Global Perspectives

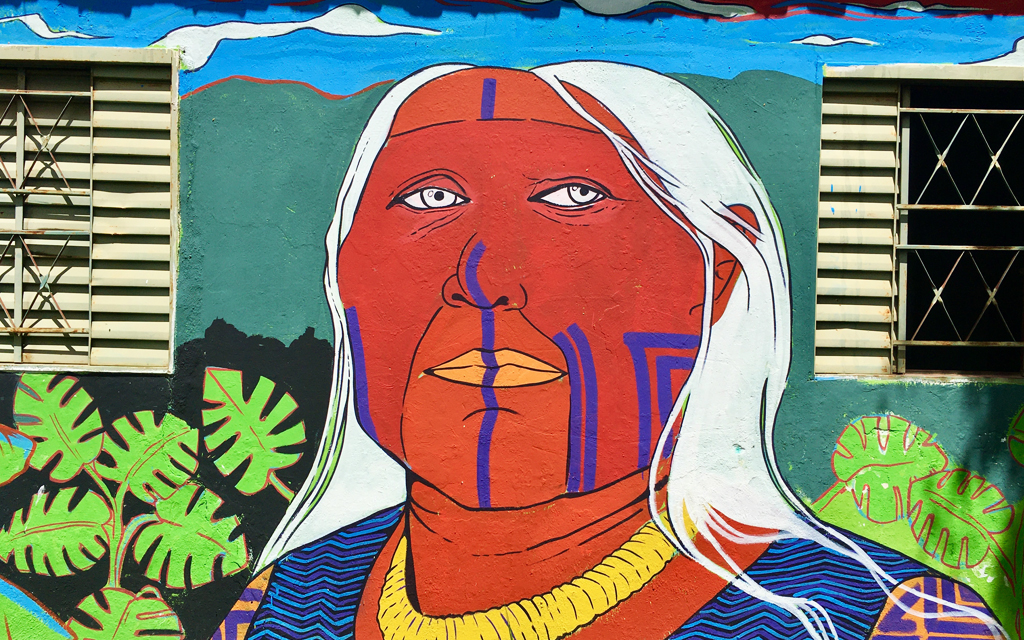

The disappearance of diversity did not begin yesterday. Over the centuries, the imposition of Portuguese and the Amazon deforestation have led to the loss of an enormous naturalistic, linguistic, cultural and human heritage. Imminent contributor since its birth, staff writer Emma Gamba has a degree in Politics, Philosophy and Economics and a master’s degree in Marketing, Analytics and Metrics.

Legend

-

1- Arawá

-

2- Arikèm

-

3- Aruák

-

4- Borôro

-

5- Chiquito

-

6- Guaikuru

-

7- Guató

-

8- Iranxe

-

9- Jê

-

10- Juruna

-

11- Karajá

-

12- Karib

-

13- Katukina

-

14- Krenák

-

15- Makú

-

16- Mawé

-

17- Maxakali

-

18- Mondé

-

19- Mundurukú

-

20- Mura

-

21- Nambikwara

-

22- Ofayé

-

23- Puroborá

-

24- Ramarama

-

25- Rikbaktsá

-

26- Tikúna

-

27- Tukano

-

28- Tupari

-

29- Tupi-Guarani

-

30- Txapakúra

-

31- Yanomami

-

32- Yatê

-

33- Aikaná e Koazá

-

34- Aikaná e Nambikwára

-

35- Arúak e Jê

-

36- Arúak e Pano

-

37- Arúak e Tupi-Guarani

-

38- Jê e Krenák

-

39 Jê e Tupi-Guarani

-

40- Kanoê e Tupari

-

41- Katukina e Pano

-

42- Arúak, Crioulo, Francês e Karib

-

43- Arúak, Makú, Tukano, Tupi-Guarani

-

44- Aikaná, Jabuti, Kanoê, Mondé e Tupari

-

45- Arúak, Aweti, Jê, Jurana, Karib, Tupi-Gurani e Trumái

-

46- Portuguese

It is estimated that when the Portuguese arrived in Brazil in 1500, around 1078 languages were spoken in the country. Due to language-related policy, most of these languages have disappeared or are disappearing. The 2010 census recorded 305 indigenous groups who speak 274 different languages. Of the indigenous people aged 5 or over (786,674 people), 37.4% speak an indigenous language and 76.9% speak Portuguese. The indigenous-speaking population is mainly found in the northern region of Brazil.

The disappearance of infodiversity did not begin yesterday. Over the centuries, the imposition of Portuguese has led to the loss of an enormous linguistic, cultural and human heritage.

1758 → the “Diretório dos Índios”, in which the Marquis of Pombal forced the use of Portuguese in the colony and prohibited the teaching of indigenous languages (in particular the “língua geral”, based on the indigenous tupi language which predominated in Brazil until the 18th century). The languages spoken by various groups of immigrants who arrived in Brazil from 1850 were also the target of these repressive actions.

1937-1945 → Getúlio Vargas’ “Estado Novo” represented the pinnacle of repression against the use of other foreign languages through the nationalisation of education which culminated in the repression of German and Italian. The Brazilian census of 1940 showed that more than one million people spoke German (644,458) or Italian (458,054) in a national population of only 50 million people – a fairly significant number. The nationalisation policy of the “Estado Novo” established the compulsory teaching of the Portuguese language in schools and prohibited the use of other languages, through a concept of “idiomatic crime”, invented by the “Estado Novo”. As a result, many people who spoke languages other than Portuguese were arrested.

In 1942, 1.5% of the population of the southern city of Blumenau, inhabited mainly by German immigrants, was marginalised due to their use of German. Finally, with the Constitution of 1988, the Brazilian state has chosen to make Portuguese the official language, although the Índios have had the right to their own language recognised also in schools. This did not happen for the other languages spoken by the descendants of immigrants. The Brazilian government has always chosen to legitimise Portuguese as the only national language.Obviously, the Portuguese language in Brazil was not imposed only by state policies. This language was adopted by a part of the colonial population, because it was considered as the one that could facilitate social contact, particularly in relation to the population segment of African origin. Portuguese colonists and their descendants never exceeded 30% of the Brazilian population and non-white ethnic groups (blacks, mulattos, Creoles and indigenous people) always fluctuated around 70% of the population until the mid-19th century. Therefore, most of the Brazilian population acquired Portuguese through the practical use of the language, although they came from families of different languages. The Brazilian people absorbed a different Portuguese, quite distant from the “official” one. In the 19th century, only 0.5% of the population was literate. In 1872, 99.9% of slaves, 80% of free men and 86% of women were illiterate. Portuguese developed in Brazil via oral use due to the absence of normal practice acquisition in schools.

Indigenous people and languages in Latin America

| Country | Indigenous people | Indigenous languages | Legal status of indigenous languages |

| Argentina | 30 | 15 | Languages of education |

| Belize | 4 | 4 | No recognition |

| Bolivia | 114 | 33 | Co-official with Spanish |

| Brazil | 241 | 186 | Languages of education |

| Chile | 9 | 6 | Languages of education |

| Colombia | 83 | 65 | Co-official with Spanish |

| Costa Rica | 8 | 7 | Languages to be preserved |

| Ecuador | 32 | 13 | Of official regional use |

| El Salvador | 3 | 1 | No recognition |

| French Guiana | 6 | 6 | Languages of education |

| Guatemala | 24 | 24 | National languages |

| Guyana | 9 | 9 | Languages of education |

| Honduras | 7 | 6 | Languages of education |

| Mexico | 67 | 67 | Co-official with Spanish |

| Nicaragua | 9 | 6 | Of official regional use |

| Panama | 7 | 7 | Languages of education |

| Paraguay | 20 | 20 | Guarani as co-official |

| Perù | 52 | 47 | Of official regional use |

| Suriname | 5 | 5 | No recognition |

| Uruguay | 0 | 0 | No recognition |

| Venezuela | 50 | 37 | Co-official with Spanish |

| Latin America | 780 | 560 |

Today, indigenous peoples are under threat more than ever.

Currently, 19% of indigenous territories are located in areas being used for legal and illegal mining; 94% of this area (381,857 km2 ) is inside officially recognised indigenous territories with 6% (25,437 km2) in indigenous lands with no legal recognition. In other words, land titles alone seem to provide indigenous people with little protection against these practices unless they are accompanied by other government action.

Today, indigenous peoples are under threat more than ever. On one hand, neo-extractivism applies strong pressure from large economic interests that direct their greed on oil, gas, gold, agro-industrial monocultures. On the other, policies that promote the “conservation” of nature without taking into account the human being. This equates to a form of ideological environmentalism that ends up considering man as cancer of the planet.

In this scenario, the conservation of indigenous languages, not surprisingly more widespread in the Amazon forest area, becomes a symbol of biodiversity and a means of safeguarding not only identities and cultures, but the earth’s green lung, the Amazon forest.

The deforestation of the Amazon rainforest took place simultaneously, albeit not in proportion, with the imposition of the Portuguese language.

Amazon Deforestation

Source: Ecoalfabeta

Amazon, the Covid-19 does not stop the deforestation. La Repubblica.

Languages spoken in Brasil. Wikipedia.

Photo credits: Thandy Yung, Unsplash / Ckturistando, Unsplash / Giulia May, Unsplash