Localization

As a people serving and connecting to a global audience, we have come to accept that contextual adaptation is essential. Designers have addressed this need by borrowing tools from linguists, ethnographers, and cultural anthropologists, offering impactful storytelling. But words carry imagery and color and hence meaning and personality.

There was a time when customers were mere consumers and could be marketed to. Today, customers are seeking a great story beyond just a good product. Fascinating facts, ingredients, and processes capture their imagination. To them, food has become a dogmatic expression for social action. And they are questioning authenticity more – it is more like hyper-local authenticity now. Digitalization has transformed audience expectations raising levels of visual literacy at an unprecedented pace.

In diving deeper into this, we can ask, how can culture guide us in treading the DESIGN of taste?

How can food be the vector of social changes, and how can it be the way to communicate and to embrace new languages and new cultures? Food serves as a bridge and a starting point for developing new languages.

1. Recipes can be a new way to convey identities and cultures: grandmother to grandchild was a common route for transmission of information that is considered unmodern by today’s parent generation but should be reconsidered. We gain our earliest vocabulary through our matriarchal lineage, which unsurprisingly revolves around food, our primal need.

2. With the advent of technology, there was a tendency to oversimplify food recipe design. A predominance of English language cookbooks has prevailed. But today, there is a rediscovery of cultural identity’s importance which can be conveyed only with authenticity.

3. The importance of food as a way to preserve identities is shown by the fact that for migrants, food is the new language.

4. And why we need food designed for cultures.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowRecipes, the new language of food

Cookery is a multi-sensorial language without the need for words, and yet, the two oralities of tasting and talking connect us as people in myriad ways. The transfer of this knowledge through dialogue, narration, and instructions has evolved a vast vocabulary of words and expressions. Some of these are unique to hyper-regional food systems and often a beautiful catalyst of dialects.

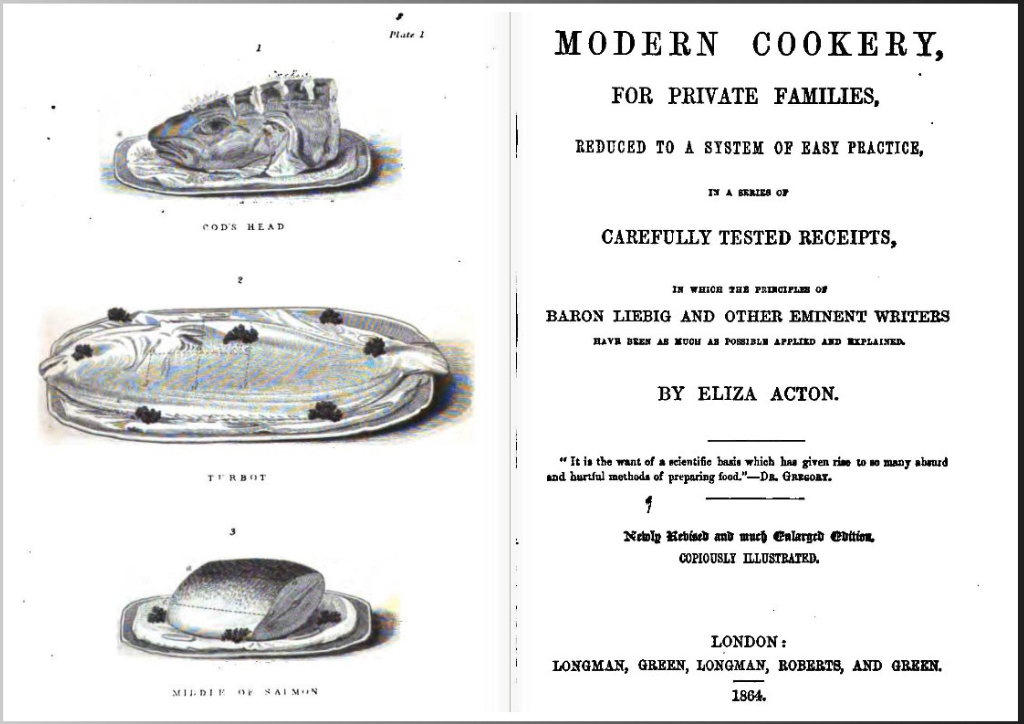

But ironically, how many cookbooks are written in their native languages? Today’s vast majority of cookbooks are written by experts in regional cuisine for an audience beyond their own, in a more broadly accepted language. Recipe writing is now dictated by templates, and publishers do not consider alternate narratives for fear of alienating their audience. Historically, recipe writing varied vastly between manuscripts and other forms of historical texts. They are often terse litotes, cook to cook, and seldom a guide for the uninitiated. It was not until Eliza Acton, in 1845, wrote ‘Modern Cooking in all its Branches’, that recipes addressed the home cook, and ingredients appeared as a list, separated by commas, noting quantities. In 1861, Isabella Beaton’s ‘Book of Household Management’ creatively rearranged Eliza’s approach to establish a template with title, body, time taken to cook, average cost, season, yield, etc. There has been no looking back since, and recipe writing has become codified. The latter half of the Acton’s book’s title: ‘Reduced to a System of easy Practice, for the use of private families, in a series of receipts, strictly tested and given in the most minute exactness’ says much of this new approach. Its land- mark success has set how cooking food must be expressed for a global audience.

The latter half of the Acton’s book’s title: ‘Reduced to a System of easy Practice, for the use of private families, in a series of receipts, strictly tested and given in the most minute exactness’ says much of this new approach. Its landmark success has set how cooking food must be expressed for a global audience.

So when hyper-regional recipes are written for a broad audience, details are swiped for the sake of brevity and ease.

This trend is not new, and there are many examples of such oversimplification. Madhur Jaffrey, writing on Indian cook- ing in the 70s, repeatedly suggests replacing coriander with parsley which would be nothing short of sacrilege in the home market! Parsley is relatively unknown in India and never used instead of coriander. But Jaffrey, in her own way, was only ensuring more people in her American audience of the time gave the recipes a try. Coriander could shy people away due to its divisive taste and sometimes unavailability. Likewise, cookbooks on Indian food often call for garam masala as if it were a simple blend, unifying diverse local expressions of taste. Over the decades, the FMCG industry responded by creating standardized spice blends that have become store cupboard staples. In the ubiquitousness of the garam masala, they have made a judgment of taste that is marginal, limited, and an inaccurate understanding of the nation’s tastes. It fundamentally disregards its profound historical, geographical, and ethnic diversity.

Commodification & a marketplace for tradition

Indian food blogs and social media channels have boomed in the last decade, with a sharp rise in platforms support- ing food journalism, longform reporting, food essays, and personal memoirs. The early wave of food bloggers wrote of food from their families and communities. Creators, mostly educated women who were homemakers, wrote recipes with personal memoirs and odes to their maternal kitchens. Incidentally, many of them were expats who had migrated from home (in India) after marriage. Drenched in nostalgia, the writing evokes loss. Their visual narratives are artifact-driven and draw deeply upon a maternal knowledge heritage. The unavailability of ingredients or intermediary food products abroad, otherwise easily found in India, meant that these creators made food “from scratch” or often found creative replacements, sharing them generously online. They described archaic practices and collated oral traditions. But they also pasted in tons of unsubstantiated text on food history and nutrition floating freely on the internet, fuelling an imagined nostalgia. They spurred a food revival unprecedented among previous generations of Indian migrants.

Reading these blogs, one gathers a sense of caste and community. In this matrix, we discover their kitchen rituals, hacks, techniques, deep insight into their values, approach to running a family, purchase decisions, and expression of a certain maternality through food. And above all, about their choice of being an educated woman of color in the kitchen today. English has been the main language in this medium, with writers adopting standard cookbook-style expressions, classification, and descriptions of techniques to ap- pear “professional” and “authoritative”. Yet, in some posts, writers insert vernacular words to express hard to describe culinary ideas or enhance authenticity – but they reflect the constraints of transferring culinary knowledge that has long depended on apprenticeship and observation.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowThe race for readership has revolutionized this homespun storytelling. In the last decade, bloggers have moved from simple recipe presentations to more detailed food writing focusing on ingredients educating their readers about health benefits, new food trends, and techniques. Some bloggers went on to introduce step-by-step visuals and well-edited short videos. Many describe investing in expensive cameras and honing their compositional skills on their blogs. As creators vied in their product, viewers reveled in this visual cornucopia. They listened to their audience, and the increasingly sophisticated online tools gave them da- ta-driven insights on their communication and the community they served.

Slowly, a critical trend began to surface – Visually attractive blogs garnered better readership, and props, colors, and stories gave individualism and style. Old plates, cooking vessels, ladles, textiles, and flowers appeared in this new vocabulary, bringing a resurgence in the interest in old utensils, of traditional grains, ancient cooking techniques, and lost recipes. In the last 10 years, this has created a whole new global marketplace for supplying traditional cooking equipment in bronze, terracotta, and stone.

With this, traditional artifacts that were earlier markers of caste and often class have become more widely available and commoditized to a large extent, blurring their divisive lines. Photography with this flavor is beginning to look more alike and bear the burden of tradition. Artifacts of utility have again assumed a new meaning, blurring the lines be- tween design and authenticity, meanings and metaphors.

FROM TOP TO BOTTOM

Thaligai vadagam (Tamil Nadu), Rajma masala (Himachal), Bisibele podi (Karnataka), Dhansak masala (Parsi community), Nihari Masala (Telangana), Goda Masala (Maharashtra), Sambhar podi (Tamil Nadu), Potli masala (Uttar Pradesh), Chole masala (Punjab) Ver masala (Kashmir).

The move from regional food to rural food

Easier access to the internet in rural India has made sharing and consuming media more accessible. It only helped that smartphones with high-quality cameras became more available at this time.

Cooking al fresco in Indian villages has emerged as viral videos on Youtube. One of the earliest to start this trend was Youtuber Arumugam Gopinath, who began filming his father cooking food in their native village in rural Tamil Nadu. Unsurprisingly, the videos are mainly in Tamil. High-quality photography skills come from the local film industry, where talent abounds. Arumugam himself was an amateur film- maker who started making these films in 2016, on returning to his village after a tough stint in the region’s film industry. Since then, dozens of such channels have started on YouTube outperforming scale, drama, and histrionics. They narrate in regional languages amplifying the sense of “local” and belonging. A few offer subtitles. Village Cooking Chan- nel is one such effort by a family of five brothers who show the complete cooking process in great detail – harvesting, foraging, or hunting, and then setting the scene for their father who prepares the dish. The focus naturally shifts to the food in the backdrop of a relatively simple stage set- ting, scant, often only essential tools. Cooking is detailed; a sense of terroir and climate sets the scenography, and the impact of a flush sense of abundance makes for great visual interest. The editing is sharp and yet offers the lingering comfort of home movies. Lesser-known ingredients, most seldom available in urban areas, create curiosity. Ironically, many of these ingredients or cooking techniques could be unhealthy if eaten daily. Some of these creators invest about €3500 a month on ingredients to make this show. With over 14m subscribers for Village Cooking Channel, the effort pays off (Sijith Payyannur “This grandad and cousins have rocked Youtube with their Village Cooking Channel”, OnManorama 2021). Strikingly, over 60% of their viewers are non-native, from the UK, USA, and Canada!

Earlier you could translate languages as a primary means of transposing cultures. Today languages alone are not sufficient, and in the context of food, perhaps less relevant. You also need visual translation and, in the future – other sensorial translations. Luckily the vocabulary of non-textual messaging is limited. For example, how many smells can humans perceive? And how universal are they, and which cultures are attuned to which smells?

An ancient food, mentioned in early Indian texts as the San- skrit parpataka. In India, they accompany the main meal and are not bar snacks or starters like in restaurants abroad. Papads are made of black lentils, rice or millets, fermented and sun-dried; they are shelf-stable products that will keep for years when made and stored well. Hundreds of different products are made on this principle, but none is meant to be a snack. They were traditionally homemade. It was not until 1959 that women in a small village in Gujarat organized themselves into a cooperative to start the production of poppadoms for sale. There is an etiquette to eating it, too – the black lentil-based papads spiced with pepper and cum- in are served with Gujarati fare. Rice-based papads (Kichiya) from Rajasthan are spiced with chilies, typically roasted on hot embers and eaten with grain-based khichdi or stews. When restaurants serving Indian foods in the West had to fit into the dining patterns of their audience, poppadoms appeared on menus as starters, just as rasam, a traditional stew, as soup. Street food became cuisine, and traditional small plates became entrees.

Historically, in India’s cuisines, the representation of foods in restaurants has been marginal, limited, and often inaccurately portrayed, perhaps elitist. The everyday foods of people’s choice of grains and protein have all been unfairly omitted.

Modernist gourmet restaurants have sprouted across India from Leh to Chennai as ideological clones to Danish dogma restaurant Noma. Most of the new restaurants are head- ed or started by those who have cut their teeth at Noma, and similar Nordic restaurants have returned home to serve an intellectually hungry, native upper class. With a care- fully simulated visual aesthetic of food reappropriation of the alma mater’s techniques and approach, these new era restaurants are articulating regional food. Heirloom ingredi- ents with pedigree and storied origins transform the Noma approach into ‘regional Indian’ cuisine. It eclipses their po- tential for a truly modern expression that connects to their culture and identity and not their time as a stagier there.

The order of service, plating, presentation, and narratives used by these modern fine dining restaurants has gathered around it an etiquette as a means of differentiating from those that still rely on regional fare. The echo of a profound epiphany – So, what must India Modern look like?

IN THE BACKGROUND

Left to right: Khichdi served with roasted khichiya papad in Rajasthan, Mung dal papad from Kathiawad & a rolling pin essentialto making papad. Resting on this are fire roasted black lentil papad from Gujarat, jackfruit papad from Kerala & tapioca pearl papad, a staple for fasting periods.

IN THE FOREGROUND

Left to Right: Pazhamum, puttu, pappadam (Kerala); Lentil papad served with ripe bananas and puttu (Kerala) Puliyogare with vadam; Tamarind flavoured rice with rice and sesame papad (Tirunelveli) Paporer dalna; Papad soaked in a sour gravy, used akin to vegetables (Bengal) Papad ke goyaane ki roti; Rotis stuffed with fresh papad dough (Gujarat) Papad churri; Crushed papad served with a dust of mango seeds, pomegranate seeds and chiilies (Rajasthan) Papad aur sharbat; Sherbet served with fire roasted papad (Sindh)

Food, designed for cultures

In a uniquely symbiotic relationship, what we eat has evolved with who we are – our occupation, geography, circumstance, and lifestyle. Food, in a sense, is a product of the culture of its people. Culture and food have co-evolved over millennia, but today, we see food being designed for cultures. For example, the cafe culture, take away culture, on-the-go culture, the ‘free-from’ culture, etc.

This last one has been the epicenter of food tech investments in India. The land of the holy cow has woken up to vegan possibilities with a crop of well-funded startups offering milk and meat alternatives. These companies have struggled to find the right product-market fit as Indians are a “taste-first” audience with an ancient heritage of animal-free foods. Ironically, India is not a predominantly vegetarian or vegan society, contrary to popular belief. The country’s varied geographies and long coastlines mean people have a thriving omnivorous appetite.

India’s youth do not want to be marketed just a plant-based alternative but also the right visual and ethical storytelling that speaks their life at the cusp of traditionalism, globalization, and genetic predisposition to metabolic conditions. India’s “free-from” startups have used locally grown cashew and oats (predominantly European import), soy, wheat, and peas for the plant-based milk alternatives. But to be accessible and affordable, two of the most prominent players in this field are launching millets (in 2022) as the new raw materials for milk alternatives. Millets have been a local crop for millennia and are better placed than. They have experienced a huge resurgence with the earlier-discussed blogger-driven revivalist trend. Millet-based free-from food alternatives have had an existence in the blog universe for a few years now but have not gone mainstream until now.

Also, plant-based meat alternatives are an area of intense competition in India. Interestingly in India, this is not just for the ethically-minded, and the climate-conscious, who will move away from meat, but also for the ethnically vegetarian whose main criteria for abstaining from meat has been religious dictums. The younger generation ethnically-vegetarians are curious and open to tastes and textures, as long as their religious frameworks can be upheld.

Food tech startups leading India’s free-from revolution are now exploring locally grown hardy millets and pseudo cereals in a unique and fascinating approach.

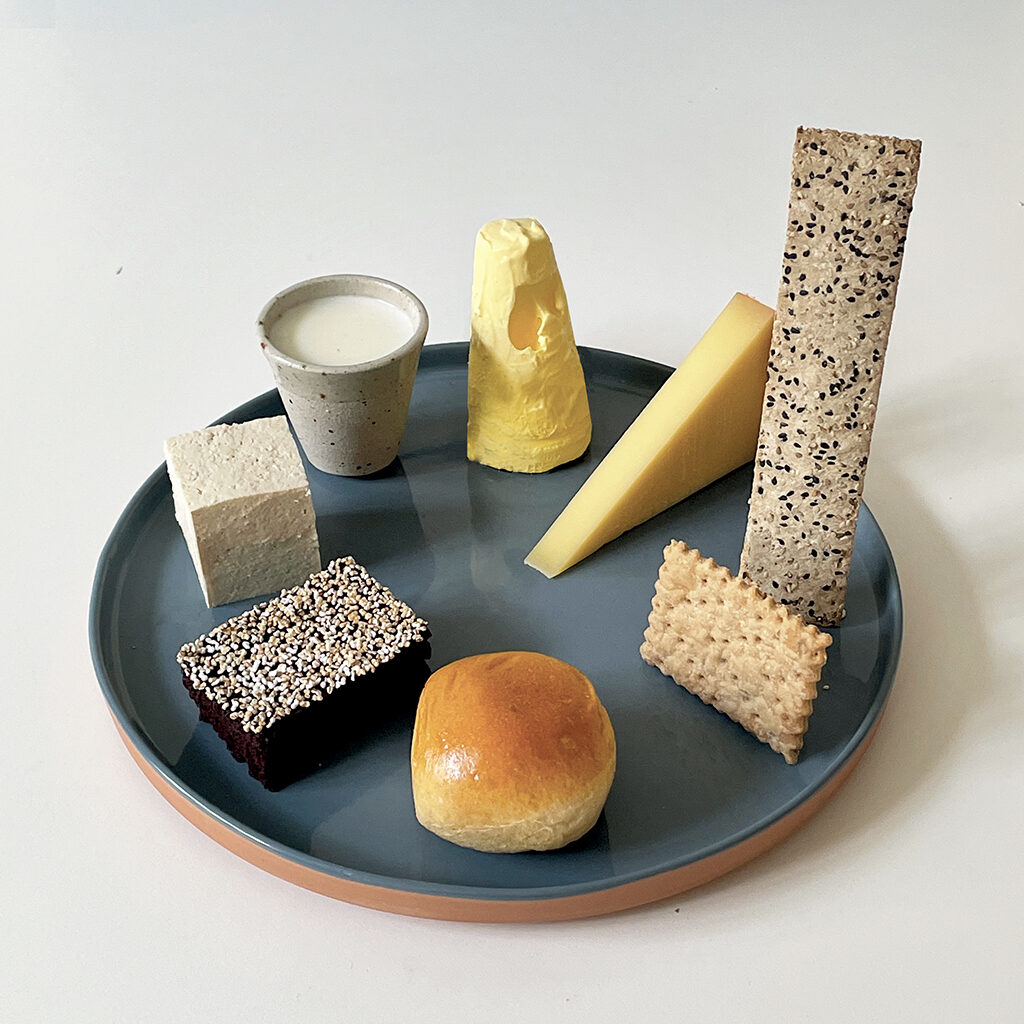

Clockwise: Traditional Indian ice cream, kulfi, made from locally grown cashew milk; proso millet based cheese, crackers and biscuits from buckwheat and barnyard millet, plant-based brioche, finger-millet brownie with popped amaranth, fox tail millet Indian paneer, little millet based milk.

Photo credits: Priya Mani