. In the 2000s, there were some small steps toward linguistic openness, such as the introduction of Kurdish as an optional subject in schools, but participation remained minimal.

A 2020 survey highlighted the ongoing effects of these policies: although 80% of Kurdish parents with children aged 3 to 13 claimed to speak Kurdish, only 24% used it as the primary language at home. Among urban youth aged 18 to 30, fewer than half regularly use Kurdish, and just 18% are literate in their native tongue (Kurdish Studies Archive, 2025). These statistics underscore the profound impact of forced assimilation on the transmission of the Kurdish language across generations.

A 2015 study revealed that, for over 70% of Kurds, language is a central factor in their ethnic identity, while a 2019 survey further showed that 71.5% of Kurds believed Kurdish should be an official language alongside Turkish.

In response to these efforts to erase their language and culture, the PKK was founded in 1978 by Abdullah Öcalan. Initially seeking an independent Kurdistan, the PKK’s demands later evolved toward greater autonomy and cultural rights within the existing state structures. Since 1984, the PKK has waged an armed struggle against Turkey, resulting in nearly 40,000 deaths and the displacement of millions of civilians. Considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union, the PKK is viewed by many Kurds as a symbol of resistance.

The Kurdish struggle, however, is not only a battle against political and cultural repression; it is also a fight for recognition and inclusion. The ceasefire announced in 2025 represents a potential turning point in this ongoing conflict. The demands of the Kurds are clear: official recognition of the Kurdish language, the right to education in their mother tongue, and political participation. These are essential steps toward genuine inclusion and respect for the Kurdish people. Turkey now faces a critical choice: continue with the marginalization of Kurds or embrace its internal diversity, recognizing that national unity need not rely on cultural homogeneity.

Source: Research Gate

Ninety Days of Linguistic Revolution

Kurdish is now the second most spoken language in Turkey despite decades of marginalization. But it isn’t alone. More than 30 ethnic languages still survive across the country, though most remain invisible in public life. Their erasure is no accident: it’s tied to a deliberate process, one that began a century ago with the creation of a national language. Modern Turkish as we know it today is less than a hundred years old. And it was introduced in just three months. Ninety days to rewrite the linguistic identity of an entire nation.

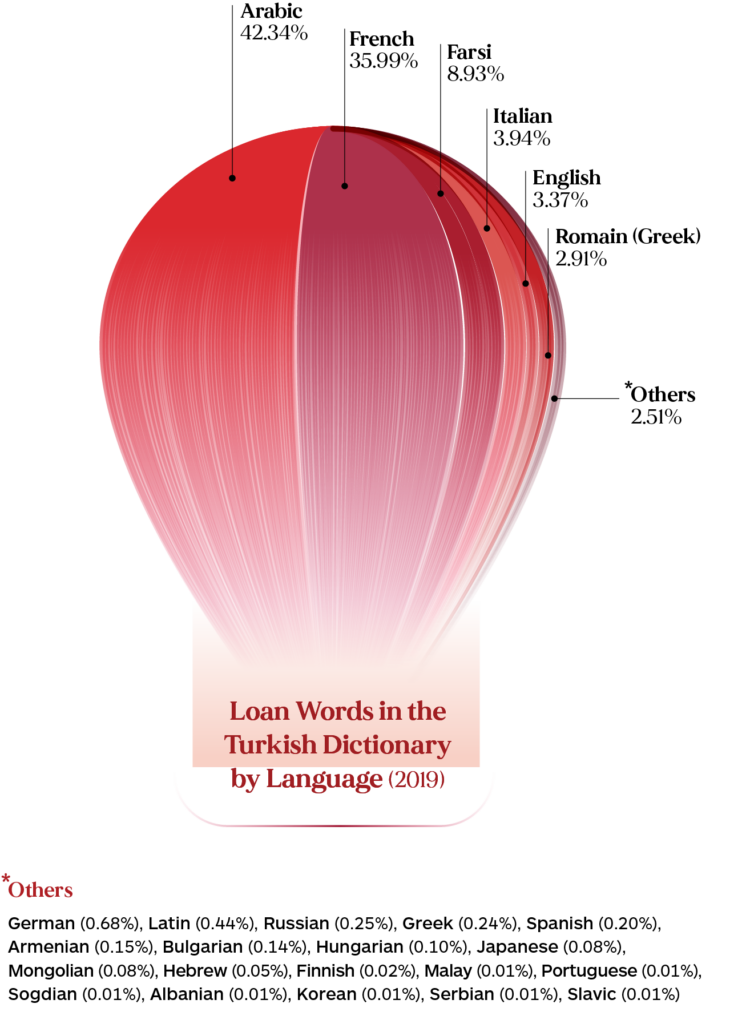

When the Republic of Turkey was born in 1923, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk launched a bold project of modernization and Westernization. At the heart of it was language. For Atatürk, words were more than a means of communication—they were tools for shaping a new national spirit. Up until then, the official language had been Ottoman: a complex blend of Turkish, Arabic, and Persian, written in Arabic script and accessible only to a narrow elite. Just 10 percent of the population was literate, with even lower rates among the Muslim majority (New Lines Magazine). The linguistic reform would be the first chisel blow in the construction of the new Turkey.

Turkey

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Discover it here!In 1928, the break came. Atatürk ordered the replacement of the Arabic alphabet with a Latin one tailored to Turkish phonetics and made up of 29 letters. Gone were “q,” “w,” and “x”; in came characters like “ç,” “ğ,” “ı,” “ö,” “ş,” and “ü.” The shift was swift and uncompromising. Although the Language Council had suggested a gradual transition, Atatürk insisted: “Either in three months, or never.” On November 1, the reform passed in Parliament. Overnight, a revolution was underway—not just in how people wrote, but in how they thought.

But the transformation ran deeper than the alphabet. In 1932, the Türk Dil Kurumu (Turkish Language Association) was founded with a clear mission: to “purify” the language by removing foreign elements. Arabic and Persian words were replaced with newly coined Turkish alternatives. İlim became bilim (science), hürriyet turned into özgürlük (freedom), istikbal gave way to gelecek (future). The aim was to bring the written language closer to everyday speech and, in doing so, forge a shared, modern identity.

Few linguistic reforms are as emblematic as Turkey’s: deliberate, top-down, and transformative, it is a unique example of how a language can be deliberately engineered with a political act intended to sever ties with the Ottoman past and propel Turkey toward the West. For this purpose, translators played a fundamental role. With the new vocabulary and Latin alphabet, millions of texts had to be transliterated and adapted. In the 1940s, the Tercüme Bürosu (the Translation Bureau) was created, bringing great Western literature to Turkey. Translating was not just a linguistic exercise but a means to introduce new concepts and spread a more cosmopolitan culture, fostering critical thinking and opening windows to the world.

İlim became bilim (science), hürriyet turned into özgürlük (freedom), istikbal gave way to gelecek (future).

The results were measurable. Literacy rose from 10.6% in 1927 to 22.4% by 1940, while today it sits at 97.6% (Macrotrends, 2025). The Millet Mektepleri—National Schools—taught both children and adults to read and write in the new script. Yet the cost of reform was steep. Older generations suddenly found themselves cut off from their cultural memory. Literature, religious texts, and historical documents were locked behind an abandoned writing system, now accessible only to scholars.

In the decades that followed, the effort to cleanse the language intensified. The result was often an awkward, artificial prose disconnected from the living language. Eventually, pragmatism softened the purist zeal. Foreign words that had taken root in daily life were quietly allowed back in. Today, walking through Istanbul, you’ll hear otobüs (bus), telefon (telephone), and taksi (taxi). Despite decades of control, the language resisted constraints. It absorbed, adapted, and evolved. Modern Turkish remains a mosaic layered with traces of past empires, cultural exchanges, and global influences. In the 19th century, French was the language of progress; today, English dominates, especially in technology and pop culture.

Source: Research Gate

Yet the question of language is far from settled. In recent years, under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (AKP), a new linguistic shift has taken shape. Ottoman vocabulary and Islamic references are making a comeback. Religious schools and programs have expanded, aiming to cultivate a generation grounded in tradition. But the push has sparked resistance. Many young people feel alienated. Surveys suggest that over half would leave the country if they could, disillusioned by growing cultural restrictions and political conservatism.

At the same time, technology is helping to reconnect the present with the past. Projects like AKİS—the Ottoman Transcription Tool, developed with support from Turkey’s Scientific and Technological Research Council—use artificial intelligence to transliterate Ottoman texts into modern Turkish. These tools are helping restore access to the nation’s collective memory, closing a gap left by the 1928 reform.

Still, we can’t forget where it all began. Declaring Turkish the sole official language was central to Atatürk’s vision: a unified nation free from ethnic and linguistic divisions. That decision shaped modern Turkey—not just culturally, but geopolitically. The reform accelerated the turn toward the West, expanded literacy, and laid the groundwork for a national identity that could bridge tradition and modernity. Today, Turkey continues to straddle continents, presenting itself as both European and Middle Eastern, modern and rooted, progressive and historical. At the heart of this balancing act lies the question of language. It remains a marker of identity, a tool of power, and a mirror of change.

The Tug of War: Turkey’s Soft and Hard Power

Laiklik and Turkey’s Rise on the World Stage

On July 24, 2020, millions of worshippers gathered outside Hagia Sophia in Istanbul for the first Islamic prayer held there in 86 years. The reconversion of the monument—originally turned into a museum by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk—was not merely a religious act but a powerful political statement. With this move, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan dismantled one of the most iconic symbols of Turkish secularism (laiklik), one of the founding pillars of the Republic now increasingly under strain.

The principle of laiklik, enshrined in the 1937 Constitution, was never modeled after French-style secularism. In Turkey, religion has never been excluded from the public sphere; instead, it is managed. The very existence of the Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı—the Directorate of Religious Affairs—attests to this. Created in 1924, just a year after the Republic itself, the Diyanet now employs more than 130,000 people and commands a budget larger than several major ministries (BirGün, 2024), including the Ministry of the Interior. It oversees over 90,000 mosques, issues official religious guidance, trains and assigns imams, and funds Islamic education both at home and abroad. Far from separating mosque and state, the Diyanet institutionalized their relationship, operating as the ideological arm of the government in matters of Sunni Islam.

But managing belief is not the same as neutralizing it. Over time, this arrangement has generated friction and even deep fault lines. Between 1960 and 1997, Turkey experienced five military coups, each one justified as a necessary defense of Kemalist values. These interventions reveal how the state has long perceived religion as a potential threat to the secular order. And yet, despite the state’s controlling gaze, religious sentiment has remained deeply rooted. According to data from the think tank KONDA, more than 88% of the population identifies as Muslim, and roughly half report praying regularly. Since rising to power in 2002, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has capitalized on this enduring religiosity by dismantling secular barriers, reasserting Islamic references in the public sphere, and presenting religion as both heritage and a political mandate.

Even so, laiklik continues to serve as a vital strategic asset for Ankara. It is precisely this principle that has allowed Turkey to position itself, for decades, as an outlier in the Muslim world: a nation with a Muslim-majority population, yet governed by secular institutions, democratic norms (however contested), and a historically Western orientation. This image was crucial in securing Turkey’s NATO membership in 1952, and later, its candidacy for European Union accession in 1999. For much of the 20th century, secularism served as a kind of geopolitical passport—an assurance to the West that Turkey was a reliable partner, straddling civilizations without losing balance. A bridge, not a frontier.

Geography has only reinforced that metaphor. Positioned between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, Turkey has crafted a unique voice, fluent in the language of Brussels and Cairo, Washington and Tehran. Secularism has given it credibility in global diplomacy while preserving access to Muslim-majority contexts. Today, Turkey ranks third in the world in terms of diplomatic presence, with 252 embassies and consulates across the globe (Global Diplomacy Index, 2024). Laiklik, therefore, is more than just a domestic issue. It is a geopolitical tool.

Research Report 2025 is rolling out!

A journey through localization, technology, language, and research.

The ultimate resource for understanding AI's impact on human interaction. Written by a global community of multidisciplinary experts. Designed to help navigate the innovation leap driven by automatic, affordable, and reliable translation technology.

Secure your copy nowHard Power: Economy, Military Strength, and Energy

Turkey has always been a crossroads—a physical and symbolic bridge between continents, cultures, and geopolitical interests. But in recent years, the country has changed its guise. No longer content to simply mediate between East and West, Turkey now presents itself as a protagonist. It does so with a clear ambition, backed by a combination of economic, military, and strategic levers that have allowed it to claim a more confident seat at the tables that matter. No longer just a middle ground, Turkey is aiming to become the center.

The engine of this transformation has been primarily economic. Despite domestic upheaval and a currency that has weathered storm after storm, Turkey has kept its growth trajectory largely intact. In 2023, its GDP reached $1.024 trillion, securing its place as the world’s 17th-largest economy (World Bank, 2024). This achievement—in the face of global slowdowns and local uncertainty—speaks to Turkey’s ability to marry traditional sectors with cutting-edge industries, while deftly balancing its economic ties between East and West.

Agriculture remains a foundational pillar, employing nearly 14.6% of the workforce (Trading Economics, 2023). The country leads the world in hazelnut—accounting for more than 70% of the global supply—and tea production, with exports that anchor rural livelihoods and bolster global supply chains. Yet alongside the fields, factory floors are buzzing. In 2023, the country produced nearly 1.47 million motor vehicles (Statista, 2023), a figure that dipped only slightly in 2024. Companies like Tofaş and Oyak-Renault, Vestel and Arçelik are exporting appliances and technology worldwide, signaling the country’s shift from traditional manufacturing to an advanced industrial hub.

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute

This industrial strength has paved the way for a parallel expansion of military capacity. With NATO’s second-largest army and a defense budget of $9.6 billion in 2023 (Al Jazeera, 2025), Turkey has invested systematically in its own defense sector. The goal is clear: technological self-sufficiency and reduced dependence on foreign suppliers. The strategy is paying off. Turkish arms now represent 1.7% of global defense exports, placing the country 11th worldwide between 2020 and 2024, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI, 2025). The crown jewel of this drive is Baykar Technologies and its Bayraktar TB2 drone—a game-changer in modern warfare and a powerful symbol of Turkish innovation. Used in over 30 countries, these drones have reshaped battlegrounds and burnished Turkey’s military reputation. In 2024 alone, defense and aerospace exports reached $7.1 billion (Defense News, 2025). But Ankara exports more than drones—it exports alliances, expertise, and a sense of presence.

Its strategic position has long worked in Turkey’s favor, but in today’s climate, its importance has only grown. Control over the Bosporus and Dardanelles—vital maritime corridors linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean—has become even more critical since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the reshuffling of global energy routes. Over 80,000 commercial vessels pass through these straits annually, many carrying energy destined for Europe (Statista, 2024). An estimated 3% of the world’s oil flows through these narrow waterways (World Economic Forum), underscoring Turkey’s pivotal role in global logistics and energy security.

Infrastructure projects have only bolstered this influence. TurkStream, operational since 2020, channels 31.5 billion cubic meters of Russian gas to Europe via Turkey. The Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) adds another 16.2 billion cubic meters, bringing Azeri gas westward. Through these pipelines, Turkey has entrenched itself as both a supplier and a broker, indispensable to Europe’s energy strategy.

But it’s not just about transit—Turkey also wants to produce. The discovery of the Sakarya gas field, one of the largest offshore reserves in the Black Sea, could significantly reduce the country’s energy dependency, which still hovers at around 74%. The government plans to cover up to one-third of domestic demand with locally extracted gas by 2027 (Daily Sabah). Meanwhile, renewables are gaining ground, now accounting for 47.8% of national electricity production, led by wind and solar (Türkiye Today, 2025).

This trajectory is rooted in deliberate historical choices. Since joining NATO in 1952, Turkey has steadily shifted its international posture from an allied but subordinate state to a more autonomous and often assertive partner. Today, with a population of over 86 million (Worldometers, 2025)—largely young and urbanized—and a new national vision encapsulated in the “Türkiye Yüzyılı” (“Century of Turkey”) project launched after the Republic’s 100-year anniversary, Ankara is rewriting its role.

Challenges remain. Inflation bites. Regional tensions simmer. Relations with Western allies are often strained, and the burden of managing migration flows adds pressure to an already complex domestic agenda. Yet despite these headwinds, Turkey’s trajectory is unmistakable. Its power is no longer rooted solely in geography, but in its ability to convert vision into influence, strategy into stature. From crossroads to center stage, Turkey is no longer content to connect others—it is defining its own place in the global order.

Soft Power: From Global Diplomacy to Dizi

There is a kind of power that cannot be seen but can be felt. It seeps into tastes, languages, desires. It has no armies, yet it conquers territories. This is soft power—and Turkey has learned to wield it with precision. In recent years, Ankara has crafted a sophisticated strategy that weaves together military presence, agile diplomacy, cultural magnetism, and technological innovation. The result is a bold attempt to rewrite the rules of influence: a demonstration that a non-Western country can sit at the center of global economic and symbolic networks—without waiting for permission.

At the core of this approach is a delicate balancing act: speaking to all sides without becoming tethered to any. This tactical equidistance has allowed Turkey to emerge as a credible mediator in some of the world’s most volatile arenas. During the war in Ukraine, it offered Istanbul as a venue for negotiations, trying to maintain contact with Moscow without severing ties with the West. In Syria, it adopted a dual stance: military intervention to contain Kurdish militias, while also engaging in multilateral diplomatic processes, such as hosting over 3.1 million refugees (European Commission, 2024). Beyond reinforcing the government’s humanitarian narrative, this move increased Turkey’s centrality in its relations with Europe and the United Nations.

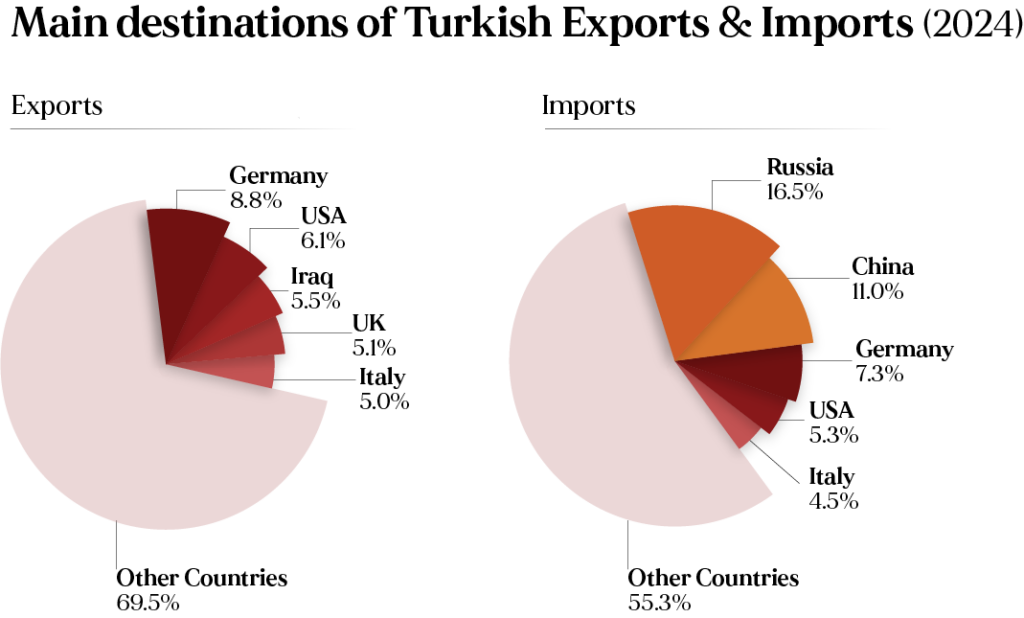

Furthermore, as a longtime NATO member, Ankara has remained central to the alliance despite tensions. Its relationship with the European Union may be fraught, but it is still vital: more than 40% of Turkish exports are bound for Europe (Statista, 2023). This economic interdependence gives Turkey enduring weight in European policy debates, especially around energy and migration.

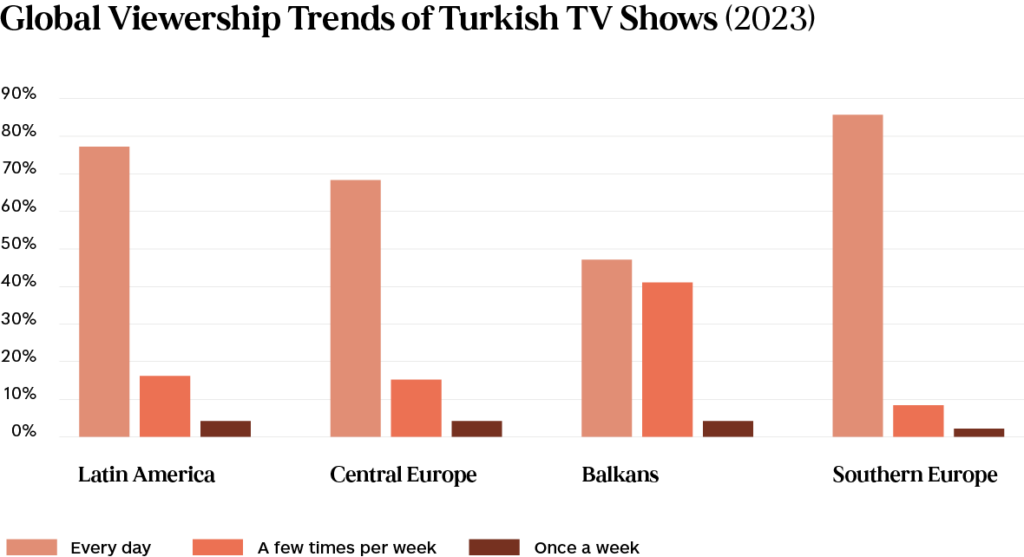

But Turkish soft power extends beyond traditional diplomacy. Ankara has amplified its presence in Africa, Central Asia, and the Balkans through embassies, infrastructure projects, and educational programs. Through agencies like TİKA and cultural institutes like Yunus Emre, Turkey has built a model of South-South cooperation, positioning itself as an alternative to traditional Western players. In the Gulf countries, Turkey has overcome past tensions and revitalized its ties with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, attracting $15.8 billion in investment as of 2022, which accounts for 7.1% of all FDI in Turkey since 2020 (Atlantic Council, 2023). Turkey is positioning itself as an actor able to step into the voids left by others, offering solutions, visions, and stories.Among these stories, more and more often, are those told through television series. Turkish dizi, now exported to over 170 countries and watched by more than 800 million viewers, have transformed global perceptions of the nation (Anadolu Agency, 2024). They are not merely cultural products, but a true form of narrative diplomacy. Drama, romance, national epics—all crafted to captivate broad audiences, from Latin America to Central Asia. This success is inevitably economic as well: TV series export revenues grew from $10 million in 2008 to over $600 million in 2023 (Istanbul Chamber of Commerce, 2024).

Source: Research Gate

But the impact isn’t just economic—it’s cultural and political. These shows project Turkish values, aesthetics, and history, contributing to a soft, resonant nationalism that travels well, strengthening Turkey’s international image. Their success has even translated into tourism: captivated by the landscapes and lifestyles portrayed on screen, millions of fans choose to visit the real Turkey. In 2022, the country welcomed over 45 million tourists—a 21% increase from the previous year—with cultural tourism playing a significant role (Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye – Investment Office, 2024).

In the 21st century, soft power is also increasingly forged in the realm of innovation. And here too, Turkey is accelerating. Istanbul has emerged as a vibrant tech hub, often dubbed the “Silicon Valley of the Bosporus.” The country has attracted over $5 billion in tech investment between 2020 and 2025 (Anadolu Agency). Despite global financial headwinds, Turkish startups raised $722 million in 2024 across more than 325 deals. Unicorns like Getir—valued at over $12 billion—and Insider, a global marketing tech company, have brought international attention to Turkey’s digital ecosystem.

The government has supported innovation with over 80 technoparks, tax incentives, and public funding for research. In 2023, R&D spending surpassed 1.4% of GDP, with a target of reaching 1.8% by 2026 (Daily Sabah, 2023). Backing this is a growing venture capital community: over 270 active funds in the country, with an increasing focus on early-stage startups. Furthermore, the ecosystem’s success is powered by a young population—nearly half under the age of 32—highly educated and rich in engineering talent: there are more than 100,000 STEM graduates each year.

This is a generation raised on Ottoman epics and mobile apps, toggling between primetime dramas and pitch decks. They move with ease between legacy and innovation—one foot in the past, the other racing toward what’s next. And in that space, Turkey is finding its edge. Here, soft power isn’t a side note to hard power—it’s the strategy. A way to shape perceptions, open up markets, and win minds without firing a shot. Influence through culture, code, and connection. Presence without pressure. Diplomacy by way of drama, design, and disruption.

And this is Turkey’s boldest move: betting that the future of power isn’t imitation, but invention. That true centrality doesn’t follow old maps—it draws new ones.