Global Perspectives

January 2025

Key Statistics

- Highest GDP in Africa (Statista, 2024).

- 1st in Africa and 11th globally for English proficiency (English Proficiency Index).

- 3rd in Africa for tech startup funding secured in 2023 (Statista, 2023).

- 2nd among Sub-Saharan African countries on the Global Innovation Index (WIPO, 2024).

- World’s top platinum producer, supplying 80% of global output (Reuters, 2023).

At the Centre of the Global South?

In 2025, South Africa will make history as the first African nation to preside over the G20, marking a pivotal moment on the global stage. At a time when Pretoria faces the challenge of maintaining its leadership within BRICS—especially after the inclusion of Egypt and Ethiopia—the G20 presidency offers a strategic platform to reaffirm its position as a regional leader.

As a BRICS member since 2010, South Africa plays a prominent role in global geopolitics, despite its comparatively modest economic size within the bloc. With a GDP of $377 billion in 2023, ranked 37th globally (OEC, 2022), it represents just 2.5% of BRICS’ total economy, dwarfed by China’s $17.7 trillion and India’s rapid growth. This economic disparity underscores the country’s vulnerability within the bloc. However, its outsized geopolitical presence raises a compelling question: why has South Africa’s central position in global affairs been further cemented despite its ongoing growth struggles?

The answer lies in South Africa’s unique ability to bridge the West and the Global South, leveraging its strategic location, abundant natural resources, and moral leadership. This role has enabled it to foster cooperation among emerging powers and shape Africa’s position in the global economy, promoting a multipolar world that challenges Western dominance. Through its advocacy on economic governance, climate change, and inclusive development, South Africa has become a global voice for social justice. Central to this is its green agenda, focused on renewable energy and sustainability.

Why has South Africa’s central position in global affairs been further cemented despite its ongoing growth struggles?

On the other hand, South Africa’s moral authority, rooted in its history of resistance against apartheid and its dedication to human rights, further bolsters its global preeminence. So even though its economy grows at a slower pace compared to other BRICS members, South Africa is a beacon of resilience and innovation on the continent. With a population of 64 million (Worldometers, 2025) and 12 official languages, despite being Africa’s second-largest economy after Nigeria, South Africa’s true strength lies in its economic diversification and pluralism.

Shifting focus to South Africa’s economic strengths, the nation’s wealth in natural resources remains crucial to its economic power. As the world’s leading producer of platinum, supplying over 70% of global demand (Mining Technology, 2024), and a key player in the extraction of chrome and manganese—vital for green technologies—South Africa continues to exert significant influence. Gold, platinum, and diamonds remain vital to its economy, with the mining sector accounting for around 6.2% of GDP and contributing 58% of total exports (PwC, 2023).

However, South Africa is no longer synonymous with just mining: the technology and financial services sectors, together constituting 73% of the GDP (International Trade Administration, 2024), are on an upward trajectory. Johannesburg, home to the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), one of the world’s top 20 largest by market capitalization, serves as the financial sector’s heartbeat with a stock market valued at $1.28 trillion and banks managing assets over $1.41 trillion. Simultaneously, Cape Town is emerging as Africa’s Silicon Valley—also known as “Silicon Cape”—attracting significant investments into the tech startup sector. In the 2022-23 period, South African startups raised over $500 million (Africa Private Equity, 2024), primarily in fintech, e-commerce, and renewable energy sectors, demonstrating a rapidly expanding innovative ecosystem. Specifically, technological innovation plays an increasingly central role in South Africa’s economy. Both Cape Town and Johannesburg not only attract startups and venture capitalists but also host incubators and accelerators that stimulate the growth of innovative businesses. These tech startups contribute economically and socially, creating solutions for local problems like access to education and financial services in rural communities. However, the digital divide and limited internet connectivity in less developed areas pose significant obstacles to inclusive technological growth.

Furthermore, manufacturing, which contributes 13.9% to the GDP (PwC, 2024), is highly diversified, including the automotive industry, where brands like BMW, Ford, and Toyota use South Africa as a production hub for global exports. Similarly, agriculture, despite representing less than 3% of the GDP (Trading Economics, 2023) and being subject to various challenges like cyclical droughts and often inadequate infrastructure, is crucial for the export of premium products like wine, citrus fruit, and grapes, placing the country among global leaders in these sectors and generating more than $2 billion in annual revenue. Not less important is tourism, which pre-pandemic accounted for about 7% of the GDP and is now slowly regaining ground, attracting visitors enchanted by the beauty of Kruger National Park and the iconic Table Mountain.

This economic success, however, doesn’t obscure the significant challenges South Africa faces. Unemployment, which reached 32.1% in 2024 (Trading Economics), ranks among the highest in the world, with even higher rates among the youth. Social inequality, with a Gini coefficient among the highest globally, reflects a deep divide between a wealthy minority and the 55% of the population living in extreme poverty. Furthermore, access to quality education remains limited, perpetuating a cycle of poverty that the government struggles to break. Years of austerity policies have limited public investments in key sectors such as health, education, and infrastructure, while the energy crisis, fueled by the inefficient management of the state-owned company Eskom, has led to regular blackouts known as “load shedding,” causing estimated economic losses in billions of dollars and undermining the country’s competitiveness.

Despite these difficulties, South Africa maintains a uniquely strategic position on the global stage. Its infrastructure network, comparable to OECD standards, makes it a vital logistics hub for accessing sub-Saharan markets, while its hybrid economy, combining capital-intensive sectors with competitive labor costs, attracts foreign investments. The country ranks 82nd in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, the best among major African markets, thanks to business-friendly policies and regulatory transparency that facilitates business start-up and management. A crucial competitive advantage is the spread of the English language: spoken by 8.7% of the population as a first language and over 35% as a second language (Read more about by Luca De Biase for Imminent), it is a crucial asset in a country with 12 official languages. It is the main vehicle for international trade, higher education, and diplomatic relations, facilitating global exchanges and attracting multinational companies.

Humans and AI: the challenge of languages in Africa

Imminent Unconference in South Africa

Cape Town, October 24th-26th, 2023. 36 leaders in the language, translation, localization, and artificial intelligence industries came together for the second edition of the Imminent Unconference – after the first edition in London & Southampton – on the theme of “What should language AI be in Africa?”.

Read it now!Looking to the future, South Africa has the opportunity to redefine its role not only as an African economic powerhouse but also as a global model of sustainability and inclusivity. Strategic investments in education, healthcare, and green infrastructure, along with fiscal reforms and policies aimed at reducing inequality, could transform current challenges into opportunities for sustainable growth. The legacy of a complex past continues to present significant challenges, yet within these lies the country’s greatest asset—its diversity. This unique strength is positioning South Africa at the heart of the Global South, driving its rise as a powerful and influential force on the world stage.

Source: World Bank

Rainbow Nation

“What is our land without a language?” asks Magdalena Kassie, a South African activist who has played a crucial role in recent years in promoting the language among young ǂKhomani and the broader community. In a multilingual South Africa, she is not alone in posing this deceptively simple and emblematic question, fighting to save a language at risk of extinction. Alongside her, the nonagenarian Hanna Koper is also participating in efforts to preserve an ancient African language. She and her two sisters are considered the last speakers of the San N|uu language, classified by UNESCO as critically endangered. N|uu has been transmitted orally but never codified and now, Koper and her siblings are the last able to speak it and they’re working with linguists to create alphabets with over 45 clicks, 30 non-click consonants, and 37 vowels. This preservation work is carried out alongside Matthias Brenzinger, director of the Centre for African Language Diversity at the University of Cape Town who describes N|uu as the most indigenous language of Southern Africa. At-risk languages are not limited to a few, and many of them are experiencing revitalization efforts, which are emblematic of a country where language has historically been a battleground and is today a source of pride and national identity.

Modern South Africa carries with it the legacy of centuries of colonialism and apartheid. The transition to a democracy in 1996 ushered in one of the world’s most progressive constitutions, building the country’s development on the concept of rainbowism, coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 1994. This concept embodies the harmonious coexistence and collaboration among ethnically and culturally diverse peoples. One of the most evident manifestations of this concept is the extraordinary linguistic variety: with the inclusion of South African Sign Language in 2023, the country recognizes 12 official languages. In the past, Afrikaans (of Dutch origin) and English dominated, marginalizing the African languages spoken by over 80% of South Africans. However, with the new constitution, while more than thirty languages are spoken across nine provinces, the official recognition of these twelve languages represents a response to the past of racial segregation and an acceptance of the country’s multicultural reality.

The concept of rainbowism embodies the harmonious coexistence and collaboration among ethnically and culturally diverse peoples.

Among the twelve official languages, two are European while nine originate from the Nguni-Tsonga and Sotho-Makua-Venda linguistic families, related to the expansion of the Bantu peoples from West Africa. IsiZulu is the most spoken language, followed by IsiXhosa; together, they are spoken by over 40% of the population. On the other hand, Afrikaans and English, each spoken by 8% to 10% of the population (Stats SA, 2022), are primarily used by white and “coloured” South Africans, maintaining a central role in institutions, the economy, and culture. There are two interpretations of why the country chose to officially recognize so many diverse languages. The first highlights the country’s commitment to promoting its multiethnic character by breaking with the legacy of apartheid. The second suggests that at the dawn of the new democracy, there was pressure to recognize only English due to its international importance. However, this might have sparked strong opposition from the Afrikaans-speaking area, so in line with rainbowism, the decision was made to include not only both European languages but also the African ones. The true historical dynamic behind this choice is unclear; more likely, the decision was influenced by many aspects simultaneously. What is certain is that South Africa is a unique example of official coexistence between different languages, making it truly multilingual.

The Evolution of South Africa’s Official Languages: 2001-2022

Source: Stats SA, 2022

Specifically, the South African population is characterized by widespread linguistic diversity and code-switching, meaning the frequent use of multiple languages within the same conversation. In fact, each South African citizen uses an average of 2.84 languages (South African Gateway): although some speak only one language, many others speak three, four, or even more. For instance, most of the black population speaks English and Afrikaans, essential languages in institutions and education, alongside indigenous mother tongues, which belong to the same language families and therefore allow speakers to understand some of the other languages within the same group.

The coexistence of different languages enhances the cultural agility of the country, with no single official language alone able to meet everyone’s needs. English, for example, is the first language for only 8% of the population concentrated in urban areas, though it is widely spread as a second language. Conversely, indigenous languages like IsiZulu, despite their prevalence, are less used in business and experience slower linguistic development and dissemination. In many contexts, they can also be cumbersome with extremely long terms and lack words for the digital age, leading to the inclusion of English terms in conversations.

Therefore, it is understandable that English, a predominant language in major cities like Durban and Johannesburg, remains widely used as a second language. Despite the 1996 Constitution promoting parity among all the officially recognized languages, English is effectively the lingua franca for business, media, education, and institutions. It has been an official language since 1910 and is taught in all schools, along with Afrikaans. Its spread is not only practical for cementing relationships between the different local communities and numerous migrants but also an economic lever toward global markets. Hence, learning English in South Africa is a priority, not an option: it becomes crucial for finding employment, accessing education, or feeling like an integral part of society.However, the hegemony of English poses a concrete threat to the survival of indigenous languages, which are witnessing a continuous decline in the number of speakers, endangering their existence. For instance, Ndebele and Tshivenda are among the least spoken languages in South Africa, with only 2.1% and 2.4% of the population respectively. These languages, recognized by the constitution, are among the most isolated and closely linked to languages of neighboring countries, approaching a dangerously similar fate to other indigenous languages in the region. Despite the clear legal support for South Africa’s official languages, there are significant obstacles to their equitable promotion and conservation. In fact, the predominance of English and Afrikaans in education, media, and business often marginalizes other languages. This linguistic hierarchy could erode less widespread languages, as new generations might favor languages with greater economic opportunities. Furthermore, there is often a lack of resources for language development, including school texts, literature, and qualified educators. This results in inadequate representation and support for certain languages, perpetuating inequalities. In the rainbow nation, where multiculturalism has been a fundamental asset for the country’s economic growth and building its global reputation, the exacerbation and multiplication of disparities between people, languages, and ethnicities poses a significant question: has South Africa truly managed to abandon the legacy of apartheid?

South Africa

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!The Long Shadow of Apartheid

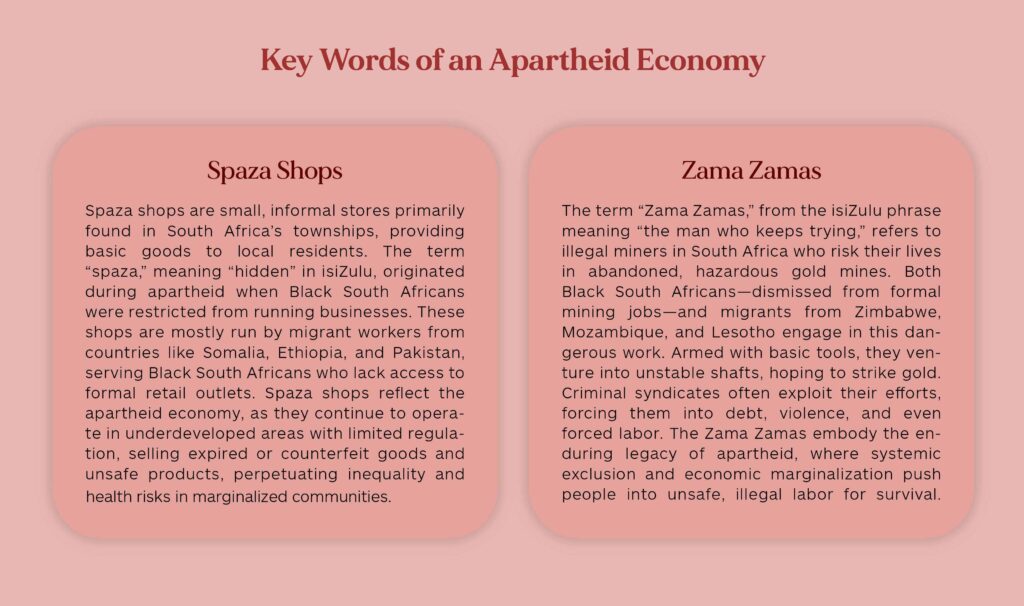

The term “apartheid” originates from Afrikaans, combining “apart” (separate) with the suffix “-heid,” akin to the English “-hood.” Rooted in South Africa’s history and politics, the term is consistently used across its twelve official languages. Interestingly, languages like IsiZulu and IsiXhosa employ uhlangano, meaning “racial segregation,” while Setswana uses karolano ya bosetšhaba, translating to “national segregation.” The word encapsulates one of the most infamous systems of racial segregation, officially institutionalized in 1948 after centuries of colonization that divided society into whites and everyone else—including the Black majority, Indian and Asian migrants, indigenous people, and mixed-race communities. These policies rigidly separated racial groups, relegating Black South Africans to the lowest societal rung. Restricted in movement and confined to small, arid parcels of land called bantustans or “homelands,” Black people endured severe repression, while the white minority thrived on wealth from South Africa’s rich mineral resources. Global protests and activism eventually toppled the apartheid regime in 1994, leading to Nelson Mandela’s election as the nation’s first democratic president, who promised “a better life for all.”

Legally and politically, South Africa has undergone significant transformation. Today, people of all races are deemed equal under the law, free to live, work, and marry without restriction. Black South Africans have democratically governed under the ANC for 30 years, a stark contrast to the apartheid era when voting was illegal for people of color. Yet apartheid’s legacy remains entrenched, particularly in economic and spatial terms, contributing to the World Bank labeling South Africa as the most unequal country globally in 2022. According to its report, around 10% of the population controls 80% of the wealth (World Bank). Meanwhile, the 2022 census, using colonial-era categories, shows Blacks at 81.4%, Coloureds at 8.2%, Whites at 7.3%, and Indians at 2.7%. These figures suggest that the vast Black majority still lack access to wealth and remain marginalized.

The “rainbow nation” slogan seems to have faded along with Emeritus Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Personal incidents of racism remain in the headlines, and structurally, social class is still largely defined by skin color. Although Black individuals now make up just over half of the country’s middle class, extreme poverty remains predominantly a Black experience. Racial issues continue to sow division. Socioeconomically, South Africa’s Statistics Agency reports that Black families earn, on average, three times less than white families (Business Standard). Additionally, while Black individuals constitute 80% of the employable population, they hold only 16.9% of managerial positions. Conversely, Whites—comprising about 8% of the employable population—occupy 62.9% of these roles (Employment and Labour Department SA).

Source: Reuters

Land ownership is another contentious issue, rooted in apartheid’s dispossession of Black landowners. The ANC government initiated land redistribution programs aimed at transferring 30% of farmland to Black ownership by 2030. Yet progress has been slow, with only 20% of farmland redistributed since 1994. Current estimates suggest white farmers still own 78% of farmland with private title deeds—roughly half of all land in South Africa (The Conversation). On the other hand, population shifts since 1996 have also reshaped urban demographics. For example, Cape Town, once predominantly white, saw its Black population grow from 25% in 1996 to 43% in 2016 (Centre For Sustainable Cities, 2020). However, townships remain racially homogenous and underserved, resembling their apartheid-era form. Many lack basic services like water and electricity and are far from schools and hospitals, perpetuating cycles of poverty and exclusion.

In particular, although the apartheid-era Bantu education system, which aimed to provide inferior education to Black children, has been abolished and enrollment increased, schools remain largely inaccessible to rural and low-income communities. A 2019 IMF report found that 75-80% of the poorest primary students relied on “dysfunctional” public schools with limited resources and less qualified teachers (Reuters). Most of those schools were found in Black townships and rural areas. Meanwhile, the public healthcare sector—serving the majority of the population—is overburdened and deteriorating, while a privileged minority accesses superior care through private insurance. The challenges posed by HIV/AIDS and later by COVID-19 have further strained the healthcare system. Examining today’s life expectancy by race, non-Black people average 72.7 years, whereas Black South Africans average 62.2 years (Social Policy Initiatives SA).

All these elements of South African society highlight that, despite apartheid seemingly ending decades ago, the polarization between the white and Black majority significantly impacts not only on the human dimension of the citizens’ lives but also the country’s sluggish economic growth. In particular, South Africa’s GDP per capita steadily increased in the years following the advent of democracy, but this trend reversed starting in 2011. By 2023, it had fallen below the average for emerging markets. Since 2012, South Africa’s GDP growth has averaged just 0.8% per year (National Treasury, 2024)—a rate that, according to the National Treasury, is insufficient to reduce the high levels of unemployment and poverty.

Moreover, the binary narrative of white/Black and us/them has also influenced the social recognition of other ethnic categories. This is the case for Coloured South Africans, a broad category traditionally encompassing those who could not be classified as either white or Black. Coloured people predominantly reside in the Cape region, and their genetic heritage often reflects a blend of up to 140 different ethnicities. It’s important to note that today, not all people of mixed racial descent in South Africa identify as ‘Coloured.’ Some prefer to identify as ‘Black,’ ‘White,’ Indian, or indigenous South Africans, reflecting their newfound freedom of choice. However, during apartheid, the government legally imposed this categorization on anyone of mixed descent. As a result, the ‘Coloured’ identity, while extremely diverse, is primarily rooted in shared history and community rather than specific language or traditions. Though many in this group speak Afrikaans as their first language, it is not a defining trait for all. This category includes many Indian and Chinese migrants, children of mixed-race couples, as well as indigenous groups present in the country.

Indigenous populations in South Africa make up about 1% of the total population: the Khoe-San, comprising the San and Khoikhoi, are the country’s first peoples. During apartheid, both groups were classified as ‘Coloured,’ but since the end of racial categorization, many have reclaimed their identity as Khoisan. Despite this recognition, three decades after apartheid, the Khoi-San continue to be sidelined in land restitution efforts. They face systemic barriers in reclaiming ancestral lands and preserving their cultural heritage. A powerful act of resistance emerged in 2020 with the occupation of Knoflockskraal, near Table Mountain. What began with seven people grew into a movement of over 4,000, reclaiming 1,800 hectares of land deeply significant to the Khoi-San’s cultural and spiritual identity. This land was among the first to be seized by European settlers during colonization, and for the Khoi-San, it symbolizes a direct link to their past. The occupation is not only a demand for restitution but also an assertion of sovereignty.The enduring legacy of colonialism and apartheid remains deeply woven into South Africa’s social fabric, with systemic injustices continuing to cast long shadows. These challenges have significantly tested the ANC (African National Congress) government. In fact, after three decades of unbroken political dominance, Nelson Mandela’s iconic party has lost its outright majority, entering a new era of coalition politics that will certainly redefine the trajectory of the land of plurals.