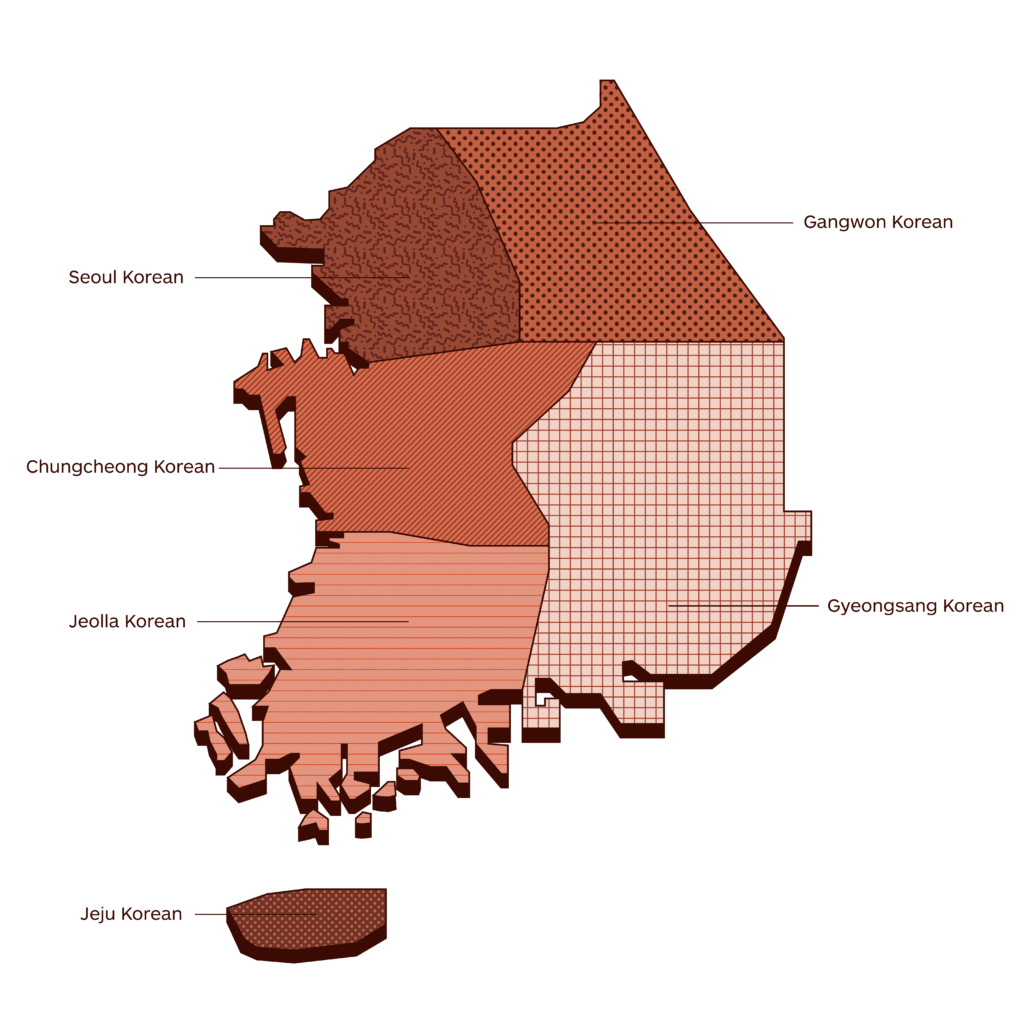

Language

Legend

-

Seoul Korean

-

Gangwon Korean

-

Chungcheong Korean

-

Jeolla Korean

-

Gyeongsang Korean

-

Jeju Korean

The Standard Korean spoken in both the North and South originates from the Seoul dialect but for political reasons, the Korean language has developed very differently in each country.

The South allied with the United States during the Korean War (1950-1953), and as a result American English began to influence the language. In addition, South Korea remains open to Western influence and enforces compulsory English education, resulting in rapid linguistic change.

In contrast, North Korea allied with the Soviet Union during the Korean War, resulting in the borrowing of Russian lexicon. After the war, North Korea’s extreme political isolation stalled or completely halted any language change. The North Korean government opposes all Western influence, including English.

The language spoken in the North and South has deviated drastically in the relatively short time since the war; as a result, North Korean defectors struggle to understand the Korean spoken in the South.

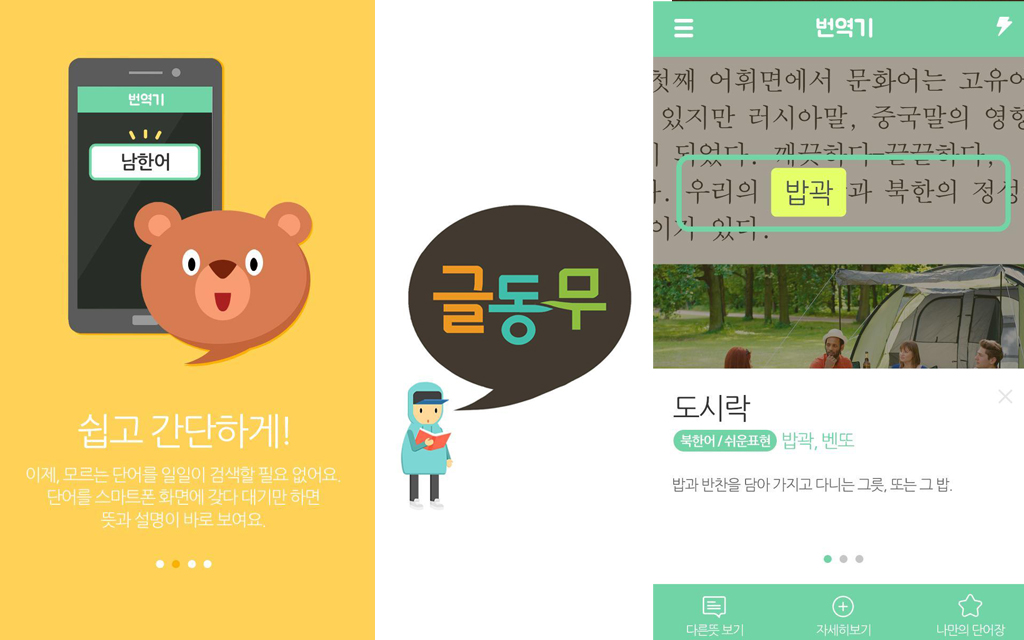

The cell phone app, Univoca, was created to help North Koreans translate unfamiliar Southern terms into their Northern equivalents. Specifically, its purpose is to support North Korean defector students who are struggling with the language barrier in schools.

As the Korean language in both regions isn’t the same dialect, it is not surprising that there are also some differences when it comes to pronunciation in the spoken words: some vowels with consonants are not pronounced the same in the different regions, some letters might be completely ignored when the residents of either South or North Korea pronounce the words. There is also evidence present that the North Korean language’s pitch is not quite the same as in South Korea. A few Chinese characters are also used in Korean and are referred to as “hanja.” These characters are commonly pronounced a certain way in South Korean and in another in North Korean. On occasions, they can even be found written differently.

The first key difference is in the South Korean language, where the formal name used for the language spoken by its citizens is Hangugeo. In North Korea, it’s called Chosŏnŏ.

In North Korea, thousands of words have been coined to express socialist ideas and systems; difficult Chinese loanwords have been nativized; expressions pertaining to feudal society and ideology have been eliminated from the newly compiled dictionaries. All these new words, and many common words that have undergone semantic change, may obstruct mutual understanding between the speakers of Korean in the North and South of the peninsula.

In 1966, Kim Il Sung made the following statement in defence of North Korea’s standard language, mwunhwae: “Firmly rooted in the rotten feudal, bourgeois life, the Korean language now spoken in Seoul still uses the type of nasal twangs favoured by women to flirt with men …”. This was a kind of official declaration of the linguistic divergence of North Korea from the South. Mwunhwae, ‘cultured language’, which is spoken in the North as the standard version of speech in Pyongyang, is quite different from the traditional phyocwune ‘standard language’, which refers to the speech favoured by southerners as the official standard language in Seoul.

The North Korean government at first implemented a policy aimed at the total eradication of illiteracy in North Korea. They claimed that this was achieved by the beginning of 1949 (Kim chin-wu 1978b; Kumatani 1990). If it was true, it was a remarkable achievement, considering that South Korea still recorded an illiteracy rate of 8.3 per cent in 1958. Such eradication could not be achieved in a short period of time if people had to learn how to read and write Chinese characters. So Chinese characters were rapidly removed from textbooks, and many literary works using exclusively hangul were published. Thus, the first stage of North Korean linguistic policy can be called a period of ‘democratization’ because it gave people access to written information and education. In fact, in North Korea, literacy was an essential prerequisite to making people understand and accept the new ideology. The main purpose of linguistic policy in its first stage was, therefore, to enable the party and the government to spread their ideological policies among the people. The next step was the “nativization” of the language in North Korea. ‘Koreanization’ of vocabulary was the main issue after the abolition of Chinese characters. Sino-Korean and foreign words were discarded and replaced by native Korean translations or coinages such as: kwancel > ppyemati (‘bone joint’) chuswu (‘harvest’) > kaulketi (‘autumn collection’) salkyun (‘sterilisation’) > kyun-cwukiki (‘germ killing’) phama > pokkummeli (‘broiled hair’) tatami > nwupi-toscali (‘quilted mat’). However, it is not true that Sino-Korean words have almost disappeared in North Korea, and the extent of the success of North Korea’s language policy on nativization is open to doubt.

With regard to orthography, Kim Il Sung in his speech of 3 January 1964 suspended reform in that area. Instead, he called for the abolition of ‘undesirable’ words and the arbitrary or ‘revolutionary’ use of ‘desirable words’. This started the period which many scholars called ‘prescriptivism’. As a result, new dictionaries were compiled: the Cosen Mwunhwae Sacen in 1973 and the Hyuntay Cosenmal Sacen in 1981. In the latter, some newly coined words were added, while certain anti-revolutionary definitions were purposely omitted. Henceforth, language was utilized more and more for political purposes. In his 1966 speech, Kim insisted that language ‘is a strong weapon for the realisation of revolution’.

Linguistic differences between North and South Korean

Alphabetical order

Most people would be surprised to find that the alphabetical order in a dictionary is different. In a North Korean dictionary, for example, words beginning with ‘o’ come after consonants, namely after hiuh, because ‘o’ is considered not a consonant, but a mute symbol.

Vocabulary

The field of vocabulary shows probably the most serious divergences. Abolition of many Sino-Korean words, standardization of words originating in northern dialects and archaic words or the coining of new words during the so-called mal tatumki wuntong (language purification movement) have been mentioned earlier.

Phonetics and phonology

Phonetic and phonological differences are apparent but do not prevent speakers of North and South Korean from understanding each other.There are some well-known phonetic and phonological features in which North Korean differs from Seoul standard speech.

Syntax and morphology

- The plural concept, expressed formally by -tul, is used much more frequently in the North

- Verbal clause structure is preferred to nominal phrases, if they are interchangeable, especially when used as the title of newspaper articles, etc. It is in complete contrast to the usage in South Korea, where a nominal phrase is more often used. This is presumably due to North Korean reluctance to use Sino-Korean words. Whereas Sino-Korean words allow the concise nominal expression, North Korean has to depend on verbal phrases to express the same message, using a pure Korean verb

- In North Korean, the prospective modifier is used when the present modifier would be used in South Korean

In North Korean, style, as a powerful weapon for revolution, is regarded as one of the most important elements in carrying out the social function of language. Kim Il Sung claimed that the stylistic characteristics of cultured language must reflect the needs of the working class.

The characteristics of North Korean stylistics are: a preference for short sentences to express militant emotion; preferences for a style embodying commands and exclamation, and for an emphatic style achieved through use of repetition; the use of a verbal clause rather than a nominal clause in a title; and a preference for spoken style overwritten style.

Crossing Divides: Two Koreas divided by a fractured language. BBC.

Photo credit: Mark De Jong, Unsplash