Global Perspectives

July 2024

Key Statistics

- 2nd country with most developed startup ecosystem in Africa

- 3rd larger producer of tea in the world

- 4th among Countries in Africa with High Net Worth Individuals

- 7th in World’s Top Travel Destinations for European Tourists

- 8th among the 28 economies in Sub-Saharan Africa in Global Innovation Index

Kiswahili: a never-ending amalgamation process

In East Africa, nestled between Tanzania and Somalia, lies a country of remarkable diversity in every respect. Named after Mount Kenya, the second-highest peak in Africa at 5,199 meters, the origins of its name are thought to derive from the Kikuyu, Embu, and Kamba words “kirinyaga,” “kirenyaa,” and “kiinyaa,” all meaning “God’s resting place” or “Where God lives.“

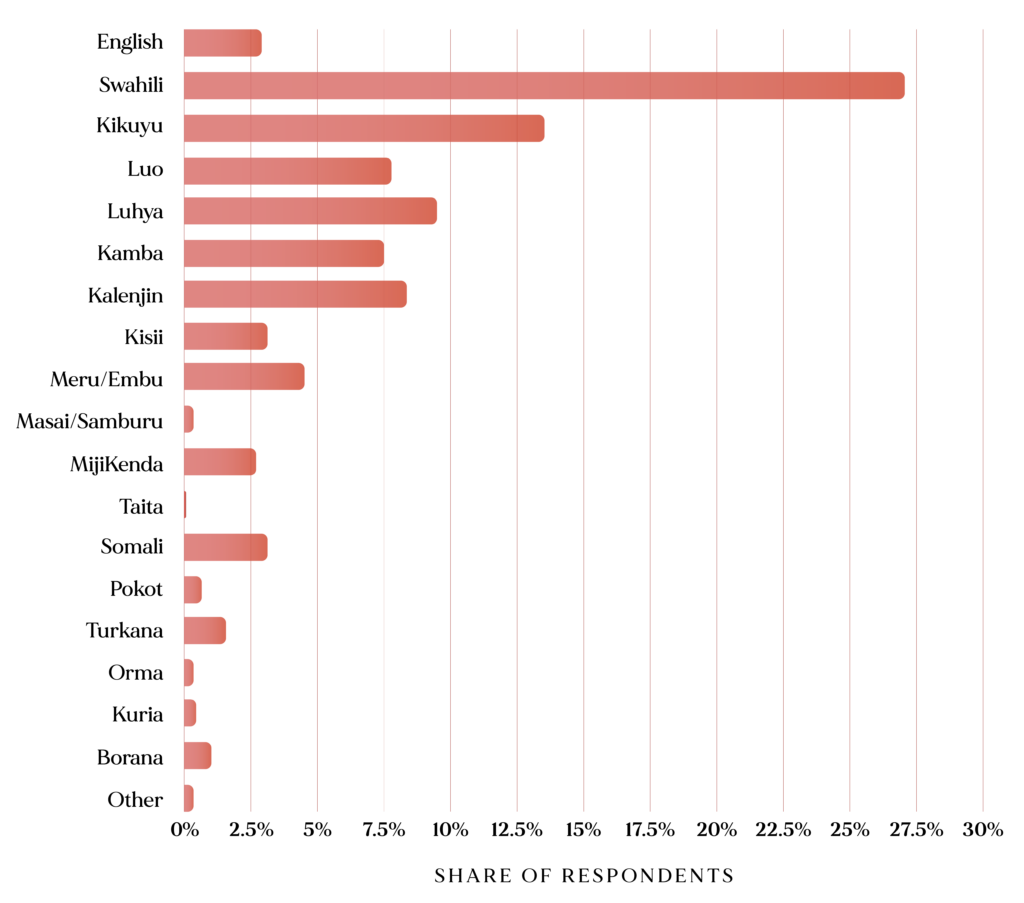

Kenya boasts a total of 68 spoken languages (Ethnologue). This linguistic richness mirrors the country’s diverse population, encompassing major ethno-racial and linguistic groups found across Africa. Kenya’s indigenous peoples, comprising nearly the entire population, are categorized into three language groups: Bantu, Nilo-Saharan, and Afro-Asiatic. Each ethnic group typically uses its mother tongue within its respective communities.

- Bantu is by far the largest, with its speakers mainly concentrated in the southern third of the country, in the fertile Central Rift highlands and the Lake Victoria basin.

- Nilo-Saharan—represented by the Kalenjin, Luo, Maasai, Samburu, and Turkana languages—is the next-largest group. The rural Luo inhabit the lower parts of the western plateau, while the Kalenjin-speaking people occupy the higher parts of it. The Maasai are pastoral nomads in the southern region bordering Tanzania, and the related Samburu and Turkana pursue the same occupation in the arid northwest.

- The Afro-Asiatic peoples, who inhabit the arid and semiarid regions of the north and northeast, constitute only a tiny fraction of Kenya’s population.

Kenya’s linguistic landscape is not only diverse, but also harmoniously coexists within a country marked by never-ending cultural and linguistic amalgamation.

English and Swahili are the two official languages:

- English holds the status of official language, though only 3.4% of Kenyans use it as their primary home language. British English predominates in Kenya, but there is also a distinctive local dialect known as Kenyan English, infused with unique elements derived from Bantu languages like Kiswahili and Kikuyu. This dialect has evolved since colonial times and now incorporates some American English elements.

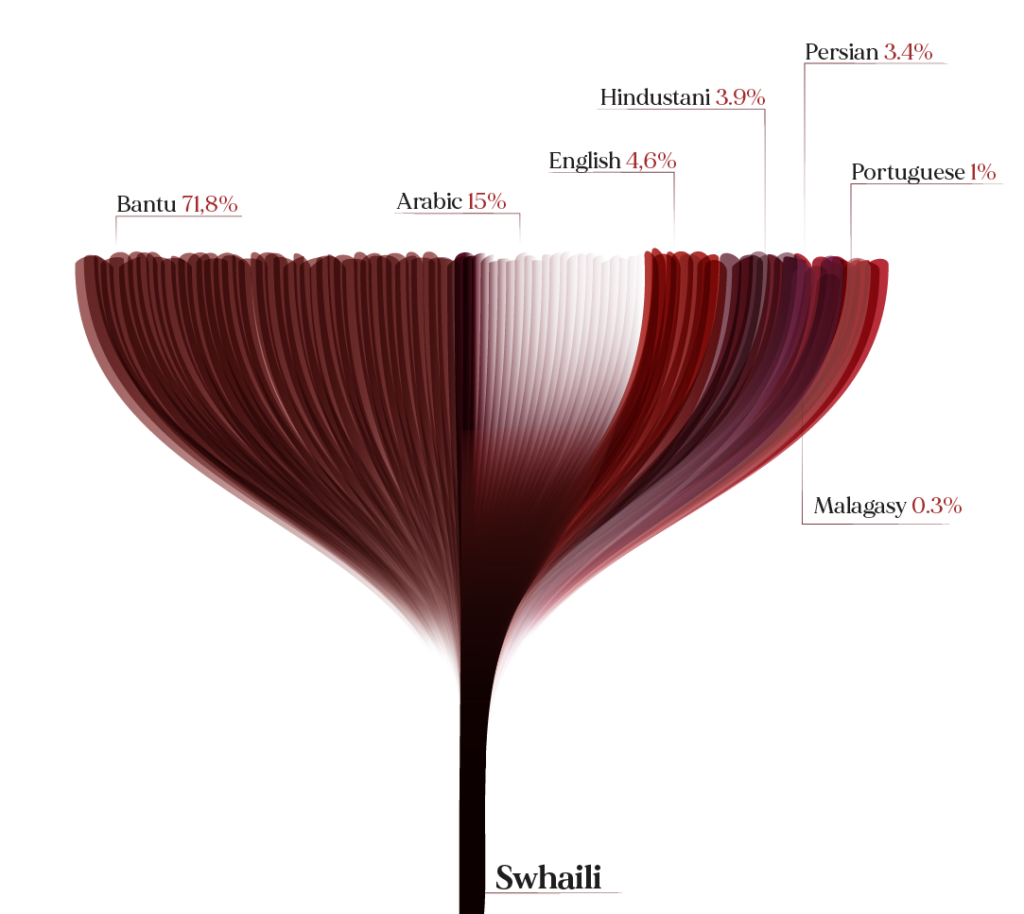

- Swahili is recognized as the national language and serves as the lingua franca because it best represents the amalgamation process of living in the country. The language evolved from local Bantu languages and incorporates Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Hindi, and English influences. The Swahili community, largely descendants of intermarriages between Arabs and Africans, predominantly resides along the coast.

Distribution of primary languages spoken at home in Kenya

Source: Statista, 2021

The Origins of Swahili Loanwords

Source: Wikipedia

Harambee or “Pulling together”

Kenya is a source of both immigrants and emigrants, as well as being a host country for refugees.

Immigrants

In addition to its African population, Kenya is home to communities that immigrated during British colonial rule. In particular, significant Asian migration occurred between 1896 and 1901, when around 32,000 indentured laborers were brought from British India to build the Kenya-Uganda Railway. The majority of Kenyan Asians hail from the Gujarat and Punjab regions. The community grew significantly during the colonial period, and in the 1962 census Asians made up a third of the population of Nairobi and consisted of 176,613 people across the country. Since Kenyan independence, many Asians have emigrated due to race-related tensions with the Bantu and Nilotic majority. Those that remain live in urban areas such as Kisumu, Mombasa, and Nairobi and are principally concentrated in the business sector. Asians continue to form one of the more prosperous communities in the region. European Kenyans, meanwhile, are mostly British in origin and are the remnants of the colonial population.

Emigrants

In the 1960s and 1970s, Kenyans pursued higher education in the UK due to colonial ties, but as British immigration rules tightened, the US, the then Soviet Union, and Canada became attractive study destinations. Later, a stagnant economy and political issues in the 1980s and 1990s led many Kenyan students and professionals to seek permanent opportunities in West and Southern Africa.

Host country

Nevertheless, Kenya’s relative stability since its independence in 1963 has attracted hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing violent conflicts in neighboring countries. In 2020, the top three countries with migrants in Kenya were Somalia (44%), Uganda (30%), and South Sudan (13%) (IOM, UN Migration – 2020). Kenya was sheltering nearly 280,000 Somali refugees as of 2022.

For this reason, the country is home to a unique cultural tapestry where people proudly embrace their individual cultures and traditions while recognizing the importance of national solidarity. This spirit is embodied by the motto “Harambee” (Swahili for “Pulling together”), which has been emphasized by Kenya’s government since independence.

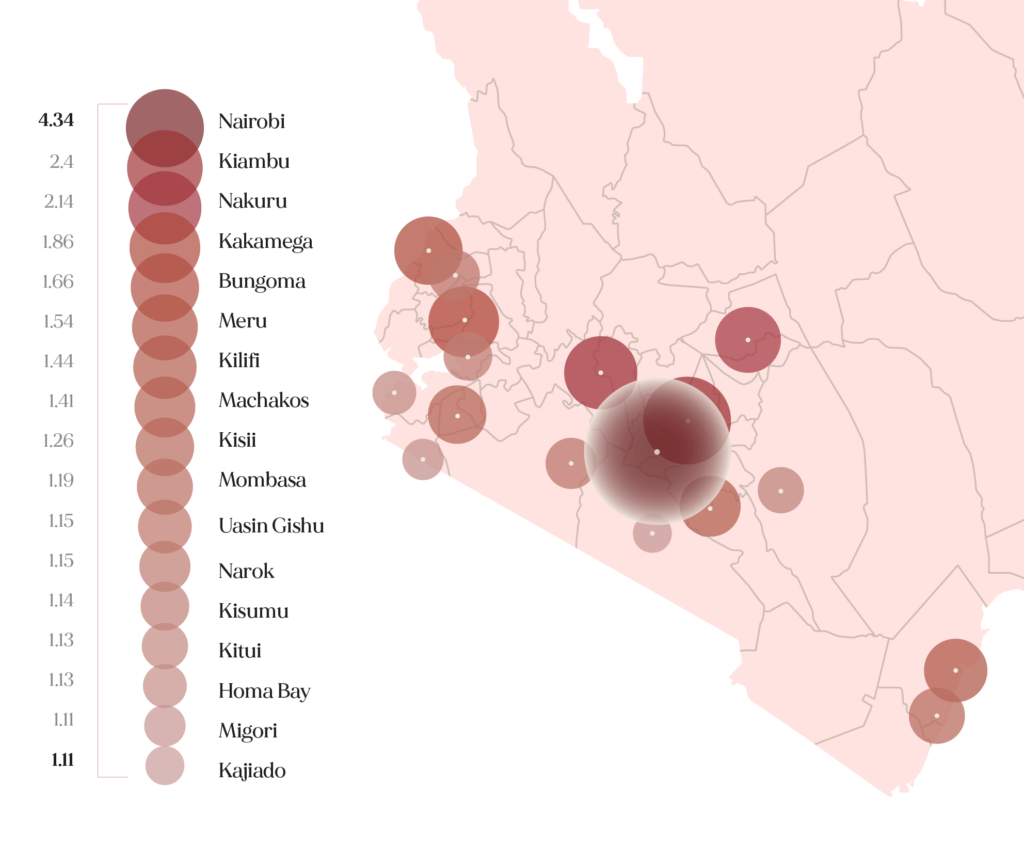

The downsides of this growing population—in particular, Kenya’s accelerating population growth from the early 1960s to the early 1980s—are numerous. First of all, it has seriously constrained the country’s social and economic development. During the first quarter of the 20th century, the total population was less than 4 million, largely due to famines, wars, and diseases. By independence in 1963, it had grown to more than 8 million and continued to increase rapidly. From 1960 to 2022, Kenya’s population rose from 8.12 million to 54.03 million, a growth of 565.4% in 62 years (Worlddata.info, 2024). By the mid-1980s, the growth rate began to slow dramatically, but in the early 21st century, the rate of natural increase was still above the world average, making Kenya the second most populous country in Africa after Nigeria.

The pressure of this population explosion led to limited employment opportunities, rising costs for education, health services, and food imports, and an inability to generate the resources to build housing in both urban and rural areas. The most significant causes of the country’s explosive population growth were a sharp fall in mortality rates—especially infant mortality—and the traditional preference for large families. This is why, in 1967, Kenya became the first sub-Saharan country to launch a nationwide family planning program: government initiatives and international technical support spurred Kenyan contraceptive use, decreasing the fertility rate (children per woman) from about 8 in the late 1970s to less than 5 children 20 years later. As of 2022, it has plateaued at about 3 children.

From 1960 to 2022, Kenya’s population rose from 8.12 million to 54.03 million, a growth of 565.4% in 62 years.

Moreover, the growth of Kenya’s population, currently at about 55 million, has contributed to the country’s inadequate supply of new housing units. The annual housing demand is 250,000 units, but only an estimated 50,000 units are supplied. The proportion of the total population living below the international poverty line is 29.4%, with an unemployment rate of 5.5%, according to the World Bank. Housing affordability is a major challenge in Kenya, and many people cannot afford to buy or build their own home. About 6.4 million people from Kenya’s urban population live in informal settlements, while an estimated 60% of the capital city Nairobi’s residents live in slums (Habitat.org), a substantial increase from 33% four decades ago.

Total population of Kenya by county (in millions)

Source: Statista

It’s all about a cup of tea

Kenya’s agricultural sector is the backbone of its economy, contributing about 33% of the country’s GDP and employing over 40% of the total population and 70% of the rural population (USAID, 2023). While its share of GDP has declined from more than two-fifths in 1964 to less than one-fifth in the early 21st century, agriculture remains crucial. It provides raw materials for manufacturing and generates tax revenue and exports, supporting the broader economy.

This central role has been determined by different public policies which, since independence in 1963, have shaped the country’s economic development through various regulatory powers. One of the government’s major focuses has been the redistribution of land used for agricultural exports. The aim of this policy was to achieve economic growth, ensure stability, generate employment, and maximize foreign earnings. However, Kenya continues to face substantial challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, limited access to water, and a scarcity of arable land. Despite the importance of agriculture, the sector faces challenges like water scarcity, inadequate infrastructure, and limited arable land: less than one-tenth of Kenya is suitable for farming, and government efforts to increase irrigation have only developed 20-25% of potentially irrigable land.

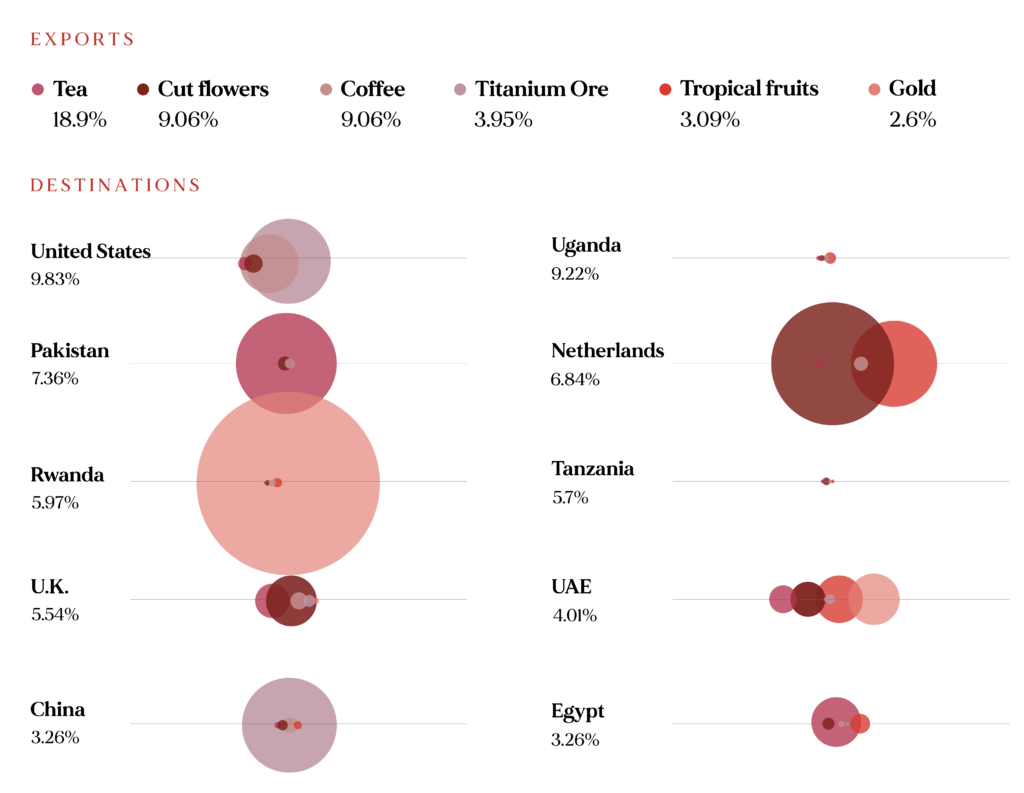

Total exports and their destinations, Kenya (2022)

Source: OEC

Tea and fresh flowers are Kenya’s primary export earners. Coffee is another key product: it was historically an important source of export income and still contributes to the economy, but it began declining in importance and income in the 1990s, owing in part to market instability and deregulation. When it comes to flowers, Kenya supplies the majority of the world’s pyrethrum, a flower used to create the non-synthetic pesticide pyrethrin. Demand for this product fluctuates depending upon the level of interest in the United States, which is the largest consumer of this commodity.

In a bid to reduce its dependence on volatile agricultural markets, Kenya has diversified its exports since the late 20th century, adding horticultural products, clothing, cement, soda ash, and fluorspar. Soda ash, used in glassmaking, is Kenya’s most valuable mineral export and is quarried at Lake Magadi in the Rift Valley. Limestone deposits on the coast and inland are exploited for cement manufacturing and agriculture. Vermiculite, gold, rubies, topaz, and salt are also important, as is fluorite (also known as fluorspar and used in metallurgy), which is mined along the Kerio River in the north. Deposits of titanium and zirconium-bearing sands have been discovered northeast and south of Mombasa, while petroleum exploration has met with limited success.

Kenya’s economic development is closely tied to its energy resources. Since independence, the focus has been on hydroelectricity. However, access to energy is limited in rural areas, with most electricity consumed by Nairobi and Mombasa. Geothermal resources in the Rift Valley have been harnessed since the early 1980s to generate electricity, supplying a significant portion of Nairobi’s needs. Meanwhile, electricity production from renewable sources (excluding hydroelectric) has surged by 286.4%, rising from 12.5% of total electricity production in 1995 to 48.3% in 2015 (World Bank).

Kenya

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!“Silicon Savannah” on the world stage

The Constitution of Kenya, 2010 represents a milestone in the country’s political history, emerging in response to the acute crises that marked the 2007 elections and the violent post-election conflict of 2008. The disputed 2007 elections, marred by allegations of electoral fraud, sparked large-scale ethnic and political violence, resulting in over 1,000 deaths and hundreds of thousands displaced.

This period of chaos highlighted serious deficiencies in Kenya’s political system, including centralized power, endemic corruption, and a lack of trust in institutions. The new constitution, adopted in 2010, was designed to address these structural issues. It introduced devolution, transferring significant powers to the governments of the 47 counties to promote more equitable and inclusive governance. This reform aimed to correct regional disparities and mitigate ethnic tensions by decentralizing power and bringing resource management closer to local communities. Additionally, the constitution established a range of fundamental rights, such as access to education and healthcare, thereby ensuring greater protection for all citizens. It has led to increased civic participation and improved governmental transparency and accountability, making Kenya’s constitution one of the most progressive and comprehensive among all African countries. However, the transition to a devolved system has faced logistical and political challenges, including combating corruption at the local level and the need to build administrative capacity in the counties.

In the years following the adoption of the 2010 Constitution, Kenya has carved out a prominent position in the global arena and assumed a strategic role within the African continent. This positioning has been demonstrated through a combination of active diplomacy, participation in international and regional organizations, and the development of key partnerships with various nations and economic blocs.

Kenya has gained significant influence in East Africa and the continent overall, leveraging its strategic geographic position, robust economy, and relative political stability. Nairobi, its main hub, serves as a regional center for trade and finance, hosting prominent international organizations like the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the United Nations Office at Nairobi (UNON), thus bolstering its diplomatic status. Kenya is a key member of the East African Community (EAC), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and the African Union (AU). As such, it plays a crucial role in promoting peace, security, and regional integration, filling the leadership gaps left by neighboring countries.

Its relationship with China has grown exponentially over the past two decades, becoming a cornerstone of Kenya’s foreign and economic policy. China has invested heavily in the country’s infrastructure, financing and constructing key projects such as the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) connecting Mombasa to Nairobi. These investments, often made through loans with favorable terms, aim to improve connectivity and stimulate economic growth. However, being heavily indebted to China has raised concerns about the country’s debt sustainability and economic dependence. Meanwhile, Kenya is stepping up its efforts to attract foreign direct investment, aiming to double investment to $1.6 billion this year. Over 600 Chinese companies took part in the China-Africa Economic Trade Expo in Nairobi, resulting in significant agreements in sectors such as agro-processing, healthcare, and cold storage solutions. These investments aim not only to create thousands of jobs but also to leverage key value chains such as macadamia nuts and the fisheries sector.

The partnership between Kenya and the United States is long-standing, rooted in economic and military cooperation and the promotion of democracy. The United States is a major provider of development aid, investing in critical sectors such as healthcare, education, and security. Additionally, the US has praised Kenya for its commitment to democracy and renewable energy, recognizing it as the leading democracy in East Africa.

By maintaining a position of strategic neutrality, Kenya has successfully established relations not only with the United States but also with other global players like the European Union, India, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, balancing diversified interests and contributing to regional stability and international cooperation.

Foreign investments in technology and telecommunications, agriculture, renewable energy, infrastructure, and manufacturing are motivated by Kenya’s strategic position as a gateway to East and Central Africa, its relative political stability, and its growing consumer market.

The relationship between Kenya and the UAE has intensified, primarily driven by trade and investments. The partnership extends to energy and tourism cooperation, with significant initiatives in digital innovation and renewable energy. A notable investment of $1 billion is intended for projects including a state-of-the-art data center campus powered by renewable geothermal energy and water conservation technology. This investment not only promotes the development of cutting-edge technology in Kenya but also strengthens the country’s position as a regional hub for digital innovation in Africa.

Collaboration with international partners like the UAE indicates Kenya’s increasing global interconnectedness in the tech sector, offering significant opportunities for long-term economic and technological development. The growth of this sector, with Nairobi dubbed “Silicon Savannah,” has attracted international investment, while initiatives like M-Pesa—a money transfer service for mobile phone users launched in 2007 on the Safaricom mobile network—have revolutionized the financial system, increasing financial inclusion and stimulating economic growth.

Foreign investments in technology and telecommunications, agriculture, renewable energy, infrastructure, and manufacturing are motivated by Kenya’s strategic position as a gateway to East and Central Africa, its relative political stability, and its growing consumer market. Multinational companies such as Microsoft, Google, General Electric, and Coca-Cola are among the top investors in the country. Building on this progress, Kenya is aiming to surpass $4.6 billion in foreign investment in 2024, an ambitious goal that reflects growing confidence from international investors in the country’s economy.

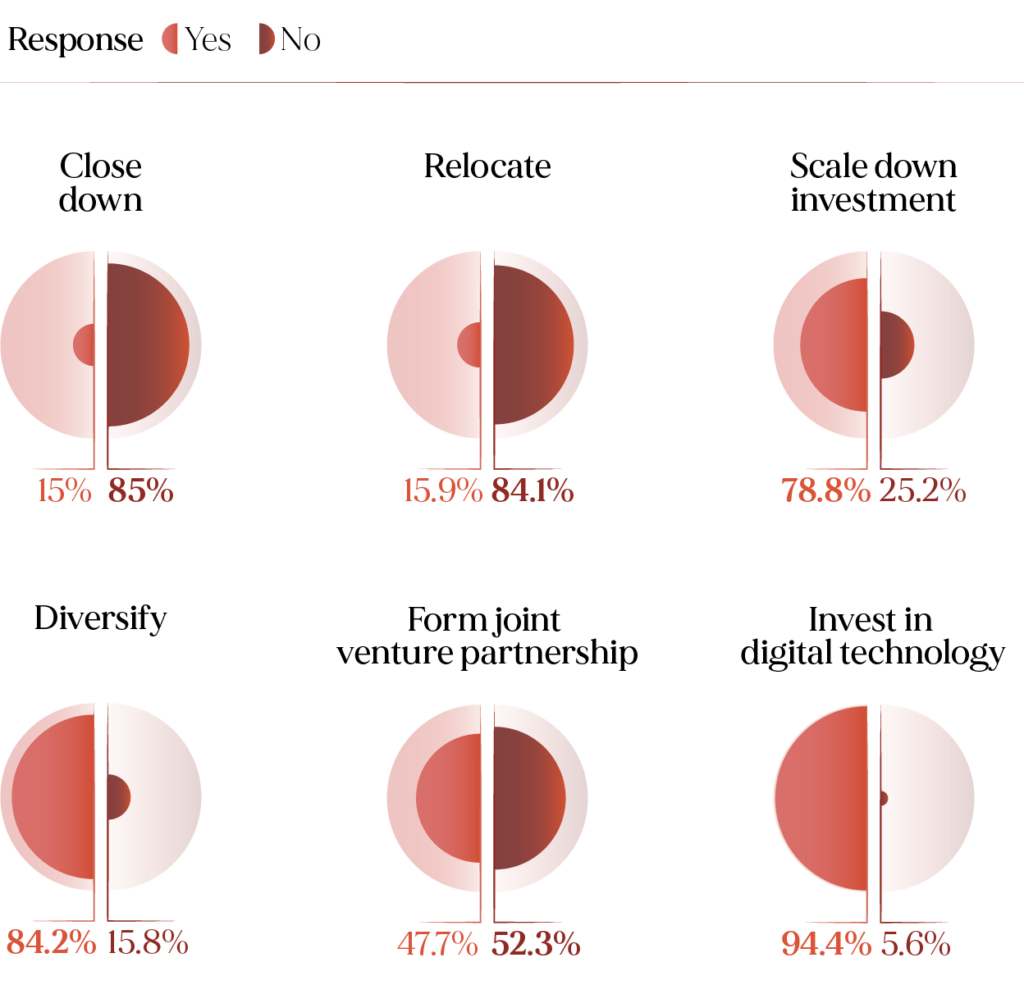

Foreign investors’ perception of the business environment in Kenya after the Covid-19 pandemic

Source: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2023

Despite efforts to equip new generations with tech skills through the introduction of computing courses in schools, Kenya faces challenges related to brain drain and the poaching of talent by large international companies offering salaries beyond the country’s economic reach. This scenario raises important considerations on balancing technological development and economic sustainability.