Language

The Brazilian Portuguese:

From the Near Disappearance to the Hegemonic Pretoguês

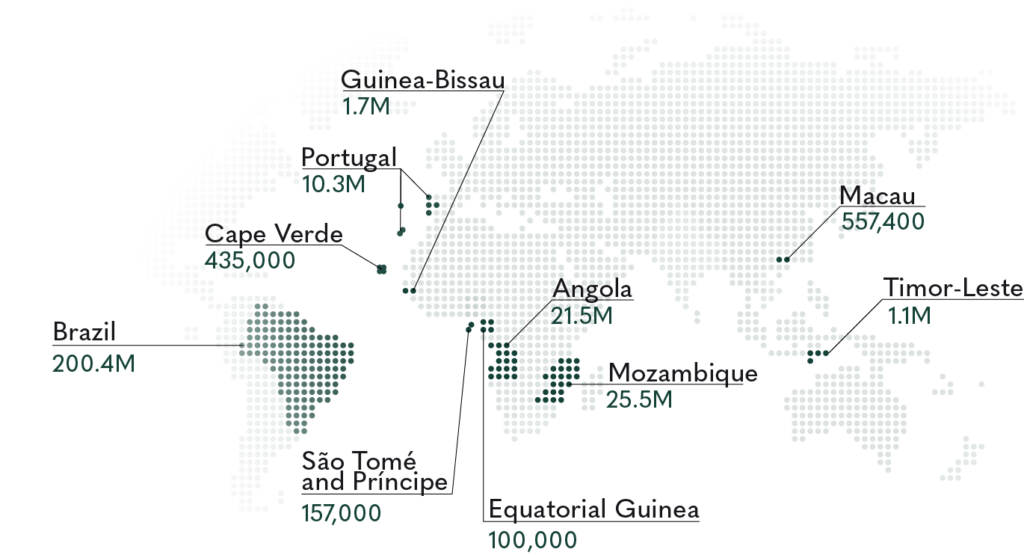

We speak the language of the colonizer. I can’t remember who said that, but it holds true for most Brazilians — at least for those born since the 18th century, in what was once a Portuguese colony in South America. Today, Brazil’s population speaks Portuguese, a language shared by around 260 million people worldwide (Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Macau, Mozambique, Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe, East Timor, Goa, Daman and Diu).1 It ranks as the 5th most spoken language by native speakers globally,2 the 3rd most spoken on the internet,3 and the most spoken language in the Southern Hemisphere.4 Projections by the United Nations suggest that by 2050, there will be 400 million Portuguese speakers, and by 2100, 500 million.5 Only in Brazil is Portuguese the official language of around 200 million people.

But this wasn’t always the case. Some linguists argue that the Portuguese spoken in Brazil isn’t truly Portuguese — or at least not in its supposedly original form. The version of Portuguese brought by the first Portuguese explorers (sailors and then settlers) to the new colony, influenced by the contact with Native Brazilian people and the millions of enslaved Africans brought to Brazil over during the roughly 350-year transatlantic slave trade (which lasted from the 16th to the 19th century, approximately 1500 1850, even though slavery would only be officially abolished in Brazil in 1888), gradually evolved into a unique variety of Portuguese from the 18th century onwards, the so-called Brazilian Portuguese.

How could a language born in the northern part of the territory known today as Galicia, evolving from the medieval Galician-Portuguese spoken in the Kingdom of Galicia, be brought by Portuguese explorers to the New World in the 16th century, spread across a landmass spanning over 5,000 kilometers from north to south — what we now call Brazil — and, against all odds, become the effective and official language of over 200 million people?

As some linguists argue, the Brazilian version of Portuguese is more than a variety — it is its version of a language: a language that is embedded and rooted in the horrific and disturbing African Diaspora that came into Brazil due to slavery, something that would reshape the country’s history and, undoubtedly, the language. As noted by professor and sociolinguist Yeda Pessoa de Castro,6 a leading expert on African influences on Brazilian Portuguese, Brazilian Portuguese — or simply Brazilian, as some linguists and activists refer to it — is a direct product of these cultural encounters.

For over 350 years, it is estimated that approximately 5 million enslaved Africans (men, women and children)7 — first brought to work on sugar plantations in the 16th and 17th centuries, and later, more significantly, during the 18th-century gold rush, particularly in the city of Ouro Preto (meaning Black Gold), then known as Vila Rica (Rich Village) in the state of Minas Gerais (General Mines) — were brought to Brazil, forced to work and sold as mere products.

States and territories with Portuguese as the Official Language

Source: Porto University

When discussing African and Indigenous influence on Brazilian Portuguese, many often cite, somewhat superficially, terms related to topography and cuisine as evidence, as the Portuguese brought from Portugal was subtly flavored by these words and expressions. However, the Brazilian language was profoundly reshaped by the brutal historical processes of colonization, so much so that, through a series of coincidences, it altered the very structure of Portuguese, forging its grammar, syntax, prosody, and rhythm. So much so that the Black activist Lélia Gonzales even coined a term to refer to the Brazilian Portuguese — Pretuguês or Pretoguês (the junction of the words Português and Preto, meaning black).8

Most of the Africans who came to Brazil spoke Bantu languages (such as Kikongo, Kimbundu, and Umbundu), as well as languages from the Gbe groups (like Fon and Ewe) and Niger-Congo languages (such as Yoruba), languages which, coincidentally, share a similar syllabic structure of vowels and consonants with Portuguese. This is key to understanding the formation of what is called Brazilian Portuguese. Not only that, but recent studies also argue that the African presence in Brazil, paradoxically, facilitated the hegemonic spread of the language across its vast territory.9

And if that is the case, it’s nothing short of a miracle. How could a language born in the northern part of the territory known today as Galicia, evolving from the medieval Galician-Portuguese spoken in the Kingdom of Galicia, be brought by Portuguese explorers to the New World in the 16th century, spread across a landmass spanning over 5,000 kilometers from north to south — what we now call Brazil — and, against all odds, become the effective and official language of over 200 million people?

Covering a total area of 8.5 million square kilometers, Brazil is the largest country in South America and, despite its many regional varieties (and there are many), Brazilian Portuguese remains relatively stable and hegemonic. This means you can travel across Brazil in any direction and still be understood, even with the specific grammatical constructions and vocabulary unique to each region. Yes, in South America, the most widely spoken language isn’t Spanish — it’s Portuguese, Brazilian Portuguese; the Pretoguês.

Language

Imminent Section

Step into Imminent’s language section, where leading voices share sharp insights on the evolution of languages and localization.

Read MoreThe Celts, Rome and the Moors

To understand the formation of Brazilian Portuguese and the unique characteristics that make it distinct, inevitably, we must board the caravelas (caravels) for a return journey to the European continent.

The Portuguese language, like French, Spanish, Italian, Catalan, Galician, Romanian, and others, belongs to the group of languages known as the Romance languages. These languages are part of a larger linguistic family that traces its roots to Proto-Indo-European, a hypothetical tongue spoken by a group of people who lived in the region that is now Ukraine about 6,500 years ago and spread over Europe, also being the origin of languages like Greek, Sanskrit, and Latin.

Today, whenever Brazilians and other Portuguese speakers say the word barro (clay), they connect to a lineage of speakers who have kept this term in use for at least 5,000 years.

The Celts and Italic Celts, branches of the Indo-European migration, arrived on the Iberian Peninsula around the first millennium BCE. They shared linguistic and cultural affinities with peoples such as the Gauls and the inhabitants of the British Isles, who later gave rise to French, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh. In Iberia, they encountered the Iberians, an older civilization, whose presence in the region dates back 40,000 years. The Basque language, possibly one of the few non-Indo-European languages on the continent, is seen as a legacy of these pre-Indo-European peoples.

The interaction between the Celts and Iberians gave rise to Celtic-Iberian culture, which left its marks on the language spoken in the region. Just a quick example of a Celt-Iberian word is the word “barro”. Today, whenever Brazilians and other Portuguese speakers say the word barro (clay), they connect to a lineage of speakers who have kept this term in use for at least 5,000 years. Or maybe even longer. However, tracing a linear history of Celtic influence is complex, as many Celtic-origin words may have been introduced by the Romans, who already had contact with other Celtic peoples.

With the expansion of the Roman Empire, Latin reached the Iberian Peninsula and became the dominant language. However, Latin, as the invading language, absorbed elements from local languages. It’s important to clarify that the Latin imposed on the population and learned through oral expression was not the classical Latin of Virgil and other poets or the language of senate, but the plebeian way of speaking — a simplified, “broken” Latin used as a lingua franca out of necessity. The process of language development is always a process of “damaging” the original. Portuguese, like other Romance languages, emerged from the informal speech of people without formal education, who learned by ear and inevitably imprinted their unique traits onto the language, the analphabets (without alphabet). The most formal Portuguese spoken and written today is, in essence, a broken version of Latin — or, as professor and translator Caetano Galindo aptly describes it in his book “Latin in Dust” (Latim em Pó), “Our most refined Portuguese is little more than a clumsy Latin.” This book served as the basis for most of what I am saying here.

The Arabic influence, while it did not leave a clear mark on Portuguese grammar, remains deeply significant in the culture.

Soon enough, the Portuguese would receive a heavy influx of influence from the people of Northern Africa, the Berbers, who became known as the Moors. The word “Moor” originates from the Latin word “Maurus,” which the Romans used to refer to the Berber inhabitants of North Africa. Over time, the term “Moor” came to encompass the entire Islamic culture in the Iberian region, which included people of both Arab and Berber descent. The term, originally used to refer to the Berbers from North Africa, came to represent Islamic culture in the region and, over time, was also associated with skin color, giving rise to Portuguese words like moreno or morena (dark-skinned).10 The Arabic influence, while it did not leave a clear mark on Portuguese grammar, remains deeply significant in the culture.

Portuguese words like açúcar (sugar), café (coffee), algodão (cotton), azeite (oil), garrafa (bottle), and almofada (cushion) trace their roots back to Arabic. Additionally, some words, such as azul (blue), have Persian origins, highlighting the interconnectedness of various cultural influences, as well as everyday expressions like Oxalá (from Arabic wa xa’llah, God willing). Beyond language, architecture, music (such as flamenco and fado), and even daily customs were shaped by this coexistence. The influence of the Muslim presence in Portugal is still evident in the population’s genotype and phenotype.

So, this is the caldo (how do you say that in English? Perhaps “broth” or “mix”?) that would disembark in what is today the southern part of Bahia, Porto Seguro, on April 22, 1500, when the Portuguese arrived in the land that would become known as Brazil: a fragmented, Celtiberian-influenced Latin, shaped by over 700 years of Arab influence and its layers of cultural blending. The Portuguese in Brazil — or Ilha de Vera Cruz, the first name given to Brazil by the Portuguese. Due to their strong Catholic devotion, they often named newly “discovered” places in honor of Christ. Many of their caravelas were believed to carry pieces of wood from the real Cross of Christ, which added a sacred significance to their voyages.

And so, after a few lines and heavy winds, we are back to Brazil, not to leave anymore. And here they are, together with the Portuguese and the Portuguese language, the people who for thousands of years have inhabited these lands, the native indigenous people.

Línguas Gerais: The Near-Death of Portuguese in Brazil

When the Portuguese first arrived in Brazil on April 22, 1500, it was estimated that over 1,000 indigenous languages were spoken across the country. By 2010, official demographic research in Brazil revealed that only a little bit over 200 of these languages remain, a third of them with less than one hundred speakers.11 While the Portuguese initially arrived in 1500, substantial colonization, marked by the establishment of the first sugar plantations, began around 1550. The initial plan was to utilize indigenous people as labor, and this centuries-long interaction led to the development of Línguas Gerais (general languages), serving as língua franca across the colony.

The Línguas Gerais (General Languages) in Brazil do not fit the traditional definition of creole languages, especially the Portuguese-based creoles that developed in other Portuguese colonies, such as Guiné Bissau, São Tomé, Goa or Diu (India). Instead of a fusion of Portuguese vocabulary with the grammar of native languages, they represented an adaptation of Tupi branched languages, especially Tupi antigo (Old Tupi), widely spoken in the coast of Brazil at the time of the Portuguese arrival. The Portuguese colonizers, in a strategy of domination, appropriated these languages to facilitate the catechization, control, and colonization of indigenous peoples.

Two main varieties of general languages developed in Brazil. The southern general language, also known as Paulista or coastal general language, derived from the Tupiniquim spoken in São Vicente and the coast of Sao Paolo. It circulated widely on the coast and in the Brazilian backlands, areas influenced by Paulista culture, until the end of the 18th century. Concurrently, Nheengatu (good language), developed from a variety of Tupinambá in the North of the country, remaining in use until the 19th century and being recognized, in 2002, as an official language of the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, in the state of Amazonas.

The general languages were not restricted to marginalized or enslaved groups. They became the main language of communication for the local population, both in the countryside and in the nascent Brazilian cities. Several records from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries attest to the predominance of general languages among Brazilians. Documents written by Portuguese from the kingdom frequently lamented the difficulty of finding Portuguese speakers in the colony.

But how did Brazil, a vast continent-sized country, transition from Línguas Gerais to having Portuguese as the hegemonic language spoken by over 200 million people?

The situation changed drastically with the implementation of the Indian Directory, a policy of the Marquês de Pombal that institutes the teaching of the Vernacular language in the country. The expulsion of the Jesuits, who used general languages to catechize, also accelerated the decline of these languages. The Directory was the culmination of a process of modernizing the colony, which generated greater interest and interference from the Portuguese metropolis. Local elites supported the strengthening of Portuguese rule, and general languages lost relevance in a changing social structure, marked by the centralization of power and cultural homogenization. In the North of Brazil, Nheengatu had a path with similarities and singularities about the decline of general languages. Nonetheless, the demographics of the region, with a greater indigenous presence and a more direct interaction with Europeans, allowed Nheengatu to resist for longer.

But how did Brazil, a vast continent-sized country, transition from Línguas Gerais to having Portuguese as the hegemonic language spoken by over 200 million people? One of the factors, or maybe the most important one apart from the ones mentioned already, is the African people who arrived forcefully as slaves in Brazil for nearly four centuries.

Pretoguês: A Mother Language

The separation of ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and family groups was a common practice among enslaved people traffickers in Brazil. The initial goal of this strategy was to reduce the influence of African cultures and languages in Brazilian society by fragmenting communities and making it more difficult for them to preserve their traditions. The Africans brought to Brazil as enslaved people were predominantly speakers of Bantu languages (such as Kikongo, Kimbundu, and Umbundu), as well as languages from the Gbe group (like Fon and Ewe) and the Niger-Congo group (such as Yoruba). Most of them originated from the western part of the continent, particularly from a region that began in the ancient Kingdom of Benin and extended across the entire Gulf of Guinea, including the present-day coast of Angola. Other groups were also represented, but those mentioned above were the most numerous to arrive in Brazilian territory. Some Africans also arrived speaking and writing Arabic, due to the Islamization of their homelands, as in the case of the Malês.

The continuous interaction among diverse African groups and the necessity for communication fostered the incorporation of African linguistic elements into Portuguese.

Many enslaved people arrived in Brazil with some knowledge of the Portuguese language. This phenomenon was partly due to the growing presence of Portuguese in Angola, where the language was used in coastal trading posts as a means of communication between speakers of different languages. The long waiting periods before embarkation and the transatlantic voyages themselves also contributed to this diffusion. During the crossing, interpreters known as línguas (languages) facilitated communication between the enslaved people and the crew, easing their initial contact with the language.12

Thus, despite efforts to fragment African groups, the strategy of disarticulation may have inadvertently become one of the key factors contributing to the widespread use of Brazilian Portuguese, now spoken by over 200 million people in a continent-sized country. This process played a significant role in the homogenization of Portuguese as it is spoken in Brazil today. The continuous interaction among diverse African groups and the necessity for communication fostered the incorporation of African linguistic elements into Portuguese — though, as we will see, not exclusively linguistic elements.

The transmission of Portuguese in Brazil was largely facilitated by women, particularly African and Indigenous mothers, who raised generations of mixed-race children. Many of these women spoke African languages or the Línguas Gerais, which had evolved into a lingua franca. Consequently, children were born and raised in an environment where Portuguese intermingled with other languages, creating a unique linguistic blend.

Furthermore, the strong maternal influence in language formation — often in the context of colonial violence, where European men fathered children with Indigenous and Black women — shifted the responsibility for passing on the language to these women. This process also explains the emotional resonance of many native terms incorporated into Brazilian Portuguese: the words caçula (used to refer to the youngest child in the family) and cafuné (used to describe the act of lovingly stroking someone’s head), of Bantu origin, carry a deep sense of affection in Brazilian Portuguese and are strongly associated with childhood.

Brazil

Language Data Factbook

The Language Data Factbook project aims to make the localisation of your business and your cultural project easier. It provides a full overview of every country in the world, collecting linguistic, demographic, economic, cultural and social data. With an in-depth look at the linguistic heritage, it helps you to know in which languages to speak to achieve your goal.

Discover it here!For Professor Yeda Pessoa de Castro, the so-called “interference” of these languages is not merely a superficial contact but rather a deep process of transformation.13 Instead of simply learning Portuguese, African populations from multilingual backgrounds significantly altered it, subjecting it to a kind of “distillation” that reshaped its structures. This perspective challenges the traditional view that African languages had only a minor influence on Portuguese. Instead, Yeda argues that Bantu languages acted as a superstratum, absorbing and reshaping the dominant language in the territories where Africans were integrated. In this sense, the role of African speakers in the development of Brazilian Portuguese was not marginal, but structural and essential.14

By a strange and horrific coincidence, almost 75% of the enslaved population that set foot on Brazilian land spoke languages of Bantu origin languages.15 The coincidence relies upon the fact that the Bantu languages, spoken by many Africans who came to Brazil, share characteristics with the Portuguese language. One such feature is their syllable structure, which tends to allow syllables composed of a consonant followed by a vowel (CV), with no consonant clusters or syllables ending in a consonant.

This may explain phenomena in Brazilian pronunciation, such as the more complete preservation of Latin vowel sounds (it is believed that the pronunciation in Brazil today is quite similar to what spoken in Portugal at the Age of Discovery).

Examples of unique linguistic phenomena in Brazilian Portuguese

The insertion of vowels to break up consonant clusters

- Rítimo instead of ritmo (rhythm)

- Téquinico instead of técnico (technical)

The dropping of the final r in infinitives

- Catá instead of catar (to catch),

- Fazê instead of fazer (to do/make)

- Medí instead of medir (to measure)

The difficulty in pronouncing words with two consecutive consonant clusters

- Própio instead of próprio (proper/own)

- Poblema instead or problema (problem)

- Dible instead of drible (dribbling)

Additionally, Bantu languages form the plural by changing prefixes, as in muntu (person) and bantu (people). This feature may have reinforced the tendency in Brazilian Portuguese to mark pluralization primarily on the article rather than the noun, as seen in examples like as coisa (the thing) instead of as coisas (the things). Interestingly, the English language has a similar pattern.

From Colonizer to Ours: The Brazilian Language

It goes without saying that the informal and widely spoken variety of Brazilian Portuguese, particularly used by Black and mixed-race communities in certain contexts, has long been stigmatized. The prevailing belief that only standard Portuguese — rooted in European norms — is legitimate has fostered a linguistic inferiority complex in Brazil. Many Brazilians have come to believe that they do not speak their own language correctly, despite the richness and complexity of their linguistic practices. For instance, the simplification of nominal and verbal agreement, a common feature of popular Brazilian Portuguese, is often misinterpreted as a sign of linguistic deficiency rather than a natural evolution of the language. Moreover, the difficulty of translating Black English into Brazilian Portuguese underscores the lack of recognition for Black linguistic forms within the Brazilian context. This not only creates a cultural gap but also risks reducing these forms to caricatures when attempts are made to represent them. This issue is further compounded by the disconnect between the Brazilian Portuguese spoken and written by its people and the grammar books, most of which adhere strictly to European Portuguese norms. This disparity has caused confusion and challenges in language education across the country.

Yes, we do speak the language of the colonizer, but not in the same way anymore. It is now ours: a living, evolving language that reflects the experiences and identities of its speakers.

The spread of Portuguese in Brazil — shaped by Portuguese colonization and its consequences, including the horrors of slavery and the forced migration of the Black population — alongside the central role of women in transmitting the language, ultimately led to the stigmatization of certain linguistic varieties. This marginalization is deeply rooted in racial prejudices and social inequalities that have systematically devalued the contributions of enslaved Africans to the development of Brazilian Portuguese. Yes, we do speak the language of the colonizer, but not in the same way anymore. It is now ours: a living, evolving language that reflects the experiences and identities of its speakers. Interestingly, in Portugal and other Portuguese-speaking countries, there is growing concern about the influence of Brazilian Portuguese, particularly through the internet. In Portugal, for example, children are increasingly adopting brasileirismos (Brazilianisms), using words like ônibus instead of autocarro (bus), grama instead of relva (grass), and geladeira instead of frigorífico (refrigerator).16 This shift is largely driven by the global reach of platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok — a process of cultural influence that began decades ago with the widespread popularity of Brazilian soap operas in Portugal, for instance — as well as the sheer volume of online content produced in Brazilian Portuguese (recall that Portuguese is the 3rd most used language on the internet).

If we imagine language as a sea, vocabulary represents the surface, the most visible and dynamic layer, where waves occur rapidly but may also be fleeting. Linguists argue that while Brazilian Portuguese has a significant influence on European Portuguese, particularly in vocabulary, deeper grammatical and phonological changes are slower to take hold. This means that while Portuguese speakers in Portugal may adopt Brazilian words, they are unlikely to fully adopt Brazilian Portuguese as their own.

Anyway, there is a certain irony in this linguistic journey: a language born from the mix of Celt-Iberian, clumsy Latin on the Iberian Peninsula, carried across the ocean by colonizers, transformed by centuries of colonization and its devastating consequences, now returns to the mouths of the Portuguese reshaped, reimagined, and alive with the voices of those who once were silenced.

Gustavo da Rosa Rodrigues

Brazilian Portuguese Linguist Expert

Gustavo da Rosa Rodrigues holds an undergraduate degree in Letters and Translation Studies. Over the past six years, he has worked as a translator, collaborating with Translated on various translation projects. He is the author of the poetry book "Um levantar de paredes" (Urutau, 2019).

References

1. Dia Mundial da Língua Portuguesa. (2022, May 5). (n.d.).

2. Statistics, in Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2025). Ethnologue.

3. Universidade do Porto. (2019, May 30). O Português no Mundo -Portal do Português da UP- up.pt/portuguesuporto.

4. Dia Mundial da Língua Portuguesa. (2022, May 5). (n.d.).

5. Dia Mundial da Língua Portuguesa. (2022, May 5). (n.d.).

6. Museu da Língua Portuguesa. (2022, May 6). Camões com Dendê, com Yeda Pessoa de Castro e Caetano Galindo.

7. Rossi, A. (2018, August 7). Navios portugueses e brasileiros fizeram mais de 9 mil viagens com africanos escravizados. BBC News Brasil.

8. Araujo, R. (2023, February 3). O pretuguês de Lélia Gonzalez. Introcrim.

9. Galindo W. C. Latim em Pó: um passeio pela formação do nosso português. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2022.

10. Los Hermanos – Morena (Video Clip).

11. Galindo W. C. Latim em Pó: um passeio pela formação do nosso português. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2022.

12. Galindo W. C. Latim em Pó: um passeio pela formação do nosso português. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2022.

13. São Paulo: Contexto, 2019. CASTRO, Yeda Pessoa de. Camões com dendê: o português do Brasil e os falares afro-brasileiros. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 2022.

14. Museu da Língua Portuguesa. (2022, May 6). Camões com Dendê, com Yeda Pessoa de Castro e Caetano Galindo.

15. Galindo W. C. Latim em Pó: um passeio pela formação do nosso português. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2022.

16. Braun, J. (2024, April 6). O português de Portugal está ficando mais brasileiro? As expressões ouvidas com cada vez mais frequência no país. BBC News Brasil.