Global Perspectives

December 2024

Key Statistics

- New Zealand is the world’s leading exporter of kiwis, accounting for 48.4% of the global market (OEC).

- New Zealand ranks 10th in the overall Prosperity Index in 2023 (Legatum Prosperity Index).

- With a score of 77.8, New Zealand’s economic freedom ranks 6th in the 2024 Index of Economic Freedom (The Heritage Foundation).

- Auckland was ranked the most liveable city in 2021 (Economist Intelligence Unit).

- New Zealand is the largest milk exporter globally, with an export value of $6.8 billion in 2023-24 (ExportImportData).

Aotearoa – Land of the Long White Cloud

In 2021, Tē Pāti Māori, New Zealand’s Māori Party, gathered over 70,000 signatures within days for a bold proposal: renaming the country from New Zealand to Aotearoa. The English name, laden with colonial history, is seen by many in the indigenous community as a lingering wound. Yet the now-common name is only the latest in a long and complex story. In 1640, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman named the territory Nieuw Zeeland, inspired by the province of Zeeland in the Netherlands. Over a century later, as the British arrived, James Cook mapped the islands and transformed the name into New Zealand. So why change it now, over three centuries later?

The answer lies in the power of words. New Zealand says little about the true soul of these islands. Before the Europeans, it was the Polynesians – now known as Māori – who colonized the archipelago, giving it the poetic name Aotearoa, meaning “land of the long white cloud.” This name, rich in mythology and symbolism, reverberates with oral history: it is said that, in the 1300s, Polynesian voyagers were guided to the islands by a long white cloud visible during the day and luminous at night. The legend of Kupe, one of the first navigators, recounts how his wife, Hine-te-aparangi, spotted the cloud and exclaimed, “He ao! He ao!” (“A cloud! A cloud!”). From that moment on, the land became known as Aotearoa, forging an inseparable link between the sky, the sea, and Māori culture.

The deeper meaning of the name, as with many indigenous words, is layered and defies simple translation. Aotearoa is composed of several elements: Aotea and roa, or Ao, tea, and roa. The word Aotea could refer to many symbolic elements, such as one of the canoes of the great Polynesian migration, the Magellanic Cloud visible near the star Canopus, or even a bird or food source. Ao can mean cloud, dawn, day, or world, while tea translates to white, bright, or clear. Roa adds the notion of length or height.

The arrival of the Māori was only the beginning. After them, the islands attracted migrants from every corner of the globe, becoming a melting pot of diversity. The indigenous population initially settled along the coasts because their culture was deeply tied to fishing and navigation. Over time, these settlements expanded inland, creating villages and small centers. The arrival of Europeans revolutionized the island’s demographic structure. Despite the islands not being a big attraction to Europeans – they were known as the last and loneliest spot on the globe due to their remote location – British settlers arrived en masse, followed by Scots, Irish, French, Germans, and Scandinavians, lured by assisted migration schemes promoting the settlement of workers and families. In addition, the 19th-century gold rush attracted Chinese, Australians, and Americans, while in more recent times, communities from the Middle East, Africa, and the Pacific Islands have enriched the country’s cultural fabric.

A significant demographic shift began in the 1950s with the arrival of Asian students seeking education and opportunities. This wave of migration marked the birth of urban centers like Auckland, now deeply intertwined with Asian migration. Today, 28% of Auckland’s population identifies as Asian, reflecting how this movement has reshaped New Zealand’s urban identity. This young, cosmopolitan population has added new layers to the country’s cultural mosaic, particularly in the North Island, the heart of its economic and demographic vitality. These dynamics underline New Zealand’s strategic role in the Pacific: a bridge between the Asian economies and the Western nations; a meeting point of ancient traditions and modern innovation.

Source: NZ Stats

Despite this remarkable diversity, New Zealand remains one of the least densely populated countries in the world, with just 20 inhabitants per square kilometer. It is a land where sheep far outnumber people, yet its urban population is concentrated primarily in the North Island, the economic hub of the country. From the coasts settled by early Polynesian fishermen to today’s modern cities, New Zealand has built its identity as a land of migration and opportunity. This mix of breathtaking landscapes and an incredibly varied human tapestry makes New Zealand – or Aotearoa – a contemporary symbol of cultural coexistence and resilience. The lingering question is: how much longer can a colonial name represent a country so deeply intertwined with its indigenous roots?

Toitū Te Tiriti – Respect the Treaty

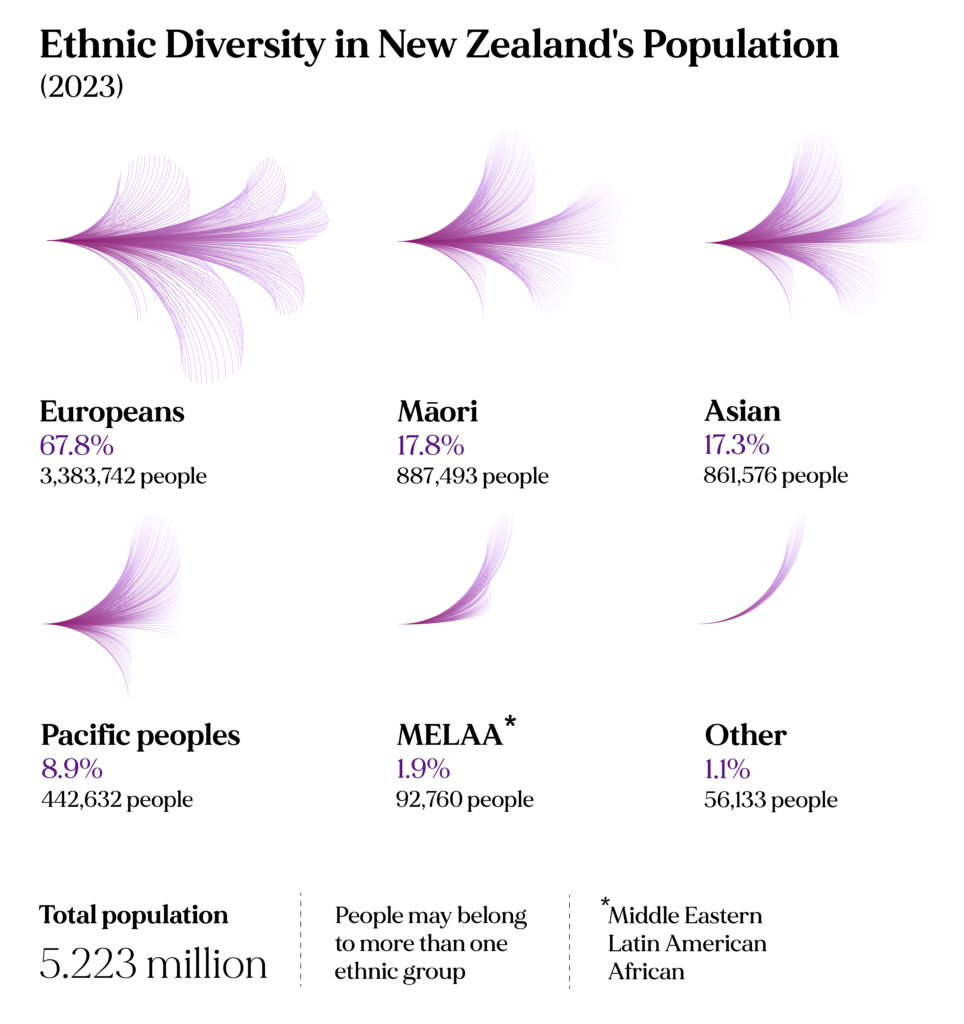

The Māori community holds a vital place in New Zealand, representing a vibrant cultural dimension that deeply influences the nation’s identity. As of 2023, Māori make up over 17% of the population (NZ Stats), and their contribution extends beyond culture to significant economic influence. Amid a period of broader economic uncertainty, the Māori economy is thriving, with an estimated value of $70 billion, projected to reach $100 billion by 2030 (RNZ). However, this flourishing sector, rooted in export-driven industries such as fishing, forestry, agriculture, and tourism, currently represents only 1.4% of New Zealand’s total GDP (NZ Herald). Challenges persist, including high exposure to international market fluctuations and limited access to entrepreneurial opportunities (Ministry of Māori Development).

Despite these constraints, the cultural and philosophical contributions of Māori extend far beyond mere numbers. For the Māori, neoliberal economic structures have historically undermined their social, economic, and political frameworks, eroding collective values. In contrast, Māori economic models prioritize relationships and reciprocity, fostering cycles of prosperity that look beyond short-term gains. This approach emphasizes shared values and collective aspirations, integrating distributive leadership to ensure intergenerational well-being.

The collective philosophy underpinning Māori life and the Māori economy is an invaluable asset for New Zealand, offering a blueprint for resilience and renewal. At its core lies a deep commitment to community, interconnectedness, and shared responsibilities – principles that could guide New Zealand toward a more inclusive and sustainable future.

A dictionary of Collectivism

Source: Humanex

The Māori language, te reo Māori, encapsulates profound meanings and concepts that reveal how deeply integrated and significant the community is within New Zealand. Yet this prominence was not always recognized. The early encounters between European colonizers, known as Pākehā, and the indigenous Māori were marked by conflict, pushing the Māori into a long period of marginalization and exclusion. This fraught relationship extended to te reo, which suffered suppression for decades. Speaking the language was actively discouraged; those who dared to use it were ostracized or even physically punished. As a result, just two generations ago, only a quarter of the Māori population could claim fluency, and by the 1970s, the language teetered on the brink of extinction.

At the heart of this linguistic suppression lies the Treaty of Waitangi, a pivotal document signed in 1840 that sought to regulate the relationship between Pākehā and Māori. While it recognized Māori ownership of their lands, it ceded sovereignty to the British Crown, embedding a framework of assimilation and subjugation. The treaty’s effects were deeply felt through policies like the Native Schools Act of 1867, which mandated English as the sole language of instruction, punishing those who spoke Māori. Education systems reinforced colonial dominance, sidelining indigenous knowledge and relegating Māori to the periphery of society.

Resistance began to take shape in the mid-20th century. As urbanization surged and global civil rights movements gained momentum, Māori activism found its voice through groups like Ngā Tamatoa (“The Young Warriors”). In the 1970s, these activists toured the country for two years, gathering signatures for a petition to introduce Māori language education in schools. Their efforts culminated in 1972 when the petition was presented to Parliament, and in 1987, te reo Māori was finally recognized as one of New Zealand’s official languages, alongside English and New Zealand Sign Language.

This victory paved the way for initiatives like the Kōhanga Reo (“language nests”), which redefined early childhood education by centering it around Māori cultural values and methods of knowledge sharing. These efforts reversed the decline of te reo, and by 2021, 7.9% of New Zealanders were fluent speakers, up from 6.1% in 2018 (NZ Stats). Additionally, over 30% reported having some understanding of the language (NZ Stats). While English remains the dominant language, it is increasingly infused with Māori words and phrases, reflecting the deepening cultural interconnection across the nation.

Challenges remain. Many Māori still report experiences of racism, and true equality has yet to be achieved. Nevertheless, the prominence of Māori culture today is undeniable. From street signs and advertisements to social media and the iconic haka performed by the national rugby team, Māori traditions are celebrated with pride. This resurgence underscores a growing recognition that the integration of indigenous communities transcends the Treaty of Waitangi. It is a collective identity project, a testament to how embracing diversity can transform a nation. In New Zealand, the Māori language and culture are not relics of the past – they are living, evolving elements of a shared future, making the country a powerful example of cultural enrichment through dialogue and mutual respect.

New Zealand

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Read it now!Kiwi – the Essence of the Island

Words shape our world, carrying meanings that are deeply rooted in history and culture. Depending on where you are, the same word might evoke entirely different concepts. This unique aspect of language is both a reflection of human empathy and a source of endless complexity. It captures the essence of who we are and where we come from.

One of the best examples of this is the word kiwi. This term, originating from te reo Māori, embodies New Zealand’s unique identity. Remarkably, it carries three distinct meanings that converge to tell the story of the nation. In New Zealand, kiwi can refer to a bird, a person, or a fruit, each representing a facet of the country’s cultural and economic identity.

Originally, kiwi referred to a small, flightless bird endemic to New Zealand. The name, derived from Proto-Polynesian roots, mimics the distinctive call of this nocturnal creature, making it a rare example of linguistic onomatopoeia immortalized in taxonomy. The kiwi bird is as peculiar as it is precious, with hair-like feathers, a long, slender beak, and a strongly territorial nature. Once abundant across New Zealand, the bird now teeters on the brink of extinction due to habitat loss, predation by introduced species, and other human-induced factors. Nevertheless, it remains an enduring symbol of New Zealand’s natural heritage, proudly adorning coins, stamps, and logos around the world.

But the story of the word kiwi doesn’t end with the bird. During World War I, New Zealand soldiers earned the nickname “Kiwis” from their Australian counterparts, a term that quickly gained traction. Over time, it became a fond moniker for the island’s inhabitants, a badge of honor that embodied the resilience, ingenuity, and distinct identity of New Zealanders.

And then there’s the kiwi fruit – the most globally recognized bearer of the name. The story of the kiwi fruit adds another layer to the term’s evolution. Originally called the Chinese gooseberry for its East Asian origins, the fruit was brought to New Zealand in the early 20th century. By the 1950s, growers sought to export it but felt its original name might hinder international appeal, especially during the Cold War. To strengthen its association with New Zealand, the fruit was rebranded as the kiwi fruit, recalling the country’s emblematic bird. The name proved a marketing triumph, positioning New Zealand as a global leader in kiwi fruit production.

Today, kiwi fruit is a cornerstone of New Zealand’s agricultural exports, accounting for 48.4% of the global market (OEC). Nearly 3,000 growers cultivate 13,600 productive hectares, producing around 184 million trays annually, primarily for export (NZ Horticulture Export Authority). While green kiwis have traditionally dominated the market – especially after surviving a bacterial disease outbreak in 2010 – the sweeter gold and red varieties are gaining popularity due to their higher market value. In 2024, gold kiwi exports generated 2.4 billion NZD, up 24% from the previous year, with China being the largest buyer (Stats NZ). The European Union comes next as a key market for both gold and green kiwis, alongside Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

New Zealand’s Top Export Markets, 2023

Source: OEC

However, kiwi fruit is just one piece of New Zealand’s agricultural success story. The country’s economy relies heavily on agriculture, a sector that has long been its backbone. It is a top global exporter of dairy products, beef, lamb, wool, fruits, vegetables, and wine. Dairy and meat exports alone make up about two-thirds of the nation’s agricultural revenue, employing over 78,000 people in rural areas as of 2023 (Statista). This industry also drives urban economies and secondary sectors, including renewable energy, showcasing the interconnected nature of New Zealand’s growth.

Agricultural innovation has been key to maintaining the sector’s global competitiveness. Farmers are increasingly adopting cutting-edge technologies to improve efficiency and reduce costs, such as electric vehicles and advanced mechanization. This shift aligns with New Zealand’s ambitious environmental goals, which aim for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions – excluding agricultural methane – by 2050. The adoption of sustainable practices reflects a broader transformation within the country, combining economic progress with environmental stewardship. The kiwi fruit, as humble as it may seem, represents much more than agricultural success. It is a symbol of New Zealand’s ability to blend tradition with modernity, ensuring its place in a rapidly evolving world. As the country continues to innovate, balancing its rich natural resources with sustainable practices, the story of the kiwi – in all its forms – serves as a reminder of New Zealand’s ability to adapt and innovate.

Ao Hangarau – World of Technology

In an economy grappling with a prolonged recession, New Zealand’s tech sector stands out as a beacon of growth, reflecting the innovation and resilience of its people. Globally recognized for its reliability and sustainability, the country’s advances in technology are bolstering its reputation. Through recent initiatives, the government has shown a strong focus on areas such as AI and e-commerce, which not only enhance the productivity of the tech sector but also stimulate the broader economy. Specifically, e-commerce is enabling local industries to access global markets once dominated by large corporations, accelerating their growth. At the same time, AI is proving transformative, boosting productivity and improving workplace safety.

Two standout initiatives are driving the adoption of AI across various sectors while aiming to make this technology integral to business operations. Launched this year, the AI Activator program supports small and medium enterprises (SMEs) by providing access to cutting-edge research, technical assistance, and a range of funding options. On another front, the GovGPT pilot program is streamlining access to government services through a multilingual chatbot, offering citizens accurate and accessible support.

This emphasis on technological innovation is no coincidence. In 2021, the tech sector contributed NZ$7 billion to the country’s GDP (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment). From 2016 to 2021, it grew steadily by 10.4% per year, significantly outpacing the broader economy’s annual growth of 5.1% (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment). By 2023, tech exports reached NZ$10.7 billion (NZ Tech), while offshore revenues climbed to NZ$13.52 billion (Business Desk NZ), positioning the industry as a key player in New Zealand’s economic landscape.

Technology’s potential goes beyond economic metrics. With minimal reliance on natural resources and no need for physical transportation, the sector offers more sustainable growth opportunities. It supports the country’s transition toward a high-income economy while aligning with its environmental objectives, such as achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

New Zealand’s tech sector encapsulates not just economic resilience but also the country’s innovative spirit, creating pathways for sustainable growth and global influence. Three compelling examples further highlight the sector’s value as a driver of preservation and economic growth.

New Zealand Tech Sector in Numbers, 2023

Source: NZ Tech

The Success of HealthTech Sector

New Zealand has long been a cradle of healthcare innovation, from co-discovering the structure of DNA to inventing the disposable syringe. Today, its HealthTech industry is at the forefront of global advances, combining cutting-edge technology with a deep commitment to improving lives. With exports exceeding NZ$2.6 billion annually (RNZ), this dynamic sector is reshaping healthcare delivery and creating solutions that matter.

Take Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, for example, whose respiratory systems help over 14 million people in 120 countries breathe easier each year. Or HealthPathways, a digital platform used by 60 healthcare systems worldwide to guide clinical decision-making for 35 million patients. In the United Kingdom, Kiwi ingenuity has become indispensable: companies like Cemplicity are reducing infection rates through data-driven patient feedback, while Toku Inc.’s AI-powered CLAiR platform assesses cardiovascular risks via retinal scans, tackling one of the world’s leading causes of mortality.

The partnership between New Zealand and the UK is a key driver of this success. With a robust free trade agreement in place, Kiwi companies are thriving in the UK’s healthcare ecosystem. Chiptech, a leader in digital healthcare alarms, supports over 130,000 digital connections in the UK, saving the healthcare and social care systems an estimated £580 million annually. Similarly, The Insides Company’s innovative devices for severe intestinal conditions are now used in more than 30 UK hospitals, making life-changing care more accessible.

What sets New Zealand apart is not just its technological prowess but also its focus on equity and inclusion. Emerging areas like AI diagnostics, regenerative medicine, and wearable tech are increasingly being co-designed with Māori and Pacific communities, ensuring that innovations address diverse cultural needs. This approach aligns with a growing global emphasis on equitable healthcare and positions New Zealand as a leader in “indigi-healthtech.”

Looking ahead, New Zealand’s HealthTech market is forecast to grow from NZ$268 million in 2024 to NZ$358 million by 2029 (HealthTech World). With its world-class universities, renowned for life sciences and medicine, and a legacy of excellence in biotech and clinical trials, the country is nurturing the next generation of healthcare innovators.However, despite its achievements, the sector faces challenges. Investment in New Zealand HealthTech remains relatively low compared to global peers, peaking at NZ$92 million in 2021 but declining to NZ$67 million in 2023. This funding gap particularly impacts early-stage startups, where the average seed investment is a modest NZ$1.2 million – far below the levels seen in countries like Ireland or the Netherlands (RNZ). Without increased capital support, the sector may struggle to maintain its momentum, threatening its potential for further innovation and growth.

SAM: Meet the World’s First AI Politician

In 2017, New Zealand’s tech sector introduced a groundbreaking political experiment with the creation of SAM (Semantic Analysis Machine), the world’s first virtual politician. Developed as part of a collaboration between Victoria University of Wellington, the tech company Touchtech, and entrepreneur Nick Gerritsen, SAM represents a shift toward technology-driven governance. SAM’s primary goal is to give a voice to New Zealanders by gathering public input and processing it into actionable political insights, sidestepping the often messy and biased nature of traditional politics.

SAM is powered by artificial intelligence, learning from vast amounts of data gathered through platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and direct surveys. This allows SAM to offer a more transparent and responsive form of representation, removing the personal biases of human politicians and focusing on public sentiment. Unlike traditional politicians, SAM is designed to listen without forgetting, ensuring that all opinions are considered in decision-making processes.

Since its launch, SAM has been processing thousands of messages every day, growing more intelligent as it interacts with the public. It aims to make political decisions based on facts and collective opinions, integrating advanced technologies like blockchain to potentially influence actual policy-making. This could create a new form of participatory democracy where citizens can directly impact political decisions, ensuring that public needs are met in real time.

However, the emergence of SAM raises significant questions about the role of AI in governance. While some view it as a more democratic and accountable form of political representation, others worry that AI systems might lack the emotional intelligence needed to navigate complex political issues. Additionally, there are concerns about how AI could be manipulated or how it might impact existing power structures.

Despite these challenges, SAM has garnered significant attention and interest within New Zealand and beyond. In 2018, it was showcased at the Digital 5 Summit, an event where the world’s leading digital nations discuss the future of technology and governance. Though SAM is still in its early stages, its development signals a potential shift toward more direct and technology-enhanced forms of democracy, driven by data and AI. Whether it will become a widespread model or remain a novel experiment remains to be seen, but its impact on the conversation around tech-driven politics is undeniable.

Saving Te Reo Māori

In New Zealand, the revival of te reo Māori, the country’s indigenous language, is incorporating modern technology in ways that bring ancient traditions into the digital age. Once silenced by colonial policies, te reo Māori is experiencing a renaissance, and technology is proving essential in this transformative journey.

Take the Kupu app, for example. This simple tool allows users to scan everyday items, such as a chocolate bar, and instantly translate the label into te reo Māori. As well as teaching vocabulary, the app is making the language part of daily life, seamlessly integrated into tasks we don’t typically associate with learning. It’s a testament to how technology can make an ancient language feel present, active, and relevant in today’s world.

Beyond apps, online platforms have opened the doors to te reo Māori classes, connecting learners from Auckland to Zurich. The Māori diaspora, as well as curious global citizens, can now participate in language lessons that were once confined to New Zealand. This global community of learners is not just preserving the language but actively participating in its resurgence. In a world where technology often disconnects, these platforms are doing the opposite – they’re bringing people together in the name of cultural and linguistic preservation.

Māori Television has also played a key role in the language revival, providing educational content that blends storytelling traditions with modern production techniques. Its shows bring te reo Māori to life in ways that resonate with both young viewers and older generations. The network is offering more than just lessons in language; it’s presenting Māori culture and history through a contemporary lens, demonstrating that te reo Māori is not just a relic of the past but a living, evolving part of New Zealand’s identity.

Meanwhile, social media has become a fertile ground for language use. Influencers, content creators, and everyday people are incorporating te reo Māori into their posts. No longer confined to classrooms and television screens, the language is making its way into the social media landscape, where it’s engaging a wide and diverse audience. This organic spread of te reo through platforms like Instagram and Twitter is transforming the way New Zealanders – and the world – interact with Māori culture.

Even within New Zealand’s corporate world, te reo Māori is finding its place. Companies like Whittaker’s Chocolate, known for its iconic products, have adopted bilingual packaging, reflecting a broader cultural shift. This embrace of te reo is not just a marketing tool but a recognition of the language’s importance to the nation’s identity, signaling a deeper commitment to acknowledging the country’s Māori roots.

While this cultural revival is exciting, it is not without its challenges. Ensuring that the use of te reo Māori in public life is authentic – rather than a superficial gesture – is a key concern for Māori leaders. The language must be integrated into daily practices in ways that reflect Māori customs and values, not just as a token of cultural competence.

With the goal of having one million New Zealanders speaking te reo Māori by 2040, the country is setting ambitious targets. The movement toward a bilingual society, where te reo Māori and English exist side by side, is well underway. And as New Zealand continues on this journey, the fusion of technology and tradition offers a model for other cultures looking to preserve their linguistic heritage in the digital age.