Trends

The population of the 21st century will be called upon to choose between enduring change or guiding humanity towards its future. What will today’s young people – destined to grow up during the 21st century – do? An eye-opening question from Luca de Biase, Imminent’s Research Director.

The evolution of young humans

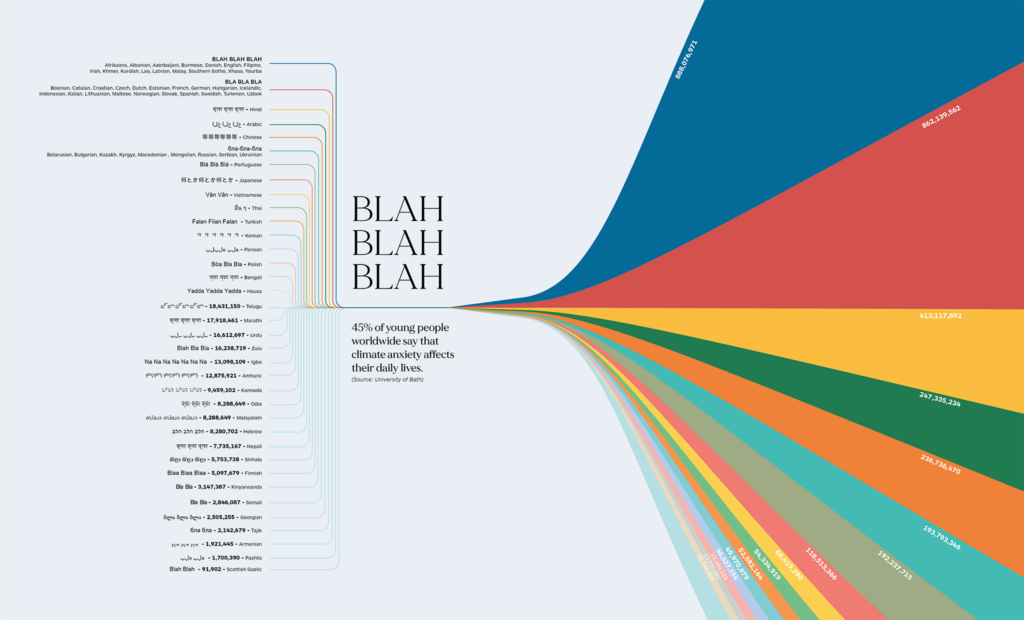

Faced with an uncertain future, young people are asking adults to act in a trustworthy manner. And that is not always achieved. In Milan, at the event organized by Youth4Climate in preparation for Cop26 on 28 September 2021, Greta Thunberg accused the world’s leaders of failing to engage beyond a hollow “blah, blah, blah”. On the other hand, they are capable of taking very firm action against youth organizations. Near the Lekki turnpike tollgate in Lagos in October 2020, Nigerian police killed at least 12 young people who were protesting against arbitrary police violence. Shots were fired at point-blank range, according to Amnesty International. In Turin, on 28 January 2022, a few hundred young people protested against the death of Lorenzo Parelli, an 18-year-old who was crushed by a girder while on a vocational training course as part of the school/work experience program: the police used their truncheons, causing twenty people to be hospitalized. In February 2022, PBS documented the protests of young women who want to go back to school in an Afghanistan that is once again under the control of the Taliban. Their demonstrations are extremely risky and are possible mainly thanks to the presence of cameras and other tools to send information to the rest of the world.

Hundreds of thousands of young people have marched for climate change to protest against governments that are not reacting and taking the appropriate measures. At COP26, despite governments reaching a global climate agreement, many were left disappointed with the outcome. Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg said that the COP26 talks had achieved nothing but “blah, blah, blah.” And that’s how these words became iconic.

Methodology: The colorful width of each language’s flow follows the volume of internet users for that language. The data source for internet users is the T-Index, which takes the ITU data on internet users and calculates the internet users per language. The assumption made is the same one as for the T-Index study, namely that people browse the internet in their native language when it is available online.

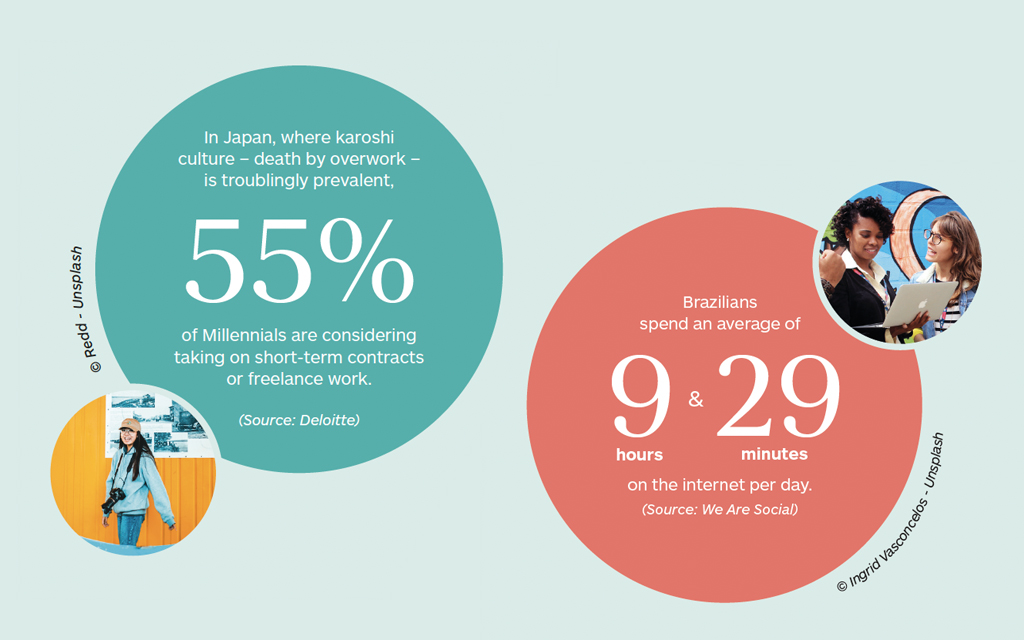

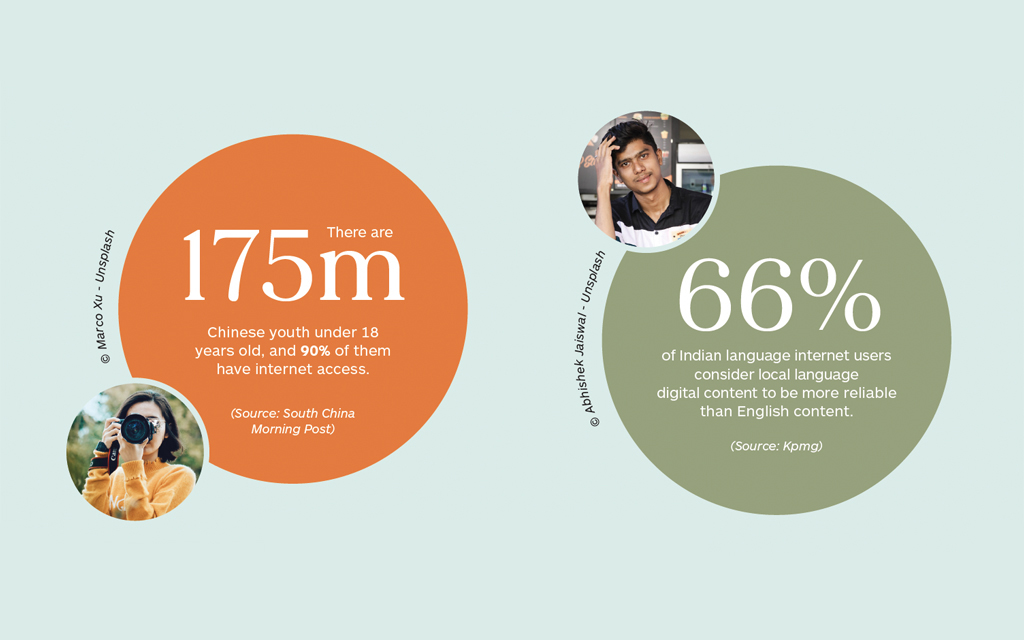

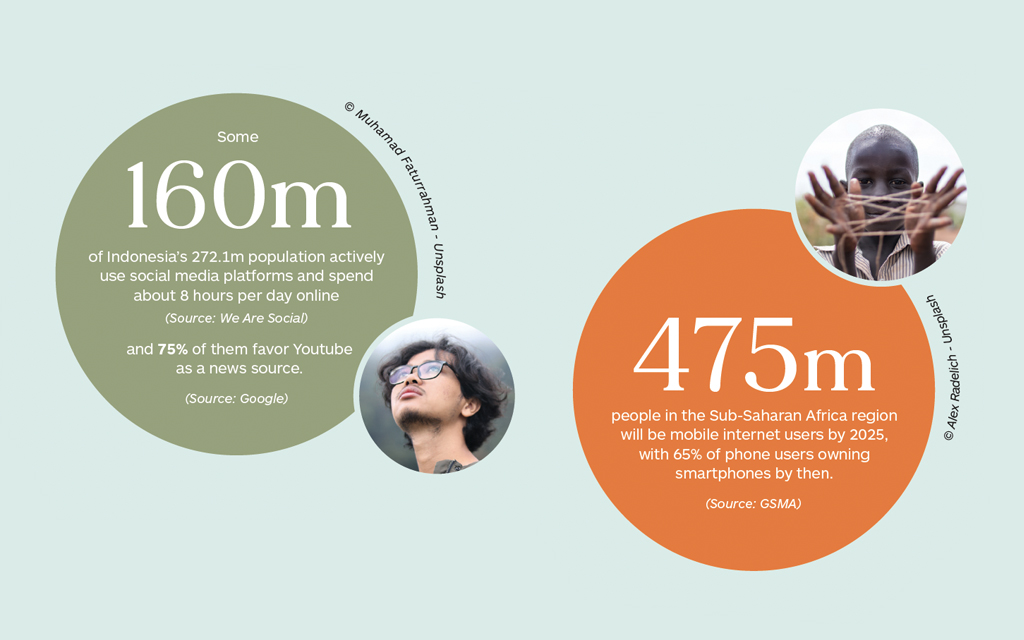

These are just the episodes of a manifest general trend. Generational distances are emerging in many contexts. In Indonesia, where the internet-connected population spends about 8 hours a day on social media, young people have designated YouTube as their community platform, and at least 27 million of them produce and post videos to accelerate a number of prominent trends: 93% of young Indonesians have recovered Islamic values as their path to happiness. At the same time, many of them set up fake profiles on Instagram to explore nontraditional social behaviors, and 52% believe that the examples set by religious leaders should not be followed, while they like celebrity influencers with tens of millions of followers who encourage traditional family behavior. From Poland to Saudi Arabia, from Ireland to Nigeria, from South Korea to Iceland, young people identify with the digital dimension as a space in which to express their critical points of view, push for change and explore new possibilities. Society has always needed their innovative drive. And today, more than ever, young people express this endeavor through new idioms, making themselves understood also beyond their specific linguistic enclaves. The world must listen to them with urgency. And attribute to them their rightful responsibility.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowA forward-looking perspective on the 21st century sees the earth’s environment undergoing profound change: with rising temperatures, increasing likelihood of extreme weather phenomena, the possible advance of deserts and melting glaciers, declining biodiversity and shrinking coral reefs. Studies by the IPCC leave little room for doubt. Although the intensity of these phenomena may be more or less severe depending on the human capacity to contain them, all of this will nevertheless occur to some extent and with major consequences: human migrations of epochal proportions, unprecedented demographic, social and economic disruption, and, at the same time, astonishing technological change driven by the growth of digital and artificial intelligence which, in turn, will accelerate genetics, neuroscience and nanotechnology. The production of energy, food, culture and all other resources essential to human life will be changed. Humans will have to talk to each other in a new way, thinking and acting differently.

This is a scenario that humans – those capable of not dismissing it – try to imagine by resorting to diverse narratives: some believe in progress that will fix everything, others foresee conflict between peoples and social classes that will wreak havoc. Several observers, focusing on the depth of the transformations underway, are mainly focused on predictable ‘revolutions’ that have started. But perhaps they are resorting to terms that are becoming too restrictive to explain the complexity of what is happening: it is no longer enough to simply study what is changing; we must relate it to what will endure. And a better notion than ‘revolution’ does indeed exist: it helps to piece together mutations and the very long term, it seeks out emerging rules in a complex reality without imposing them as models applicable to the vastness of what is possible, it points to a fundamental change that comprises all continuities and transformations. In short, instead of dissipating our focus on myriad ‘revolutions’, it is probably time to concentrate on the one and only ‘evolution’.

Evolution of the word

Language is one of humanity’s specific evolutionary characteristics. Environmental, genetic and cultural changes together constitute the dimensions of human evolution. And certainly, the complexity of their interactions cannot be reduced to a few simple formulas. But when evolutionists focus on strategic dynamics, they never fail to consider language. The challenges that humanity will have to face in the 21st century, together with the new possibilities we will be empowered to explore, could generate a new great evolutionary wave. We can therefore assume that language will play a strategic role.

Language is not just a means of conveying information. It is a medium that shapes knowledge. And like every medium, it is itself a message, as Marshall McLuhan would have said. The diversity of languages is an evolutionary phenomenon, as is their transformation over time. As Gaia Vince explains, linguistic diversity is linked to that of the natural habitats in which the peoples of the human species have lived. It is a cultural resource on which humanity depends as much as it does on cooking food; it is essential for the formation of the structure of the brain and thus is a critical factor in human biology. Its functions are articulated: because, in fact, they are together the fruit and cause of evolutionary phenomena. As the evolutionist Telmo Pievani claims: to study evolution is to seek unity in diversity.

Firstly, as with many animals, different languages are signs of belonging and are a hallmark of each society. It applies to killer whales as it does to humans. “Every spoken language changes an individual’s brain, personality, and behavior in subtle ways. The cultural evolution of languages also changes our biology,” says Vince: “Language shapes the way we think. Native English speakers are better than Japanese at remembering who or what caused an accident, such as the breaking of a vase. This is because in English, as in other languages, we say that ‘someone’ broke the vase, whereas in Japanese, the agent subject is rarely expressed, and it is more common to say that the ‘vase broke’. The structures that exist in our language profoundly influence the way we construe reality; we find that reality, and human nature, differ significantly depending on the language we speak”. Different communities are cemented by their languages.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowSecondly, however, language is connected to understanding the world and its changes. Naming things is a window on how we understand things. And because we understand things together with others in a community, the joint naming of things is how knowledge starts. Therefore, while individual words and their signs serve to convey information, language as a whole serves to share meanings by referencing shared contextual knowledge of the complex cultural settings in which communicating subjects congregate. But the contexts themselves, as such, evolve and change. So languages undergo mutations. People develop methods to translate between different languages; they learn to understand and speak the languages of others by becoming bilingual or multilingual, and finally create new languages.

On the whole, languages are changing with globalization and digitalization, which leads humans to live intensely in their own communities and, at the same time, to open up to other communities. With globalization and digitization, humans experience a multiplicity of connections and identities that are local, supranational and global. Consistently, linguistic behavior is diversifying, with a variety of phenomena ranging from the recovery of traditional community languages to the learning of international languages and even the development of new languages.

The words of young people

Those destined to embark on the most complex transformation in human history were born in the last twenty years. They are mainly based in Africa and in regions where development has yet to take full effect, including demographic transition. But throughout the world, they are pursuing their voice and their perspective. Today’s youth is destined to mature in the 21st century, facing unprecedented challenges and relying on means and technologies that previous generations could not even imagine. And they will have to learn how to inquire, communicate, and decide together. How will this generation express itself? What will it try to say? What will it have to learn to communicate in a scenario that will be profoundly different from the past? And how will these young people recall the experience of their predecessors?

Children learn from adults. Teenagers engage with adults and create alternatives. This attitude of theirs is an evolutionary dynamic. It empowers the exploration of the possible, which would be held back if each generation simply stopped short at seeking guidance from the generations that preceded it.

“Language shapes the way we think.”

Gaia Vince –

The language of young people is destined to witness the changes that will accompany the adaptation of cultures to contextual change. By experiencing multiple identities and the various communities to which they belong, young people force language to evolve, changing how information is transmitted, how thoughts are expressed, and memories narrated. They change how society agrees on or disputes perceived contexts and interpretative frameworks. Young people experience the evolution of language in the exchange of stories and art involving them, in the interchange of messages between diverse linguistic contexts, always learning new tools to communicate, adapting to change.

In Ireland, young people are reviving Irish, the country’s ancient language. We see a similar scenario in Nigeria, where on the platforms they use, often in English, youths search for films and music in Yoruba and Hausa, two of the dozens of traditional languages of the peoples in that country. According to the most attentive observers, in Iceland, young people speak to each other in English to distinguish themselves from adults who are naturally surprised when they don’t hear them express themselves in Icelandic. And in South Africa, young people are not opposed to English, which is not seen as the colonial language as in Nigeria, but as a means of expression that opens up the worlds of modernity and democracy desired after the nightmare of Apartheid. In general, young people are the protagonists of the most prominent cultural exploration. In Saudi Arabia, it is young people who are fuelling previously unforeseeable innovations, such as the success of Japanese and Israeli restaurants. In Poland, it is young people who are demonstrating in their hundreds of thousands for a modernization of the social and legal norms regulating sexual behavior and developing digital devices that circumvent censorship. According to a Kantar survey, almost a third of young Poles demonstrated against strict anti-abortion legislation in November 2020. And in South Korea, the push towards more open-mindedness in favor of women’s rights – in a country where 79% of men claim to have abused a woman – is also encouraged on gaming platforms by feminist gamer groups such as Famerz. The cause is also promoted by champions such as Kim Se-hyeon, the first woman gamer admitted to the Overwatch League, and is summed up by feminist author Lee Min-Kyung in the title of her book: ‘We Need a Language’.

Yes indeed. Beyond protests and demonstrations of social-political courage, young people are leading the cultural change, the profound one, the one that remains evolutionary in the mutations of language. Language is one of the dimensions that lends itself most to exploring innovations and creating community among young people. In a book that brings together dozens of examples and research on youth language practices in urban settings, Jacomine Nortier and Bente Svendsen show how the evolution of language is a central element of social innovation. The chapter by Sally Boyd et al. analyses the behavior of young people who speak several languages in Toronto and in a number of Swedish cities; it concludes that there is a tendency to develop (multi)ethnolects, multiethnic dialects, related to the encounter of immigrants and refugees with the culture of young residents. The migration movement is constantly accelerating and is set to grow further. Bente Svendsen points out that in 2013, 3.2% of the world’s population were international migrants, 232 million people and that in the OECD countries, this has more than tripled since the 1960s. Meanwhile, the UN predicts that by 2050, 70% of the world’s population will live in cities, compared to 50% today. The cities of the near future will be unprecedented linguistic cauldrons. Not least because migrants in the digital world are not necessarily condemned to disconnect from their homelands and can cultivate daily relationships with those who have stayed at home through the internet at very affordable prices. The resulting phenomena have great significance. Oslo is the fastest growing city in Europe, and at this point, 150 different languages are spoken in its primary and secondary schools. English is increasingly being used in the executive entourage of business and science, but not in the online conversation space. In that scenario, we observe linguistic hybridization. YouTube is a very useful platform for studying the hybrid and global language used in hip-hop videos.

Henriette Walter is a linguist who has shown how identity languages, even in the most closeted communities and in times with little or no connectivity, have always been receptive to the influences of other languages and have constantly evolved. And as time passes, we find that words pass from one language to another and then back again. So much so that in the end, an international dimension of the vocabulary of many languages develops. Walter studied a multilingual vocabulary for travellers in Europe and found that among the 8,000 essential words for those who need to express themselves in the most populous European countries – English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese – as many as 1,200 are international. And on the other hand, in this set of intertwined languages, among which words of English origin never exceed 5 per cent, even at times of major influence of Anglo-Saxon civilizations, new words never cease to be created to designate new things, while other words die with the realities they referenced. All these changes, Walter points out, are agents that enrich the spectrum of expressive possibility. It is the experience of all multilingual artists: switching from one language to another changes the way of thinking, laughing, worrying. And human awareness is heightened.

Diverse languages express diverse communities, cultures and personalities. We need connective languages to communicate. The contexts are and remain different, but information must flow. And as it flows, it builds new contexts in which people meet, occasionally creating new linguistic forms. Learning to express oneself in this multiplicity of dimensions implies adhering to a form of multilingualism in synchrony with evolution. And this evolutionary multilingualism is essential for communicating in different contexts, those rooted in tradition and those under construction: it is made up of traditional languages, connective languages and emerging neo-languages. Multilingualism reflects the increasingly necessary multiplicity of communication levels. Globalization, even in its new, less economic and more ecological form, and digitalization, based on artificial intelligence and the web3, favor access to a plurality of dimensions of the person, of communities, of national and supranational belonging, of global experiences. Social multidimensionality and cultural multilingualism are the way to fully experience the plurality of identities, enriching unity in diversity.

The way today’s young people communicate, those who will be the adults of 2050 and the elderly of 2070 and who will see how the ecological transition and social inclusion will play out, will have important evolutionary consequences. To face up to the great cultural reshuffle looming in the 21st century, humanity will have to develop an awareness of the plurality of the dimensions of its history. Young people will be the protagonists of this awareness. Evolutionary multilingualism is the tool that preserves and connects different cultures. Biodiversity is wealth and health; its converse poverty and fragility. Languages contribute to building this creative condition by becoming manifold, multidimensional, open, respectful and communicative. Connective languages may serve to facilitate international contexts, but multilingualism augmented by artificial intelligence ensures both togetherness and diversity. The translation system can keep pace by evolving in turn and listening to young people, who are the drivers of change, and by expanding into communication design to ensure respect and inclusion. Ecological transition equates to cultural understanding.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowDevina Heriyanto, Indonesian youths say religion key to happiness, The Jakarta Post, 2018

Olivia Houghton and Lara Piras, Four ways generation z are transforming instagram, Lsnglobal, 2019

Gaia Vince, Evoluzione, Mondadori 2021

Telmo Pievani, La teoria dell’evoluzione, Il Mulino 2017

Mark Pagel, Wired for culture. Origins of the Human Social Mind, Norton 2012; Vince, cit., p. 150-151.

Donna Abu-Nasr, Saudi Arabia’s Social Revolution Arrives at Riyadh Dining, Bloomberg, 2021

Protests against abortion ban backed by vast majority of Poles, The First News, 2020

Jacomine Nortier e Bente Svendsen (edited by), Language, Youth and Identity in the 21st Century. Linguistic Practices across Urban Spaces, Cambridge University Press 2015.

Henriette Walter, L’aventure des langues en Occident, Robert Laffont 1994.

Photo credits: Kiana Bosman, Unsplash / Callum Shaw, Unsplash / Joshua Hoehne, Unsplash