Language

Arabic is the official language, spoken by 88% of the population. It is estimated that 20% of the population speaks French in everyday life, but 65% of residents are capable of reading and conversing in French.

English is spoken by 30% of the population, but the majority of residents are able to understand it.

In the streets of Lebanon’s cities, the main languages you’ll hear spoken are French, Arabic and English, but you might also happen to hear some Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, German or Danish. What sets Lebanon apart from any other multilingual country is that code-switching is not limited to spoken conversations – it is also reflected in the written language.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowIn the 1990s, the government sanctioned teaching in three languages: Arabic, French and English. These languages were formally described as an official mother tongue and two foreign languages, and today they are all gradually introduced as part of primary schooling.

This means that the main language used in education is not always Arabic; instead, it varies from school to school. In particular, public and private schools differ in this respect: in most private schools, the foreign languages (French and English) are used to teach certain topics considered to be of particular importance, such as science and mathematics. When it comes to local opinions on language, English and French are generally seen as more useful than Arabic for entering the world of work.

In any case, the languages used most by the local population – as always – often end up being those used most in the education system. The languages used in Beirut’s public spaces, besides Arabic, are thus mainly French and English, with a certain number of other languages in a minority.

This means that Lebanon’s population is used to reading two different types of writing: the Arabic type, written from right to left in one alphabet, and the French and English type, written from left to right in another. There are also two different numbering systems: the western ‘Arabic’ numerals that we are familiar with in the west (‘0, 1, 2, 3’) and the eastern ‘Arabic-Indic‘ numerals (‘٠ ١ ٢ ٣’).

And so it is that, in Beirut, in certain formal contexts such as on road signs, the inscriptions of public buildings or the facades of monuments, we can find the same messages in two or three languages.

One might think that the mix of languages exists to respond to the needs of districts where there are high numbers of foreign residents. On the whole, however, the linguistic panorama in Beirut is made up of multilingual literacy and multilingual writing because it reflects the multilingual population that lives there.

It might seem like a chaotic linguistic scenario: After all, it’s very rare to find the same message on a public sign written in three different languages, or rather using a mix of languages and characters. In addition, the Arabic language can be written with both Arabic letters and using the Latin alphabet.

Western languages are usually written with the Latin alphabet, but on old road signs (on the back roads of Hamra, for example), we can find them transliterated using the Arabic alphabet. Phrases written in the Arabic alphabet can be accompanied by either numbering system, but writing in English is typically seen alongside the western ‘Arabic’ numerals.

However, the important aspect to grasp here is not the chaos, but the fundamental expectation that everyone in Lebanon has a certain level of literacy in Arabic, French and English. It is not unusual to find languages, scripts and numbering systems used together in a way that does not replicate the meaning of the principal message, but instead complements it. This detail indicates the fact that literacy in Beirut is highly contextual. Linguistic diversification is therefore rooted in a complex series of cultural values to which local communities assign different priorities in different ways and in different places.

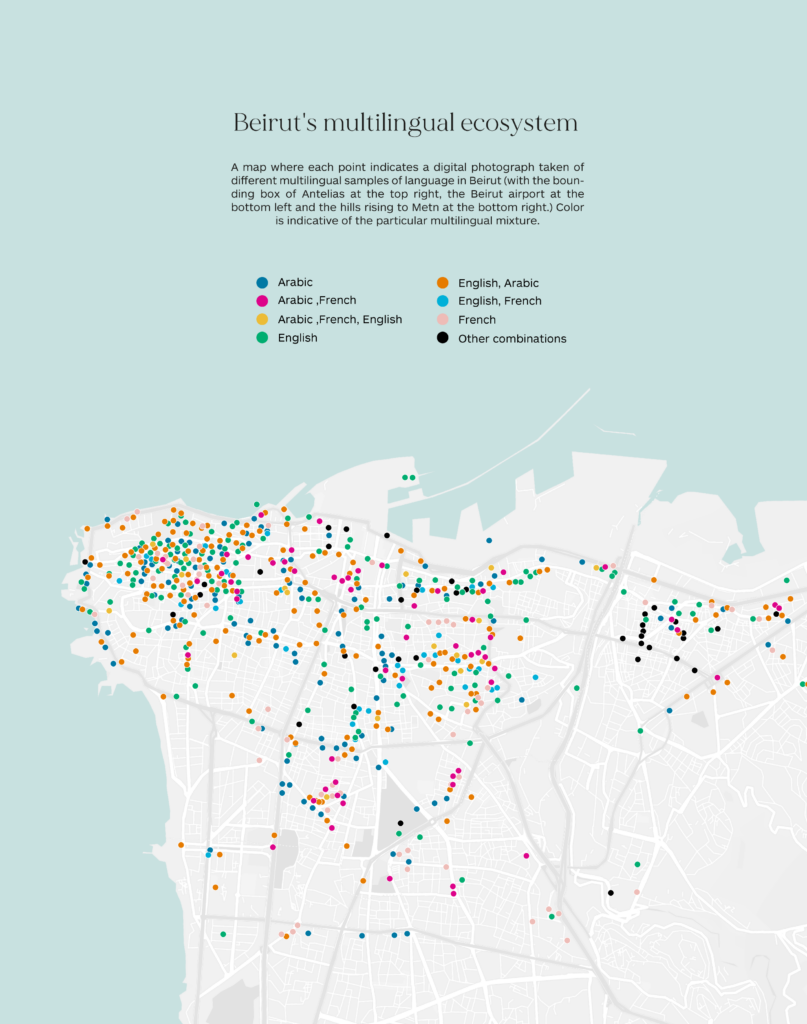

In an attempt to illustrate Beirut’s complex linguistic landscape, a team of over 40 students from the American University of Beirut travelled around the city with their smartphone cameras taking photographs of everything, from road signs and shop awnings to advertising posters and graffiti. The map below summarises the results of this research: a map on which each point indicates a digital photograph of the various multilingual samples found in Beirut’s language. The colour indicates the particular multilingual blend in question.

Research supports the fact that, throughout history, multicultural cities have had more chance of surviving than monocultural ones, demonstrating that the multilingual ecosystem photographed here represents not an obstacle but an opportunity. But there’s more: creative projects are also being developed that use multilingualism to bring to life new design concepts, taking their inspiration from linguistic complexity while at the same time giving a shape and a voice to a new form of linguistic coexistence.

The image shows a Lebanese design brand called Art 7ake (‘Word Art’) that showcases the innovative use of Arabic words depicted in images combined with English text. On the left, the Arabic word for ‘tea’ is shay, which is pronounced the same as the English word ‘shy’, hence the image of a teabag. Such a design would look and sound weird to an English speaker who does not know the Arabic word for ‘tea’. In the middle picture, the word ‘mouse’ means ‘far’ in Arabic, which explains the image of the mouse. The picture on the right uses the same design concept: ‘tore’ in English means ‘ox’ in Arabic.

French

Un hub multilingue

Le Liban, connu pour son système éducatif multilingue et la mobilité internationale de son importante diaspora, abrite un écosystème linguistique très intéressant.

L’arabe est la langue officielle, parlée par 88 % de la population. On estime que 20 % de la population parle français dans la vie quotidienne, mais que 65 % des résidents peuvent lire et converser en français.

L’anglais est parlé par 30 % de la population, mais la majorité des résidents le comprennent.

Dans les rues des villes libanaises, les principales langues que vous entendrez sont le français, l’arabe et l’anglais, mais vous pourriez aussi entendre parler espagnol, portugais brésilien, allemand ou danois. Ce qui distingue le Liban de tout autre pays multilingue, c’est que l’alternance des co- des ne se limite pas aux conversations orales : il se reflète également dans la langue écrite.

Dans les années 1990, le gouvernement a approuvé l’enseignement en trois langues : l’arabe, le français et l’anglais. Ces langues sont donc devenues la langue maternelle (arabe) et deux langues étrangères officielles (français, anglais), et elles sont aujourd’hui sont toutes les trois introduites progressivement dans l’enseignement en école primaire.

La langue principale utilisée dans l’éducation n’est pas toujours l’arabe, cela varie d’une école à l’autre. Les écoles publiques et privées diffèrent à cet égard : dans la plupart des écoles privées, les langues étrangères (le français et l’anglais) sont utilisées pour enseigner certains sujets considérés comme particulièrement importants, tels que les sciences et les mathématiques. Pour ce qui est de l’opinion publique locale sur le sujet de la langue, l’anglais et le français sont généralement considérés comme plus utiles que l’arabe pour entrer dans le monde du travail.

oXXIgen

Imminent Research Report 2022

GET INSPIRED with articles, research reports and country insights – created by our multicultural interdisciplinary community of experts with the common desire to look to the future.

Get your copy nowQuoi qu’il en soit, les langues les plus utilisées par la population locale finissent, comme toujours, par être celles qui sont le plus utilisées dans le système éducatif. Les langues utilisées dans les espaces publics de Beyrouth, outre l’arabe, sont donc principalement le français et l’anglais, avec un certain nombre d’autres langues plus minoritaires.

La population libanaise a l’habitude de lire deux types d’écriture différents : l’arabe d’une part, qui s’écrit de droite à gauche, et le français et l’anglais d’autre part, qui s’écrivent de gauche à droite, ces deux types de langues ayant chacun un alphabet différent. Il existe également deux systèmes de numérotation différents : les chiffres « arabes » occidentaux que nous connaissons (« 0, 1, 2, 3 ») et les chiffres « indo-arabes » orientaux (« ٠ ١ ٢ ٣»).

C’est ainsi qu’à Beyrouth, dans certains contextes formels comme sur les panneaux routiers, les inscriptions des bâtiments publics ou des façades des monuments, on peut trouver les mêmes messages rédigés en deux voire trois langues.

Au premier abord, on pourrait penser que ce mélange des langues a pour objectif de répondre aux besoins des quartiers où vivent de nombreux résidents étrangers. Mais dans son ensemble, le panorama linguistique de Beyrouth est constitué d’une alphabétisation et d’une écriture multilingues parce qu’il reflète tout simplement la population multilingue qui y vit.

Cela peut sembler un scénario linguistique pour le moins chaotique. En effet, il est très rare de trouver le même message sur un panneau public écrit en trois langues différentes, ou plutôt en un mélange de langues et de caractères différents. Par ailleurs, la langue arabe peut être écrite à la fois en lettres arabes et en alphabet latin.

Les langues occidentales sont généralement écrites avec l’alphabet latin, mais sur les anciens panneaux routiers (sur les routes secondaires de Hamra, par exemple), on peut les trouver translittérées à l’aide de l’alphabet arabe. Les phrases écrites en alphabet arabe peuvent être accompagnées de l’un ou de l’autre système de numérotation. L’écriture en anglais est cependant affichée en général à côté des chiffres « arabes » occidentaux.

L’aspect important à saisir ici n’est pas cette apparente complexité, mais plutôt qu’on s’attend vraiment à ce que tout le monde au Liban possède un certain niveau de com- préhension en arabe, en français et en anglais. Il est monnaie courante de trouver des langues, des écritures et des systèmes de numérotation utilisés ensemble d’une manière qui ne reproduit pas le sens du message principal, mais qui au contraire le complète. Ce détail indique le fait que l’alphabétisation à Beyrouth est hautement contextuelle. La diversification linguistique est donc ancrée dans une série complexe de valeurs culturelles auxquelles les communautés locales accordent des priorités différentes, de différentes manières et dans des lieux différents.

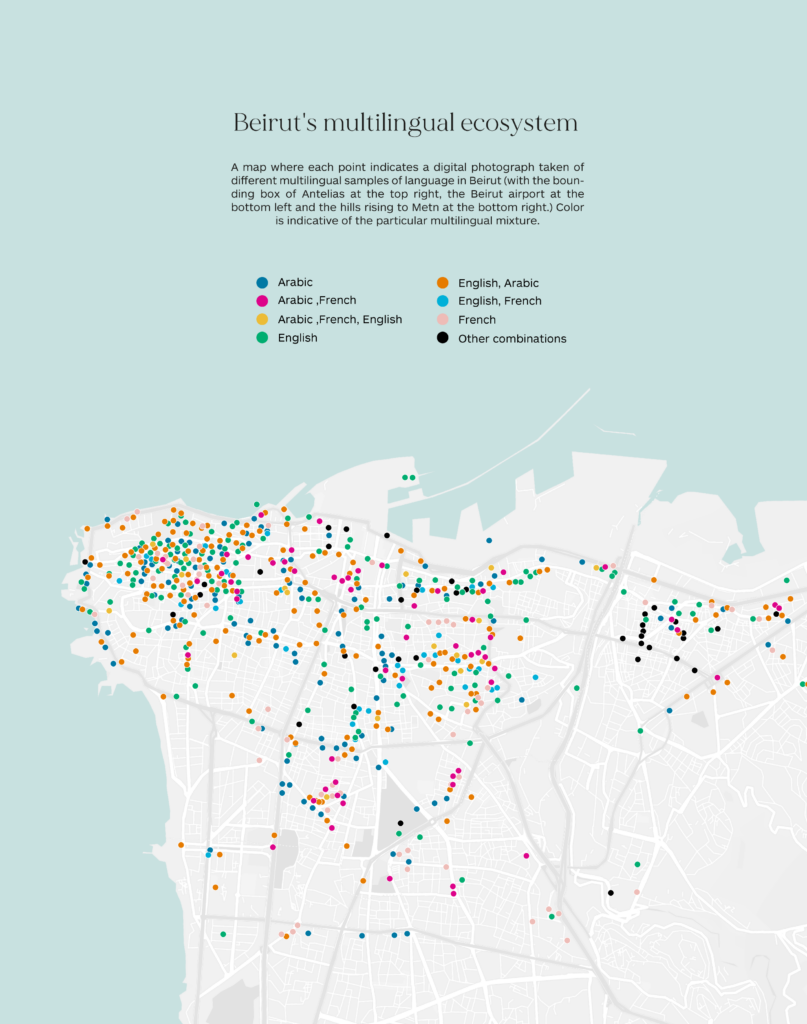

Pour tenter d’illustrer le paysage linguistique complexe de Beyrouth, une équipe de plus de 40 étudiants de l’Université américaine de Beyrouth a parcouru la ville en prenant en photo avec leurs smartphones les panneaux routiers, les stores des devantures des magasins, les affiches publicitaires, les graffitis, etc. La carte ci-dessous résume les résultats de cette recherche : une carte sur laquelle chaque point indique une photo numérique des différents échantillons multilingues trouvés dans la langue de Beyrouth. La couleur indique le mélange multilingue particulier en question.

La recherche confirme le fait que, tout au long de l’histoire, les villes multiculturelles ont eu plus de chances de survivre que les villes monoculturelles, ce qui démontre que l’écosystème multilingue photographié ici représente non pas un obstacle, mais une opportunité. Mais ce n’est pas tout : il se développe des projets créatifs qui utilisent le multilinguisme pour donner vie à de nouveaux concepts de design, en s’inspirant de la complexité linguistique tout en donnant une forme et une voix à une nouvelle forme de coexistence linguistique.

L’image montre une marque de design libanaise appelée Art 7ake (« Art des mots ») qui met en avant l’utilisation innovante des mots arabes représentés dans ses images combinées à du texte en anglais. À gauche, le mot arabe pour « thé » est « shay », qui se prononce de la même façon que le mot anglais « shy », d’où l’image d’un sachet de thé. Un tel design semblerait étrange pour un anglophone qui ne connaît pas le mot arabe pour « thé ». Dans l’image du milieu, le mot « mouse » signifie « loin » en arabe, ce qui explique l’image de la souris puisque « mouse » signifie « souris » en anglais. L’image de droite utilise le même concept d’illustration : « tore » en anglais (« déchiré » en français) signifie « bœuf » en arabe.

Arabic

بيروت: مدينة متعددة اللغات

يُعتبر لبنان، المعروف بنظامه التعليمي متعدد اللغات والتنقل عبر الحدود الوطنية لعدد سكانة الكبير المغتربين، موطناً لنظام بيئي لغوي مثير للاهتمام للغاية.

تعتبر اللغة العربية هي اللغة الرسمية، ويتحدث بها 88% من السكان.

تشير التقديرات إلى أن 20% من السكان يتحدثون الفرنسية في حياتهم اليومية، بينما يمكن لـ 65% من السكان قراءة اللغة الفرنسية والتحدث بها.

يتحدث 30% من السكان اللغة الإنجليزية، ولكن غالبيتهم قادرين على فهمها.

في شوارع المدن اللبنانية، اللغات الرئيسية التي ستسمعها هي الفرنسية والعربية والإنجليزية، وقد يحدث أيضاً أن تسمع بعض الإسبانية أو البرتغالية البرازيلية أو الألمانية أو الدنماركية. ما يميز لبنان عن أي بلد آخر متعدد اللغات هو أن الانتقال بين أكثر من لغة لا يقتصر على المحادثات المنطوقة – بل ينعكس أيضاً في اللغة المكتوبة.

في التسعينيات، أقرت الحكومة التدريس بثلاث لغات: العربية والفرنسية والإنكليزية. وقد وُصفت هذه اللغات رسمياً بأنها اللغة الأم الرسمية ولغتين أجنبيتين، واليوم تُقدّم جميعها تدريجياً كجزء من التعليم الابتدائي.

وهذا يعني أن اللغة الرئيسية المستخدمة في التعليم ليست اللغة العربية دائماً؛ وبدلاً من ذلك، تختلف من مدرسة إلى أخرى. وعلى وجه الخصوص، تختلف المدارس العامة والخاصة في هذا الصدد: ففي معظم المدارس الخاصة، تُستخدم اللغات الأجنبية (الفرنسية والإنكليزية) لتدريس مواضيع معينة تعتبر ذات أهمية خاصة، مثل العلوم والرياضيات. وعندما يتعلق الأمر بالرأي العام المحلي حول اللغة، يُنظر إلى اللغتين الإنكليزية والفرنسية عموماً على أنهما أكثر فائدة من اللغة العربية لدخول عالم العمل.

وعلى أي حال، فإن اللغات التي يستخدمها السكان المحليون أكثر من غيرها – كما هو الحال دائماً – غالباً ما تكون في نهاية المطاف هي اللغات المستخدمة في النظام التعليمي. ومن ثم، فإن اللغات المستخدمة في الأماكن العامة في بيروت، إلى جانب اللغة العربية، هي بشكل رئيسي الفرنسية والإنجليزية، مع عدد معين من اللغات الأخرى التي تستخدمها أقلية.

وهذا يعني أن اللبنانيين معتادين على قراءة نوعين مختلفين من الكتابة: النوع العربي، الذي يُكتب من اليمين إلى اليسار في أبجدية واحدة، والنوع الفرنسي والإنكليزي، الذي يُكتب من اليسار إلى اليمين في أبجدية أخرى. هناك أيضاً نظامان مختلفان للترقيم: الأرقام الغربية “العربية” التي نعرفها في الغرب (“0، 1، 2، 3 “) والأرقام الشرقية “العربية- الهندية (“٠، ١، ٢، ٣”).

وهكذا، في بيروت، في سياقات رسمية معينة مثل لافتات الطرق أو لوحات تعريف المباني العامة أو واجهات المعالم الأثرية، يمكننا العثور على الرسائل ذاتها بلغتين أو ثلاث لغات.

قد يعتقد المرء أن مزيج اللغات موجود للاستجابة لاحتياجات المناطق حيث توجد أعداد كبيرة من المقيمين الأجانب. ومع ذلك، بشكل عام، تضم البانوراما اللغوية في بيروت معرفة بالقراءة والكتابة متعدد اللغات والكتابة متعددة اللغات لأنها تعكس التركيبة السكانية متعددة اللغات التي تعيش هناك.

قد يبدو الأمر كأنه سيناريو لغوي فوضوي:

بعد كل شيء، من النادر جداً العثور على الرسالة ذاتها على لافتة عامة مكتوبة بثلاث لغات مختلفة، أو بالأحرى باستخدام مزيج من اللغات والأحرف. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن كتابة اللغة العربية بالحروف العربية وباستخدام الأبجدية اللاتينية.

عادةً ما تُكتب اللغات الغربية بالأبجدية اللاتينية، ولكن على لافتات الطرق القديمة (على الطرق الخلفية لشارع الحمرا، على سبيل المثال)، يمكننا العثور عليها مترجمة باستخدام الأبجدية العربية. قد تترافق العبارات المكتوبة بالأبجدية العربية بأي من نظامي الترقيم، ولكن عادة ما تُشاهد الكتابة باللغة الإنجليزية جنباً إلى جنب مع استخدام الأرقام الغربية “العربية”.

ومع ذلك، فإن الجانب المهم الذي يجب فهمه هنا ليس الفوضى، ولكن التوقعات الأساسية بأن الجميع في لبنان يتمتع بمستوى معين من الإلمام بالقراءة والكتابة باللغات العربية والفرنسية والإنجليزية. من الشائع جداً العثور على اللغات والنصوص وأنظمة الترقيم مستخدمة معاً بطريقة لا تكرر معنى الرسالة الرئيسية، ولكنها بدلاً من ذلك تكمله. يشير هذا التفصيل إلى حقيقة أن معرفة القراءة والكتابة في بيروت متعلقة بالسياق إلى حد كبير. ولذلك يُعد التنويع اللغوي متجذراً في سلسلة معقدة من القيم الثقافية التي تمنحها المجتمعات المحلية أولويات مختلفة بطرق مختلفة وفي أماكن مختلفة.

وفي محاولة لتوضيح المشهد اللغوي المعقد في بيروت، تجوّل فريق ضم أكثر من 40 طالباً من الجامعة الأمريكية في أرجاء مدينة بيروت والتقطوا بكاميرات هواتفهم الذكية صوراً لكل شيء، من لافتات الطرق ومظلات المتاجر إلى الملصقات الإعلانية والكتابات على الجدران. تلخص الخريطة أدناه نتائج هذا البحث: تشير كل نقطة على الخريطة إلى صورة رقمية لمختلف العينات متعددة اللغات الموجودة بلغة بيروت. يشير اللون إلى المزيج الخاص المعني متعدد اللغات.

تدعم البحوث حقيقة أن المدن المتعددة الثقافات قد حظيت، عبر التاريخ، بفرصة أكبر للبقاء على قيد الحياة من المدن الأحادية الثقافة، مما يدل على أن النظام الإيكولوجي متعدد اللغات المصور هنا لا يمثل عقبة بل فرصة. ولكن هناك المزيد: يتم أيضاً تطوير مشاريع إبداعية تستخدم التعدد اللغوي لإحياء مفاهيم التصميم الجديدة، مع أخذ الإلهام من التعقيد اللغوي وفي الوقت نفسه إعطاء شكل وصوت لشكل جديد من التعايش اللغوي.

تُظهر الصورة علامة تجارية لتصميم لبناني يسمى Art 7ake (‘Word Art’) ويعرض الاستخدام المبتكر للكلمات العربية المصورة في الصور جنباً إلى جنب مع النص الإنجليزي. على اليسار، الكلمة العربية لكلمة “tea” هي شاي، والتي تنطق بنفس لفظ الكلمة الإنجليزية “shy” (خجولة)، ومن ثم استُخدمت صورة كيس الشاي. سيبدو هذا التصميم غريباً بالنسبة لمتحدث إنجليزي لا يعرف الكلمة العربية “شاي”. في الصورة الوسطى، كلمة “mouse” تعني “فار” باللغة العربية، مما يفسر استخدام صورة الفأرة. تستخدم الصورة إلى اليمين المفهوم التصميمي نفسه: “tore” باللغة الإنجليزية تعني “تور” (ثور) باللغة العربية.

Bibliography

The Blurred Lines of Beirut’s Linguistics, Business”, Money 7f

Kaveh Waddell, “Mapping the Many Languages of Beirut”, Bloomberg, 2017

Photo credits: Marten Bjork, Unsplash