Localization

Vivekanand Pani

Co-founder, Reverie Language Technologies

Vivek is the Co-Founder and CTO of Reverie Language Technologies, a company specializing in text and speech technologies for Indian languages. With more than 20 years of experience in Indian Language Computing, Vivek is one of the very few subject matter experts who are passionate and dedicated to making usage of Indian languages easy on digital platforms. Vivek began his Indian language journey at the Center for Development of Advanced Computing (CDAC), Pune, in the year 1997. His journey spans across developing advanced multilingual tools for early computing devices and word processing software for computers to leading today’s state of the art AI-driven Indian language technologies like Automated Speech Recognition, Machine Translation, Text-to-Speech, Natural language.

A sub-continent growing rapidly in the digital world, with a need to access content in all its native languages: what does it mean to localize for the Indian market?

Imminent discusses the history and future of localization in India with Vivekananda Pani, the founder and CTO of Reverie Languages, a Bengaluru-based company that supports businesses with solutions for growth in the Indian languages.

In conversation with Pani is Gaia Celeste, a Senior Community Manager at Translated, where she is responsible for scouting talent from all over the world and supporting people in translating at their best.

Pani and Celeste’s conversation paints an all-round portrait of the localization industry in India. On the one hand, Pani illustrates his views on localization technology, from the accuracy of translation memories to keyboard support for Indian alphabets. On the other, people are at the heart of this rich mosaic, as Pani and Celeste discuss recruiting translators in India, multilingualism, and the historical roots of how Indians went from using English as a business language to the booming demand for localized content.

If you want to know more about India…

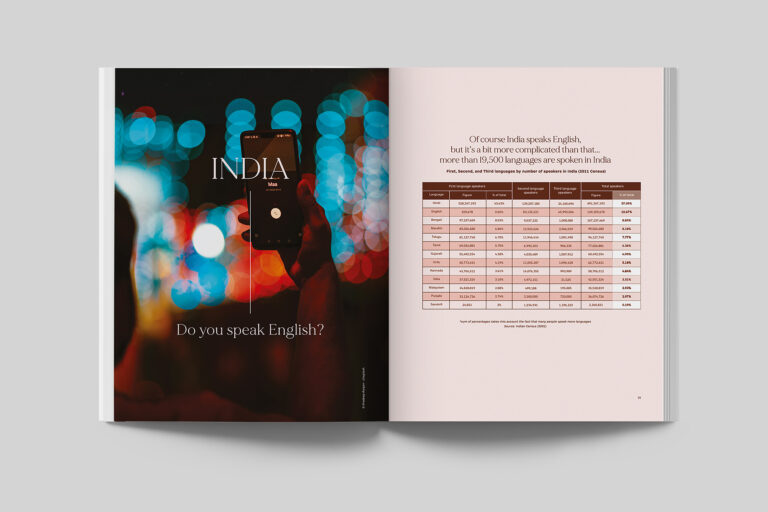

India, do you speak English?

How relevant can English-only content be in a multilingual India?

Multi-awarded author and journalist Luca de Biase is a professor at Pisa University, innovation editor at Sole 24Ore newspaper and a Member of the Mission Assembly for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities, amongst many other roles and achievements.

The article of Luca De Biase

Understanding India

Language Data Factbook

To which language should you translate to localize in India? The Imminent collection of linguistic, demographic, economic, social and cultural data.

Discover moreInterview questions and answers

What is the history of Reverie Languages?

I got into language computing for Indian languages quite early on, in the mid-90s. We were looking at a country, India, that was growing phenomenally in the digital market. It was a point in time where phones were only just entering the lives of Indian people, in a country that has now moved to 5G technology. We were right on time to interpret this need for technology.

You are also meeting the needs of Indian people to access content in their languages. What is the relationship between languages in India, particularly with English?

Nearly 80% of Indian people are literate, but of these people, only 10% are comfortable with English. This means there are significantly more Indian-language users than English-language users.

What about business? Would this still be conducted in Indian languages?

Since India got independence, most higher studies have been in English. The only university courses that are not in English are Literature programs in Indian languages. So, for example, you can have an MA in Telugu, but you can’t study Economics in it. This means that people starting a business have background training in English, although I’m not ruling out that they may be using their native languages to do business. Considering that over 70% of the population is not literate in English, while it is reasonable to assume that B2B conversations will take place in English, B2C is most likely happening in local languages.

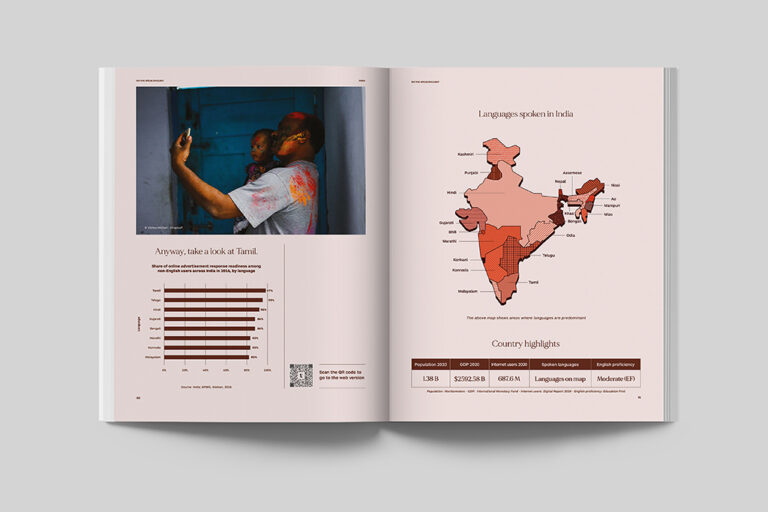

At Translated, we see many international companies that are rapidly growing in the Indian market, and localization in different Indian locales for B2C communication is also growing. Hindi is our biggest locale, but we are noticing a growing demand for other Indian languages too. Which languages do you think have grown the most in the last ten years?

Hindi is the most popular language and is predominant from several points of view. I wouldn’t agree that the other languages are as low as projected by the stats, though. There’s a reason for it. The Internet came to India in English back in 1995. Hindi was the first supported language, 15 years later. Other languages took even longer. This means that the amount of data we see is tied to the time people have had to use localized content, and for that content to breed and grow.

You mentioned the difference caused by education. Do you see any other contributing factors related to culture and identity?

Absolutely. Let’s take the example of e-commerce. The international icon for the “basket” is the shopping cart. However, carts only arrived in India a couple of years ago. People shopped using bags. The shopping cart reference is completely alien to them.

Do you see a rise in foreign words being adopted in Indian termbases and vocabularies?

Before motorcycles were invented, we used horse-drawn carriages. Now, the term for carriage would work with any type of moving vehicle. “Motor”, however, was introduced when motor cars arrived in India. It was called “motor”, and Indians adopted it as it was. This logic also applies to new technologies, like phones. I believe that do-not-translate words are important to guarantee the uniformity of access to new technology. While no one would look for another word to describe a staple food like “rice”, terms related to mobile technology and new living habits are evolving rapidly.

Would the words retained as-is be transliterated in the Indian languages?

Yes – when you don’t translate, you transliterate. The good thing about Indian languages is that our scripts are phonetic, so we can write everything we pronounce. This is how we create new words.

It looks like there’s a growing corpus of terms that you are importing into Indian memories and that is influencing machine translation. Where do you see MT going in the Indian market?

Machine translation is growing everywhere. Websites 15-20 years ago would often show text that would stay as it was for months. Now websites are much more dynamic. I’m not just talking about e-commerce – all websites want to stay relevant and up to date. It would be impossible to keep pace with this growing demand without MT. So I would say that, because there’s a growing demand for content – by which I mean localized content of good quality – MT and term banks are growing alongside it. It works both ways.

Do you see any other trends, for example, related to video?

Video is a lot easier and a lot more engaging for users. It has the power to explain more with fewer words. At the same time, Indians specifically struggle with typing. This makes it natural for them to attempt to speak to devices. Engagement through voice and video has therefore grown phenomenally in India. I would still say that Indians are also happy to read and react to the written word.

It is very exciting to see how localization is not only opening up content to new languages but is also making it much more accessible through voice and video.

Do you have any fun facts about how other companies and markets see India?

Since you work with so many languages, what do you think is unique about India?

I’m coming from a Community Management perspective, which means scouting talents and giving them the conditions to translate at their best. These days, we’re noticing both a growing demand for Indian localization and a growing offering of highly specialized professionals who translate in Indian languages. One big difference for us is related to multilingualism. Indian translators come to us offering a portfolio of at least two or three target languages. We are used to other languages (e.g. European ones) where translators usually work in only one target, their active native language. How do you see this phenomenon from your insider perspective?

Most Indians, particularly from the non-Hindi-speaking areas, would speak at least two or three languages fluently. In some cases, fluency would also be reflected in literacy. What you are saying reflects the fact that in India, multilingualism is the norm.

Do you foresee any other trends related to technology?

For Reverie, it’s all about developing technologies to support localization. As you know, all memories and MT are based on data. For Indian languages, we have a scarcity of quality data. Data may be ambiguous, particularly from a spelling standpoint. In these cases, MT will be affected by noise and will learn slower. I wonder if this is only true for Indian languages, or also for other locales?

When it comes to glossaries and termbases for long-term projects that require the work of large teams, we tend to have a harder time with Indian languages, precisely because of the abundance of different spellings and synonyms, and the different regional inflexions. Where specific terms are ambiguous and our memories end up inconsistent, we put the whole team in a (virtual) room and have them align on one version. This is pivotal for reducing noise in the final user experience. At the same time, we also cherish the richness of language: while consistency is very important, texts must sound natural and reflect all the different nuances of the living language.

A good piece of learning for me as well, thank you!

Interview script

Gaia Celeste

Welcome everyone, this is a new Imminent Interview. Today we have with us Vivekananda Pani from Reverie Language Technologies localization company in India. We’ll be talking about machine translation technology and first and foremost the localization markets in India.

My name is Gaia and I’m one of the community managers at Translated. I will be in this interesting and exciting conversation with Vivek. I cannot wait. To jump into our conversation, I wanted to ask you Vivek if you could guide us through the history of Reverie, why you started the company, what was the need behind founding Reverie.

Vivekananda Pani

Just a minor correction: we are a language technologies company,and it becomes our natural responsibility to help the language use and localization industry with technology.

The history to this is actually very interesting. I got into language computing for Indian languages in the mid-1990’s. That’s really early.I got to work on the Indian language computing technologies for quite a bit and gained a lot of expertise on that. Since that was a strength and I had a good, deep understanding of the industry, the market needs and all. What we were looking at is, an India, that was just about to grow phenomenally in its digital, I would say, penetration.

The phones, when we started, which was not yet the active internet device was still reaching out to many people. The 2G network, although very poor at point in time, but had already got a good amount of emphasis on growing the network which, today as we speak, has now moved to 5G, and we have got pervasive internet connection everywhere. So understanding that we were actually at a point where that growth is likely to happen, we thought that it would be pertinent to work on Indian language technologies ahead of time right now but, you know, so that we are right on time when it is needed.

Gaia Celeste

Thank you so much. This is really interesting. Am I correct in understanding that basically we’re looking at a conjuncture in a market where technology is growing fast at that moment in time and you’re also sort of in matching a need of people to be speaking in their own languages? I could see from the website of Reverie that on the homepage it clearly states that you are matching this need of 68% of people in India who are looking into reading content in their own native languages.

How does that work? What’s the relationship between languages and English, for example, in India?

Vivekananda Pani

Literacy in our country is about 78%, let’s say nearly 80%, which is quite a large number considering 130 billion people. But out of these 80% of people less than 10% of English literate I would say when they can actually read English, understand, and use it easily. All the others who are literate in their native languages, they are comfortable in using. So they are able to use their languages more comfortably. I think that makes the Indian language usage or the Indian language users a significantly larger number of people.

When we say that we are trying to address this mass that is actually trying to address at least 10 times as many people who know English in our country.

Gaia Celeste

I see. And what about business? Do you see any difference between, for example, how people interact with apps in their daily lives and how people speak when they have to do business?

What’s the language for business in India?

Vivekananda Pani

This is a very interesting question. I would not be able to give you a very short answer to this.

I’ll have to give you a little bit of a background as well. See, from the time that India got independence our own education system that has been adopted in our country mandates that professional education is available only in English. If you are studying something that is not in English, you are most likely studying only literature. For example, if I want to study in Telugu, I can become an M.A. Master in Arts in Telugu only.That means I become a Telugu language expert.I can become a Doctor who knows Telugu.

By that, it basically,, I would say, it just sticks in an official way that the language of trade and business or official use will have to be English or will actually become predominantly English, although I’m not ruling out that businesses do not use local languages because, ultimately, even after all of this mandate the number of people who graduate and get into professional services is minimal.

That’s true all over the world. It’s not only in India. We still have, therefore, out of these 80% literate people more than 70% of people who would not understand English. So the businesses and the government actually do use the local non-English languages to communicate with people, to consumers, to users. Whereas when it comes to inter-business trade you would know that one professional with another professional can speak in English because if you have taken a professional study. Then it is given that you have studied English and that’s why you were there. I think at a business-to-business level, the communication can happen in English. But when it comes anything to do with consumers, in most cases, they do adopt local languages.

Gaia Celeste

That’s really very interesting. We’re seeing this, for example, as a localization company happening a lot of with different multinationals that are active in the Indian market. Whenever we deep dive into B2C, so into companies that are looking at communication with consumers, we do see this growing trend of a big request, a big demand for localizing into different Indian languages. We definitely started off with Hindi. This was for sure the first Indian language, for example, I came across as a community manager. But we’re seeing a growing trend for other languages as well. What is your take?

Which languages do you see having grown the most in the Internet demand for localized content in Indian languages in the last 10 years?

Vivekananda Pani

I would also agree with you that Hindi has been the most used language, and it is also in terms of the number of speakers it is the predominant Indian language. But I would also not agree that other languages are as low as it has been projected by a lot of statistics that have been – or even research that has actually found that out.

There is a reason to it. The Internet came to India in the year 1995. Hindi may have been the first language that got supported on any operating system for India and that did not happen until the year 2005 at least or maybe 2010. There was probably no Indian language that could have been represented on the Internet 15 years after the Internet came to India. The first language that still got supported was Hindi. Other languages have taken even longer time.

I would say let’s take my mother tongue: Oriya. That probably got supported on any of the popular devices’ operating systems maybe 3 or 4 years ago. So the fact is that the amount of data that you see is also paramount into the amount of time people have got to use it.

A user not only needs facilitation but also takes time to mature and start using a particular medium. We have number that are not telling us the truth because there is a history that has not actually supported the truth. Even then, in absolute numbers, Hindi is top. The least used official Indian language might actually still be matching up with English in terms of the number of fluent users.

Gaia Celeste

Thank you so much for the insight. And thinking about reasons why people are looking for localized content, you mentioned the fact that there’s definitely a relationship with education. You see a difference between how consumers speak and browse for content and how businesses speak with one another. But do you think there are any other components, for example, cultural aspects?

Are people looking into content in their own languages to reflect their cultural identity?

Vivekananda Pani

Of course, it’s not just related to the language. It is also what you are saying or how you depict certain things not only probably in the language but also in terms of visuals and icons and so on and so forth.

Let me take an example. When we are in e-commerce the common thing that we would see is the basket, right? At the time of checkout you would probably look at your basket. Whereas basket, or the cart, which has been the symbol of depiction across all e-commerce websites is actually alien to an Indian buyer.

Here in India, the supermarkets getting carts is a very recent phenomenon. People were used to actually carrying bags and bringing stuff in the bags.The icon of the cart or the term “shopping cart” and the localization of those they are culturally not fitting and, similarly, there are a lot of things even payments. Payments, customer support. Many other aspects are I would say it depends on the kind of business and service. Most of the terms that people are familiar with in English which have been borrowed from existing services in the West were not familiar to the Indians. They would be alien.

So yeah, I think it does make a big difference.

Gaia Celeste

I can definitely see that. Are there many terms, for example, that you keep adopted?

To make an example for you, we have a similar trend for Italian. We have so many terms that we have adopted from English, so many terms that we do not translate and are different from other, for example, European languages, where all terms are always translated.

Do you see a trend, for example, for part of the term basis for part of the glossary related, let’s say, to technology or to online shopping that you keep unlocalized that you keep in English or do you think that people are looking for all of the content to be properly localized and to be relevant to their culture.

Vivekananda Pani

Very interesting question. Let’s go back in time and say that the motor car was just about invented. Before that you had horse carriages. So in both cases, the word “car” is basically the short form of “carriage”. Therefore, even the horse carriages can still be called “horse car”. But when you introduce a motor car, the term “motor” becomes new. And when it becomes new and it is introduced to people, they will be able to relate to the new with the new word “motor”, and it is OK. Because that thing never existed before and since it didn’t exist before, it didn’t have a word. So when they see it for the first time and would like to know what it is called and if it is called “motor”, they’re OK. They’re associated with that. In that sense, I would say do not translate or retain it as is. Are the things that must be done to a lot of things that are new?

And I would agree that there are plenty of things that whether we call them new or not because they’ve been here for a long time now. But for a language it may still be new. For example, a mobile phone.A mobile is a mobile or maybe a cell phone. That is what they would call it, but there is no other local word in India in any Indian language for a cell phone. So I think yes, do not translate or retain as is. It must be done so that people are able to associate with a lot of new developments and new things or terminologies and terms uniformly so that they can also understand those across languages uniformly.

They can also search and find those uniformly. These are very important. Only the things that they are already familiar with. So you don’t want to introduce a new word for “rice” in Indian languages. Or you would not want to call “rice” as “rice” because that’s a staple food. That way, you would want to translate what people know and are familiar with very much. But you would actually not try and introduce new words in local languages and confuse people.

Gaia Celeste

Yeah let’s imagine someone coming to Italy and trying to rename pasta.

Vivekananda Pani

Oh yeah.

Gaia Celeste

We would never accept this.

Vivekananda Pani

You’re right, of course. And the whole world has accepted the word “pasta”. I don’t have a different word in Hindi for that. And I love pasta.

Gaia Celeste

Everybody loves pasta! In the most international language, there is food, right?

Vivekananda Pani

Right, right.

Gaia Celeste

Do you transliterate it, out of curiosity? Are any of the non-Indian words transliterated in Indian languages?

Vivekananda Pani

Oh yes. When you don’t translate, you transliterate because not everyone can read English. And if they cannot read English, they will still have to read the words that are not translated and, therefore, you represent. The good thing about Indian scripts and languages is that our scripts are phonetic.

You basically write whatever that you write whether it means something or it doesn’t mean something it can still be pronounced. Because every letter basically is a phonetic representation. So you basically, phonetically write a sequence, whatever you pronounce you can write that. People can speak and then associate. That becomes a new word so transliterate.

Gaia Celeste

Can you imagine from everything that you’ve been telling us that there is a growing corpus of terminology and of segments that are being put out there in CAT tools and all of the different systems that we use in the industry to generate localized content. Coming from an experience with machine translation, as you told us, Reverie was born with an eye for technology.

What do you think about the growing corpus of terminology that is currently influencing machine translation? Where do you see machine translation going for the Indian market?

Vivekananda Pani

Machine translation is becoming a very big need anyway. Let’s look at a website 15 years ago, or maybe 20 years ago.People used to develop websites and keep it like that. Our website will probably not need to be changed for months together. Today, you do not have a website that is not likely to change everyday. I’m not saying that it has to be an e-commerce website which is listing products everyday. Any website is trying to put in what is happening, what is new, what are the updates. That is a lot of dynamism in almost every business, every representation.

At the rate in which content is changing, and if one would like those to be represented in multiple languages, so that readership is wider. It’s going to be humanly impossible to continue having localizations by manual translations or not use a lot of automation or machine assisting all of that. Considering that these demands have been increasing and like you mention, the terminology is yes. The terminology banks are increasing. But the terminology banks are also increasing because we need to represent a large amount of knowledge in so many languages.

If something doesn’t need to be translated into any other language, then there is no point in having that terminology in any bank. Because that need is there, I would say that the translation corpus volumes are also increasing alongside the term banks. Which is what is actually helping the machine translation tools to be able to learn and produce much better and contextually qualitative translations.

Gaia Celeste

That absolutely makes sense. It’s a trend that we are seeing across different markets. The Indian market, of course, as you mentioned is booming right now. Do you see any other trends related to localization technologies? I’m thinking of, for example, text-to-speech or any other services that are related with videos and audios and other ways of people to connect with international realities through their phones, basically, and through the Internet.

Vivekananda Pani

Yes, I think one of the things is people are obviously connecting with videos a lot. That is because video becomes easier and a more interesting way of engaging a user. It also has the power to explain a lot more in fewer words if it is assisted along with visuals and so on. But at the same time, India specifically, or the Indian languages do face certain other problems.Indians continue to struggle with typing. Because they struggle with typing, it becomes natural for them to attempt speaking to a system. Typing in Indian languages by default, for most users, they find it a little more difficult so they would rather like to speak. Therefore, I think engagement through voice and video has actually grown phenomenally in India. However, I would still say that people love to read a lot. At least, because they don’t have to type but, let’s say, if they have made the queries If they get responses not necessarily in video but also in text, they’re happy to read.

Gaia Celeste

That absolutely makes sense.I can see myself a lot into what you just said. I do think as sort of coming to a close of this very interesting conversation that we had about localization that it’s really exciting to see how localization is not only opening new opportunities for people speaking different languages and being comfortable with their own languages but also being more inclusive in terms of different devices and platforms where content can be spread. Because exactly what you just mentioned, people who keep loving reading, they will be able to read content in a localized version but we’re also going towards a world where audio content is being put at the disposal of people who prefer or need to use that channel. Same thing goes for video content so that’s definitely an enthusing challenge for everyone in this industry for the future. Vivek, I want to thank you very much, but I also know that you do have some questions for us. I wanted to give you the opportunity to bring your own questions to this conversation.

Vivekananda Pani

Sure, one thing is that since you deal with so many languages and so many geographies of the world, I do have a few questions for you. One of them would be: How do you see India? Because when you compare India with other geographies and other languages, what do you think is unique to India in the first place?

Gaia Celeste

That’s a very interesting question. I’m coming from the perspective of someone working in community management.So what I do for a living is finding people and making sure that they can translate at their very best.What you were describing is really resonating in the experiences and lives of so many Indian translators that I’ve crossed paths with during the last couple of years. What we’re seeing as a trend is, of course, the growing demand for international companies to localize content into Indian languages.

For this reason, we also see a growing offer of translation services by Indian translators and by Indian companies. One big difference for us in our model is that, for example, at Translated, we usually only allow translators to translate into their active native language. For our traditional models, for example, if we take the European languages it usually means just one language. For example, I’m Italian. I speak Italian, I could only translate into Italian. For Indian translators, we do see a trend of people presenting their curriculum, their résumés and telling us that they are native and fluent in more than one language. And the level of their fluency is the same across the different languages we are really looking at bilingualism in a different way than compared to other realities, for example, the European one.

How do you see this from an inside perspective? Is this something that you also see in India? Or what’s your take on bilingualism?

Vivekananda Pani

Yes, of course. Most Indians, I would say, especially the non-English speaking regions, you would see almost everyone would be able to speak at least 3 languages. And they would be speaking 3 languages fluently, like their mother tongue. Sometimes people may not read as many scripts, but many times they would also be fluent even in reading and writing in more than 2 or 3 languages. So yeah, I think what you’re saying is something that is very common in India. We see that a lot.

Gaia Celeste

Thank you, thank you very much. I think we’re coming to a close. Unless you do have any other questions or things, topics that you want to share with us, of course.

Vivekananda Pani

There is one more question that I had, but that is more technical on this.

Gaia Celeste

Sure.

Vivekananda Pani

Since we work as a language technology company, for us, it’s about developing technologies that can help the localization industry, the translation industry and the language use industry for Indian languages. Now in that, as you would know that a lot of machine learning and NLP is being used, which is data dependent, data heavy .Like I said, the availability of data for Indian languages is not as rich. What we observed is that it’s not just that the availability is poor but it’s also the quality of data that is available that is also not very good. When I say that quality is not very good, sometimes it’s the data that is available, but the data is ambiguous that in a large amount of text if a particular word that is spelled in 5 different ways because it can still look the same this is something that is very typical to Indian languages.

In that case, the machine learning algorithms will actually consider those as 5 different words, and therefore, will not be able to learn anything properly about any of those words. Our work requires significantly large amount of variations in data and quantity of data to be able to learn the same. Do you also face the same kind of issues?

This, in my guess, should be common to the entire industry and which would that mean that it would continue to actually limp the Indian language translation industry.

Gaia Celeste

I definitely see this as a trend. What we’re seeing in terms of quality, for example, for many of our enterprise clients, which are the ones that most consistently translate into Indian languages. Is that we have, if compared to, for example, European languages, more of a hard time sometimes defining glossaries and style guides. Because as you mentioned, we know that many terms can be spelled in different ways. For example, brand names can be spelled using the English alphabet or can be spelled using the transliterated Indian relevant alphabet. So that’s definitely a big challenge that we are facing.

In our work, for example, when we came across these issues, one aspect that really helped us is putting people together. We tend, as an industry, to think about the work of translators as very isolating, translators are usually considered as lone wolves. But a big trend in the industry is working together. If we take long-term continuous localization projects, for example, for app, where, as you mentioned, content online can be updated everyday if not multiple times a day. We usually have big teams of translators working together.

Whenever we come across these instances where we have ambiguous terminology, we try and put everyone together in a room, well, a virtual room, like a Zoom meeting and have them brainstorm together and come across one solution. And then ask everyone to stick to that solution. This is, of course, not always possible, and it’s also not always in our aims. Meaning, if we are localizing for a website, at least this is my take, some terms have to be consistent. So if we choose, for example, to call a “cart” a “shopping bag” this should always be called a “shopping bag”. But in text, we’re also looking at something natural and really writing or speaking as someone would in that specific language.

Maybe it’s not it’s not a blunt answer or it’s not a blunt take, but I would definitely say glossaries and coming to communal choices within a team of translators really helps us out. Nailing down style guides really helps us in this case to make machine translation and suggestions more consistent.But we’re also looking for that richness, right? We’re looking for vocabularies to keep being that fluent and that flourishing with different nuances. Right.

Vivekananda Pani

Great, so that’s a good piece of learning for me as well, so thank you.

Gaia Celeste

That’s mutual, definitely, I want to thank you again so much for this interesting conversation and also thank everyone who has been listening to us. We will come soon with another episode of our interviews for Imminent. As you know, we are a research platform so we really have an eye for the future and can’t wait to see where machine translation brings us and where the different markets bring us in the near future.

Thank you so much, Vivek.

Vivekananda Pani

Thank you, thank you.

Gaia Celeste

Bye.

Vivekananda Pani

Bye.